Art Is. . .

Art Is. . ., a joyful performance in Harlem’s African-American Day Parade, September 1983, was, from the point of view of the work’s connection with its audience, O’Grady’s most immediately successful piece. It’s impetus had been to answer the challenge of a non-artist acquaintance that “avant-garde art doesn’t have anything to do with black people.” O’Grady’s response was to put avant-garde art into the largest black space she could think of, the million-plus viewers of the parade, to prove her friend wrong. It was a risk, since there was no guarantee the move would actually work. As a black Boston Brahman cum Greenwich Village bohemian, with roots in West Indian carnival, for O’Grady the Harlem marching-band parade was alien territory. But the performance was undertaken in a spirit of elation which carried over on the day. Unlike the disappointment she’d felt with Mlle Bourgeoise Noire and The Black and White Show, this piece was to be about art, not about the art world. . . rather than an invasion, it was more a crashing of the party.

Although she had received a grant from the New York State Council on the Arts to do the piece, she decided not to broadcast it to the art world. She wanted to it to be a pure gesture, she told friends, in the style of Duchamps (whose work she had been teaching at SVA for several years). But this may also have been insulation against further frustration, a way to strengthen the sense of freedom.

The 9 x 15 ft. antique-styled gold frame mounted on the gold-skirted float moved slowly up Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard, framing everything it passed as art, and the 15 young actors and dancers dressed in white framed viewers with empty gold picture frames to shouts of “Frame me, make me art!” and “That’s right, that’s what art is, WE’re the art!” O’Grady’s decision was affirmed. With her mother Lena now in the later stages of Alzheimer’s, she would withdraw from the art world and not make art for the next five years.

Interview with Amanda Hunt, 2015

Amanda Hunt, “Art Is…: Interview with Lorraine O’Grady,” Studio: The Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine, pp 21-24, Summer/Fall 2015.

by Lorraine O’Grady with Amanda Hunt, Assistant Curator, Studio Museum in Harlem, 2015

Hunt, the curator of O’Grady’s solo exhibit of “Art Is…” at the SMH, discusses with her the images the artist still finds most intriguing, her process of gathering the images and more than a quarter of a century later organizing them into a new art work. Also touched on are the assembling of the performers and how they helped shape the piece.

****

In April 2015, Assistant Curator Amanda Hunt sat down with conceptual artist Lorraine O’Grady to discuss her 1983 performance Art Is…, the subject of this summer’s exhibition of photographs at the Studio Museum. For the performance, O’Grady and a group of fifteen men and women dressed in white rode up Seventh Avenue in Harlem on a float in the African-American Day Parade decorated with the words “Art Is…” O’Grady and her collaborators jumped on and off the float at different points during the procession, and held up gold picture frames of various sizes to onlookers of the parade. The performance, in effect, made portraits of the people and landscapes of Harlem. Art Is… raised a number of questions about representation and framing as it joyfully declared its local subjects “art.” More than three decades later, the Studio Museum presents the full series of photos documenting the performance to bring the work back to its local origins.

Amanda Hunt: Lorraine, we began talking about the photographic documentation of your performance Art Is…, and about the potential configuration of images we would present at the Studio Museum, and we came to something really interesting. You touched on the idea of the “greatest hits”— the images that people have been most drawn to in this series—and how over the course of more than thirty years, there are some more anomalous moments that have stuck with you for other reasons.

Lorraine O’Grady: I think that what I’m really talking about is the issue of ambiguity—a question of “What is it?” I mentioned to you that in one of the images there is a large apartment building caught in the large frame on the float that didn’t have any distinguishing aspects to it. People weren’t sitting out on the steps of the building the way they had been in other parts of the parade. There was a blankness to its architecture, so it was impossible to get a mental or emotional grip on it. There was something about not being able to imagine the life behind the blank windows, or even beyond the strange fluorescent lights in the long entrance leading to an inner courtyard—not being able to see anything, really. Whenever I look at that building, it still has this impenetrable mystery that fascinates me. And then there is the only vertical image in the series, the one I call Girl Pointing. It’s of a young girl, but now I find it’s hard to say exactly how old she was. As the frame approaches her, she points at it—she has this sort of smile on her face—and you can’t tell whether she is smiling at you or with you. You don’t know what she’s actually feeling. I can never settle on a feeling for her. (…)

re Art Is…, to Moira Roth, 2007

“Re: Art Is…, to Moira Roth.” Unpublished statement on Harlem parade performance. Based on email exchange with feminist art critic Moira Roth.

by Lorraine O’Grady and Moira Roth, unpublished, 2007

During an e-mail exchange in which they were sharing ideas and work, O’Grady sent Roth a copy of Lucy Lippard’s review of Art Is. . . . Roth’s questions prompted O’Grady to elaborate on the making and meaning of the performance.

****

. . . .

070429

Dear Moira,

I’m not surprised when people don’t know much about Art Is. . . I did it during my “Duchamp” years. At the time, I was teaching the Dadas and the Futurists at SVA and thinking of myself as a purist. Because the piece wasn’t addressed to the art world, I didn’t advertise it. I’ve changed a lot since then! The answers to your questions are fairly intertwined.

When I did the piece I was living in the West Village, in the same building I’d been living since arriving in New York via Chicago in ‘72. . . . I’m definitely a “downtown” type and had dreamt of being in the Village since I was 10 years old. When I was a teenager in the late 40s growing up in Boston, I would devour magazines with pictures of girls in long black skirts, black turtlenecks and black berets, drinking expresso and puffing on cigarettes in 4th Street cafes.

By late 1982, I’d been “out” as an artist for more than two years and had been invited by the Heresies collective, not to join the mother collective but to work on issue #13 of their journal, the one that was named “Racism Is the Issue.” The “issue” collective was a mixed group of artists and non-artists that included Ana Mendieta, Cindy Carr, Carole Gregory, Lucy and many others. It was a fractious group. One of the women in it was a black social worker whose name I don’t recall. I only remember that one evening at a meeting she said to me scathingly: “Avant-garde art doesn’t have anything to do with black people!” I didn’t know how to answer her, but I wanted to prove she was wrong.

Her comment stayed with me. But where would I find the “black people” to answer her? Perhaps because I am West Indian and a great believer in Carnival, the idea of putting avant-garde art into a parade came to me. But I knew instinctively that I couldn’t put it into the West Indian Day Parade in Brooklyn. There was so much real art in that parade it would drown out the avant-garde! So I decided on the African American Day Parade in Harlem, which was comparatively tame and commercial — you know, ooompa-ooompa marching bands and beer company adverts. My first idea was to mount several pieces on a parade float and just march it up 7th Avenue. But when I went to rent a flatbed from the company in New Jersey that supplies them, the owner told me: “You know, you have a maximum of three minutes, from the time a float comes into view on the horizon, stops-and-starts, then is out of sight at the other end.” That shook me. So I switched, from putting art into the parade to trying to create an art experience for the viewers. I asked the artists George Mingo and Richard DeGussi to help me. They built a 9 x 15 foot antique-styled, empty gold frame on the flatbed, which we covered with a gold metallic-paper skirt that had “Art Is. . . ” in big, black letters on both sides. Then I put an ad in Billboard and hired 15 gorgeous young black actors and dancers, male and female, dressed them in white, and gave them gold picture frames of various styles and told them to frame viewers along the parade route. They did this while hopping on and off the parade float, according to how fast it was moving or whether it was stalled.

The piece was done in 1983, with a grant from the NY State Council on the Arts, but as I said, it was done during my “Duchamp” years. Hahaha. I told the people at Just Above Midtown, the black avant-garde gallery I showed with, and the women in the Heresies racism collective knew about it, but almost noone else. The only person I gave slides to was Lucy Lippard, who was in both the Heresies mother and issue collectives and wrote about the piece five years later in Z. Lucy later printed two images in her book Mixed Blessings. But nothing else happened with that piece. I was shocked when, a few years ago, Johanna Drucker asked me for slides for a book she was writing. I thought noone had noticed.

It’s funny. The organizers of the parade were totally mystified by me and by the performance. The announcer made fun of the float as it passed the reviewing stand: “They tell me this is art, but you know the Studio Museum? I don’t understand that stuff.”

But the people on the parade route got it. Everywhere there were shouts of: “That’s right. That’s what art is. WE’re the art!” And, “Frame ME, make ME art!” It was amazing.

Lorraine

Email Q&A with Courtney Baker, 1998

Lorraine O’Grady Interview by Courtney Baker, Ph.D. candidate, Literature Program, Duke University.

Unpublished email exchange, 1998

The most comprehensive and focused interview of O’Grady to date, this Q & A by a Duke University doctoral candidate benefited from the slowness of the email format, the African American feminist scholar’s deep familiarity with O’Grady’s work, and their personal friendship.

****

( . . . ) Baker: As a set up, the two pieces I want to focus on are Mlle Bourgeoise Noire and Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline, mostly because there is more written on those pieces and I feel I have a better handle on them. Do you think this is okay, or am I remiss in leaving out some of your other performance work?

O’Grady: I understand why you’d know more about those two. Art Is. . ., the parade piece I did in Harlem, was intentionally less well known as I did it basically outside the art world.

( . . . )

This Will Have Been: My 1980s (ARTIS)

“This Will Have Been: My 1980s.” Art Journal 71, no. 2 (Summer 2012): 6-17.

© Lorraine O’Grady, 2012

Based on her lecture in conjunction with the exhibit This Will Have Been: Art, Love and Politics in the 1980s, the article puts several early works in historical context and explains O’Grady’s reverse trajectory from “post-black” to “black.”

****

( . . . ) Another Mlle Bourgeoise Noire event was Art Is . . ., a September 1983 performance in the Afro-American Day Parade in Harlem. A quarter-century later she would convert photodocuments of the performance into an installation, a selection of which is on view in This Will Have Been.

When she presented these events, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire would pin her own gloves—the gloves she’d lacked resolve enough to put into the gown—onto her chest as accessories. Perhaps she was getting stronger.

People often ask me to compare the live performance of Art Is . . . and the installation, but I can’t. They were incommensurate events. The day of the parade was hot, one of the hottest of the summer. There were a huge number of floats and marching bands, and they each had to wait on a side street before they could get en route. We shared the block with the Colt 45 group for almost four hours before our turn came. While we waited, the young actors and dancers I’d hired, none of whom may have known each other previously, began to bond. And some did more than that, I’m sure. It was that kind of day. We got onto the parade route about 1:00 p.m., and by the time we finished it was almost 6:00.

I’ve never had a more exhilarating and completely undigested experience in my life. The float was stop-and-stall, sometimes for fifteen minutes at a time. At other times, it would be moving so fast that in order to stay in line, you had to run like crazy, or just jump on and ride. I wasn’t from Harlem, so half the time I didn’t know what I was looking at. But I had deliberately not put the float into the West Indian Day parade in Brooklyn, where I would have felt at home, because I didn’t think avant-garde art could compete with real carnival art. I felt it might do better with the umpah-umpah marching bands and the beer company floats. The fact that I didn’t know what to expect is what made the performance a personal challenge and may have made it ultimately successful.

It was scary because I had no idea if it would work. But in the end, I think it met the challenge of the black social worker who’d told me in our Heresies issue collective, “Avant-garde art doesn’t have anything to do with black people!” There were more than a million people on the parade route, and time and time again we had confirmation that the majority of them understood that the piece, and their participation in it, was art. “Frame me! frame me! make me art!” we heard. And “That’s right! That’s what art is. We’re the art!” I was on a bigger high at the end of the parade than I can tell you. But at the same time, I couldn’t describe what my full experience had been.

There were hundreds of slides taken that day. In 2008, I took the images out of their storage box and made a time-based slideshow for my website using forty-three of them. But the sequentiality of the slideshow didn’t do it for me. A year later, for Art Basel Miami Beach, I reduced the slides to forty and made a wall installation, totally rearranging and mapping them. When I saw them like that—spatially, all over and at once—I felt I could finally intuit what the experience had been. But only what it had been for me.

Although it had been a joyous occasion, it wasn’t the joy that attracted me. It was the complexity, the mystery, the images that no matter how hard I looked would never become clear, would always remain out of reach.

The guy in one photo caught me the most. I could never have imagined him there. I made him the center of the installation. And the place in the next photograph! I could write a novel about what I can see and can’t see here. And the ambiguity of the gesture of a girl pointing. She is delightful, but is her response one of ironic complicity or is it dismissive? ( . . . )

Stedelijk Studies (AI), 2016

Stephanie Sparling Williams, “’Frame Me’: Speaking Out of Turn and Lorraine O’Grady’s Alien Avant-Garde.” Stedelijk Studies Issue #3: The Place of Performance. 13 pp. Academic journal of the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, 2016.

Eight years before the art world would become meaningfully integrated with the exhibits of David Hammons and Adrian Piper, and ten years before Coco Fusco and Gómez-Peña’s controversial performance Two Undiscovered Amerindians, American artist Lorraine O’Grady (born 1934 in Boston) staged a series of alien invasions on New York art spaces as the now notorious Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (Miss Black Middle-Class). The first time this persona appeared was at Just Above Midtown (JAM) during one of O’Grady’s first public performances in 1980. Dressed in an extravagant debutante-style gown made with one hundred and eighty pairs of white gloves, O’Grady shouted at her predominantly black audience as she ceremoniously whipped herself with a cat-o’-nine-tails spiked with white chrysanthemums:

THAT’S ENOUGH!

No more boot-licking…

No more ass-kissing…

No more buttering-up…

Of super-ass…imilates…

BLACK ART MUST TAKE MORE RISKS!!!

While the crashed gallery opening was for that of an exhibition called Outlaw Aesthetics, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire’s (MBN) invasion was unsolicited and her speech out of turn—a strategy scholar/artist Michele Wallace, argues is the only ‘tradition’ available to the black female critical voice.2 Later, art critic and curator Lucy Lippard invokes the powerful stance of speaking out of turn in her essay about Wallace’s work.3 Out of turn for Lippard can be understood as, “outside the dizzying circle of white and male discourse.”4 I recuperate the historical phrase “speaking out of turn” for this essay on Lorraine O’Grady’s performance art in order to revitalize and develop a vocabulary necessary for intervening in western-centric discourses of art history, the study of visual objects such as MBN, and for discussing the interventions these performative objects are making.

Speaking out of turn is predicated on a preexisting ‘turn,’ or order of speech. To speak out of turn means that you have spoken when it was not your turn to do so. More broadly defined, ‘speaking out of turn’ connotes 1) speaking at the wrong time or in an undesignated place, 2) saying something without authority, 3) making a remark/providing information that is tactless or indiscreet, or 4) speaking without permission.5 Speaking out of turn is a methodology developed out of the historical condition of being silenced and rendered invisible. Conditions, for example, established and maintained in order to manage the exclusive boundaries of the fine art world. (…)

Artspace, 2015

Karen Rosenberg, “How Lorraine O’Grady Transformed Harlem Into a Living Artwork in the ’80s—and Why It Couldn’t Be Done Today.” artspace.com, “In Focus.” July 22, 2015.

The 1983 African-American Day Parade, on Harlem’s 125 Street, included a rather unusual float—a gold-skirted vehicle topped by a giant, gilded picture frame. Atop it, 15 actors in all-white clothing danced with smaller frames; as the float moved along its route, they leapt out into the crowd and held them up to intrigued spectators, who summarily found themselves making art, or having art made of them.

This curious contribution to the parade was a project by the veteran conceptual artist Lorraine O’Grady, who now has a large critical and curatorial following but was then in the early stages of her career. She made the piece (which bore the wonderfully open-ended title of Art Is… ) with a grant from the New York State Council for the Arts and nothing in the way of publicity, at a time when documenting performance art was almost an afterthought and marketing it was a joke.

Art Is… was an experiment of sorts, contemporaneous with but less strident than O’Grady’s Mlle Bourgeoise Noire performances, in which she appeared in a kind of pageant-queen costume at gallery openings and exhorted fellow black artists to “take more risks.” But over time, and as the study of performance art has expanded, it has come to be known as one of her signature pieces—exhibited in such diverse contexts as Art Basel Miami Beach (2009), Prospect 2: New Orleans (2011-12), and the touring survey of ‘80s art “This Will Have Been” (2012).

Now the artwork has come home to the neighborhood where it took shape. This summer, for the first time, all 40 photographs from the performance are on view at the Studio Museum in Harlem (through October 25). There, viewers can spot vanished local landmarks like the Renaissance Ballroom and the Lickety Split Cocktail Lounge in the background of the parade pictures while contemplating the area’s ongoing transformation (the museum just announced plans to construct a new $122 million, David Adjaye designed building on its current site.)

In a conversation with Artspace deputy editor Karen Rosenberg, O’Grady spoke about the social and logistical challenges of making Art Is… , its evolution on the web and in recent exhibitions, and the reasons it could not be performed today. (…)

Jody B. Cutler, 2015

Jody B. Cutler, “Lorraine O’Grady’s Resonant ‘Happening’ Framed at SMH.” August 2, 2015.

This brief review by an art historian frames “Art Is…” as a “meta-art proposition” and draws interesting parallels to works by later black artists.

****

Good art accrues meanings through time, dragging along those seminal semiotics reflecting the circumstances in which it was created and the humanity of the artist behind it. That’s what we see in SMH’s current exhibition version of a happening (action; relational performance) conceived and enacted by artist-activist-intellectual-polymath-octogenarian, Lorraine O’Grady, with assistants, in 1983. On the cooperatively bright day of the annual African American Parade in Harlem, O’Grady and her team commanded a float of gilded, empty picture frames, and (physically) “framed” anonymous bystanders along the route–the photographic documentation of which is on view. The straightforward presentation and snap-snot quality of the images conveys an aesthetic for the work (qua work of art) that wrangles organization, excitement, and intellectual energy.

Literally moving whatever “art is . . .” out of the mainstream (downtown; white) art world and its partisan definitions (at that particular moment), O’Grady delivered a nuanced meta-art proposition as well as myriad messages and themes of invisibility and exclusion, and the social implications of interactive art, in the event of the piece and its aftermath, which lives on (not only here). Nari Ward, in his 2014 project, “Sugar Hill Smiles,” in which he “canned” reflected smiles of passers-by (in the Harlem neighborhood, Sugar Hill) to create conceptually individualized multiples, is heir (see Post). So are Kehinde Wiley‘s Baroque ish-framed portraits of anonymous African American youths.

The same O’Grady presentation was recently installed at P.S. 1 in the context of an international exhibition dealing with class and race politics and oppression (“Zero Tolerance“); it can withstand and well deserves the increasing exposure. Even stronger resonances are forthcoming at the history and heart of the piece, here on 125th St.

Hyperallergic, 2015

Louis Bury, “In and Out of Frame: Lorraine O’Grady’s ‘Art Is…’” Hyperallergic. September 5, 2015.

Bury’s lengthy and magisterial review is a model of intellectual attention to what is being seen — both inside and outside the frame. Beginning with the freedom of the piece’s title, it examines framing as form, content and metaphor, and illluminates police presence and the relation of viewer to viewed.

****

Like a Choose Your Own Adventure story or a game of Mad Libs, the elliptical title of Lorraine O’Grady’s 1983 performance piece, “Art Is…,” creates space, playful and inviting, for structured audience participation. You fill in the blank, the title says, in a demotic spirit, Art can be whatever you

want it to be. But ellipses do not simply, or even primarily, denote open space, a “to be continued” awaiting information; they also denote omission, something left out, perhaps suppressed. Both functions of the ellipsis — invitation and suppression — are at play throughout the piece, and I don’t mean “at play” metaphorically. O’Grady and her audience had a damned good time making art about something — African-American subjectivity — that is often missing from art. Their joy, thirty years on, is still infectious.

. . . . Questions about inclusion and exclusion are everywhere in “Art Is…,” thanks to the beautiful and uncanny emptiness of the many frames contained therein. Ordinarily, frames mark the disjunct between inside and outside, the line of difference between image and museum wall, family portrait and mantelpiece. But because the frames of “Art Is…” contain no actual pictures, what we can see inside of them is always coextensive with what we can see outside of them, and thus the borders between inside and outside come to seem arbitrary. This donut hole effect not only divides up the visual space of the photographs in unusual and compelling ways, giving them an off- balance, Winograndian whimsy, but it also means that there’s often as much going on outside the photograph’s internal frame as in it.

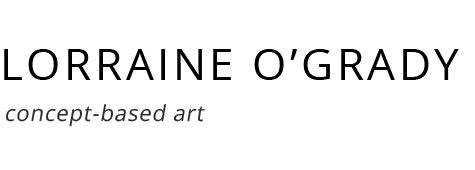

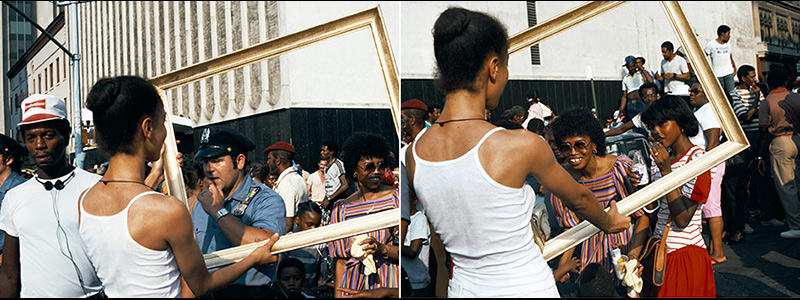

“Art Is… (Woman with Man and Cop Watching)” is representative in this regard. The center of the photograph consists of a performer holding up a small frame around herself and another woman; both their smiles are subdued, neutral. Outside that frame, behind and around the two women, is a panoply of expressive, in some cases troubling, men’s faces. From left to right: a black man with a quizzical eyebrow; a black man snarling in the direction of the picture frame; a black man in sunglasses, oblivious to the scene, staring off into the distance; a white cop, arms crossed, detachedly observing the women, his expression something between a snigger and a sneer. This multitude of mixed expressions, and not the face of the titular framed woman, is where most of the photo’s action actually takes place.

. . . . Of all the anomalies in the photographic series, of all the things that are outside the performative frame of parade conviviality, the subtle police presence is perhaps the most telling. Of course, the presence of police barricades indicates that the police aren’t, in one sense, anomalies at all: for better and for worse, they are part of the very structure and design of the parade and of the larger Harlem community (then as now). But within the visual universe of “Art Is…,” the police officers, all white, stand out for their discomfort as contextual minorities and, especially, by their role as strait-laced authority figures implicitly restraining the performative merry- making.

Four cops appear across the forty images; only one shares the spectators’ gaiety. In that lone image, “Art Is… (Framing Cop),” the framing dynamics are again complex and evocative. On the right, a woman performer stands in profile, facing center, with a tight-lipped and faintly mischievous smile, holding an empty frame close to her face. On the left, a male cop stands facing her, two or three feet away, hand relaxed on his hip, with an easygoing smile. Because the frame, too, is in profile, its empty interior is for once not visible to us; all we can see of the frame is its side. Though the performer, by holding the frame up to her own face, is the ostensible “canvas” here, with the cop as the viewer, her wide and searching eyes suggest, as the picture’s title implies, that she is the one doing the looking, and it is the cop who is on display. Her look puts the question to the cop, tests him: Do you really see me? Can you see that I can see you, too? It is not an easy question — far easier to flinch away or ignore it — but the cop’s naturalness, his obvious pleasure at her performance, suggests that he can indeed see her as a subject with her own agency and lifeblood and not just as an art object — or worse.

Artforum (AI), Summer 2012

Hannah Feldman, “This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s.” Artforum, in print Summer 2012.

Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago

This generally laudatory review of a groundbreaking exhibit on art of the 1980s features special attention on O’Grady’s piece in the exhibit, Art Is…, seen as encapsulating the problematic of curator Helen Molesworth’s strategy.

****

In September 1983 Lorraine O’Grady made good on a decades-old avant-garde bromide and brought art to the street. Or rather, she reframed the street as art – literally. For her work Art is…, O’Grady mounted an elaborately oversize golden frame atop a float set to proceed along Harlem’s Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard in the annual African American Day Parade. The caption ART IS…, handwritten on the skirt that wrapped around the base of the float, confirmed that the ever-shifting vistas of urban life and public spectatorship isolated by the frame were indeed “art.” Dancing around and alongside the float, a team of what O’Grady would later refer to as fifteen “gorgeous young black actors” redoubled this declarative gesture by holding similarly gilded frames up to the parade’s spectators, making them “art” too. In its original conception and execution, this was “art” for – and of – an emphatically non-art-world audience. Twenty-six years later, O’Grady reprised the work in a far more institutional context, assembling photographs of the various views that had issued from the 1983 parade and mounting them in a grid on the white wall of an art fair booth. This was how the piece appeared recently at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago’s “This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s,” where it brilliantly, and perhaps inadvertently, encapsulated both the promises and the problems of the 1980s art collected in the show.

Although Art Is… was hung in the section dedicated to the theme of “Democracy,” it might have been equally effective in any of the exhibition’s other sections: “Gender Trouble,” “Desire and Longing,” or “The End Is Near.” Indeed, curator Helen Molesworth’s gambit was to propose that the hundred-plus artists in the show were united by their collective debt to 1970s feminism, and in choosing these four themes as her points of entry into the ‘80s, she sought to highlight feminism’s diverse and interconnected legacies as they were parlayed into broader discourses about public belonging, identity, desire, and representation. In this fashion, one artist’s engagement with the ever-shifting problem of whom, exactly, constitutes a democratic public, or how those bodies otherwise excluded from such formulations might be properly imaged, were made to echo feminist claims regarding hierarchical inequality and inherited privilege.

The greatest strength of this curatorial strategy was its ability to build on and exceed the limits of individual works while also expanding the purview of what gets remembered in the historicist ambitions of periodization. For instance, the issues remarkably mobilized in O’Grady’s work were also shown to be present in Krzysztof Wodiczko’s game-changing Homeless Vehicle, Version 3, 1988, and Adrian Piper’s seminal My Calling (Cards #1 & #2, 1986-90, thereby sketching out a strikingly complex intertwining of seemingly disparate themes as they emerged throughout the decade. The effects of this contrapuntal setup were subtle but significant. Celebrated works were pried from the deadened shells of their usual reception and made to ask questions in new, often more multivalent ways than previously allowed. Arguments mounted in one section or on one wall reverberated with, complicated, and sometimes even undid arguments mounted elsewhere through a complex relay of transversal glances – both metaphoric and literal. ( . . . )

This will have been (AI), 2012

Jordan Troeller, “Lorraine O’Grady: Art Is…, 1983/2009.” In Helen Molesworth, This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago with Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2012, pp. 212-215.

Analysis of O’Grady’s 1983 Afro-American Day Parade, Harlem, performance Art Is…, in the groundbreaking exhibit This Will Have Been: Art, Love and Politics in the 1980s, curated by Helen Molesworth.

****

In September 1983, Harlem’s annual African American Day Parade, the self-proclaimed “largest black parade in America,” offered spectators its yearly carnivalesque celebration of African American music, customs, and history. It also contained a work of performance art. The proposition was simple: a float making its way along the route lacked the usual festive paraphernalia in comparison with the others. Atop its unadorned stage and simple gold-skirts base stood a single nine-by-fifteen-foot ornately carved frame, placed upright, so that, as the platform slowly moved by, the frame momentarily captured the activity around it: the passing building facades; the smiling upturned faces of the flanking spectators; and the bright-colored balloons, confetti, and costumes of the festival. A cadre of fifteen men and women bounced alongside it, each carrying their own, much smaller gold frame with which they approached children, adults, and police officers standing nearby, holding it up so that it too produced a multitude of living portraits. In bold lettering on the base of the platform, the words “ART IS” suggested that a more democratized version of art might be found, if only briefly, in the practices of ritualized daily life and in particular within the contingent and public character of the urban street.

Whether Lorraine O’Grady’s (American, born 1934) piece smuggled so-called high art into the realm of the popular, and whether the necessarily popular conditions of Art Is… (1983/2009) excluded it from the category of Art altogether is exactly the two provocations the work offers for consideration. In 1988, Lucy Lippard called Art Is “one of the most effectively Janus-faced works of the last few years.”1 By displacing art onto the street, the work flirts with its own potential illegibility within a museum context. Engaging questions long held dear by the avant-gardes of the early twentieth-century, Art Is inverts the terms of the Duchampian ready-made. Instead of questioning the extent to which the institutional conditions of exhibition determine the designation of an object (as Art or non-Art), O’Grady turns Duchamp’s challenge on its head and asks: To what degree can the public sphere—whose viability in the 1980s in New York was increasingly under pressure—sustain artistic production?

O’Grady situated this challenge within Harlem, a traditionally African American neighborhood identified with economic and racial marginalization in the postwar period, especially in the 1970s, when more than sixty percent of the buildings were abandoned or in severe disrepair. The African American Day Parade, established in 1968, emerged as an oppositional response to the economic and political marginalization of New York’s black communities, while also serving as a unifying event. By intervening in a space that signifies a gesture of solidarity, O’Grady transfers the avant-garde’s self-reflexive critique onto a popular form of artistic production whose role becomes one of consolidation rather than discord.

Art Is came on the heels of O’Grady’s better-known performance in the early eighties, in which she staged guerrilla-like interventions at the exhibition openings of New York art venues, such as the Just Above Midtown gallery and the New Museum of Contemporary Art. As if in drag, O’Grady would arrive as her alter ego, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (1980-83), dressed in an elegant gown comprised of hundreds of white gloves. Her elaborate costume evoked not only the ostentatious trappings of bourgeois wealth but also the white gloves that are part of a maid’s uniform, both of which alluded to metaphorical associations with the color white and racial “purity.” Performing a histrionic stereotype of the multi-inscribed black female subject, O’Grady foregrounded inequalities of class, race, and gender that otherwise went unacknowledged in such spaces, but were nonetheless constitutive of implicit claims made for art as a supposedly progressive liberal sphere. As compared to the provocation of the Mlle Bourgeoise Noire performances, Art Is’s attitude toward its public is conciliatory rather than confrontational. It attempts a more productive and generative relationship between object and viewer than that proffered by the gallery, wherein formal self-reflexivity obscures issues of inequality and allows the spectator to imagine herself to have transcended such concerns.

Pelican bomb (AI), 2011

Tori Bush, “Lorraine O’Grady, New Orleans African American Museum,” in “Round Up: The Best of Prospect.2: Part 1.” Pelican Bomb, November 9, 2011.

In the online magazine of the Contemporary Visual Arts Association of New Orleans, the writer says of Art Is… in Prospect.2 that the frame “not only asked ‘What is art?’ but also ‘Who chooses what is represented and how is it perceived'” by different audiences?

****

Lorraine O’Grady

New Orleans African American Museum

1418 Governor Nicholls Street

October 22, 2011 – January 29, 2012

“Avant garde art doesn’t have anything to do with black people.” This statement made by one of Lorraine O’Grady’s acquaintances was the impetus for the artist’s 1983 performance piece Art Is…, which empathetically proclaimed that avant-garde art is black people, black neighborhoods, black culture, and black issues. The photographic documents of this performance are now on view at the New Orleans African American Museum as part of the Prospect.2. They show O’Grady and 14 other African-American artists and dancers riding through Harlem’s African American Day Parade on a float resembling an ornate, gilded frame with bold black letters bearing the open-ended phrase “Art Is…” Participants on the float carried smaller frames, which they held up to audience members as they passed along Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard. O’Grady wrote years later in an email to art historian Moira Roth, “The people on the parade route go it. Everywhere there were shouts of: ‘That’s right. That’s what art is. We’re the art!’ And, ‘Frame ME, make ME art!’ It was amazing.”

A harbinger of identity politics in art, O’Grady’s use of the frame not only asked, “what is art?” but also, “Who chooses what is represented and how is it perceived by different viewers?” By putting black artists in charge of framing a predominantly black audience, the power of who makes art, who is art, and who perceives art is decided by the black community. In the history of western art, African Americans have been invariably depicted either as the other or not depicted at all. From the maid portrayed in Manet’s Olympia to the exclusion of black Abstract Expressionists from the famous photo of “The Irascibles” in 1950, the indelible lack of African Americans in the art historical canon is what gives credence to O’Grady’s performance. Years later, O’Grady would write, “[black bodies] function continues to be, by their chiaroscuro, to cast the difference of white men and white women into sharper relief.” By disallowing this fundamental contrast on that September day in Harlem, Art Is… redefined the relationship of African Americans both to and in art, allowing those present to celebrate themselves as works of art. ( . . . )

The Art Newspaper, 2009

Massimiliano Gioni, “Lorraine O’Grady, Art Is. . ., 1983/2009.” In “Expert Eye,” The Art Newspaper, Art Basel Miami Beach Weekend Edition (Day 4), p. 12, December 5-6, 2009.

A one-paragraph notice with photo in The Art Newspaper, the publication that carries the most clout at the fair. Points to ways in which O’Grady’s piece questions market values.

****

Expert eye Massimiliano Gioni, director of special exhibitions, New Museum, and artistic director, the Nicola Trussardi Foundation, Milan, picks… Lorraine O’Grady, Art Is…, 1983/2009

It’s a suite of photographs called Art Is… [at Alexander Gray, H27, full set of prints $40,000, edition of eight; individual prints $2,500-$4,000, edition of eight]. Lorraine O’ Grady is an artist who has recently been rediscovered and rightly so. This piece is a documentation of a parade that took place in Harlem in the 1980s and it consists of lots of photographs of people holding up gold frames. It’s an interesting piece to be seen in this context for two reasons, first of all because it reminds us of what’s not in the fair and of artists who usually remain excluded, like O’Grady. Secondly, it’s appropriate to see it in a fair because it is a place where people come to look at pictures, but also come to look at each other. In this performance the artist asked people to hold up frames and through this we reconnect with the art. There’s something about collective and spontaneous participation in the work that is quite interesting and we shouldn’t forget. We often think that art is about money or beauty, but art is basically what happens when people come together and that’s what this piece talks about. Interview by: Anny Shaw

Nick Mauss in Artforum (AI), 2009

Nick Mauss, “The Poem Will Resemble You: The Art of Lorraine O’Grady.” Artforum Magazine, vol. XLVII, no. 9, pp. 184-189, May 2009.

Mauss’s article for Artforum is, with Wilson’s INTAR catalogue essay, one of the most extended and authoritative pieces on O’Grady’s oeuvre to date. It was one-half of a two-article feature that also included O’Grady’s artist portfolio for The Black and White Show.

****

( … ) In September 1983, O’Grady initiated yet another invasion in the form of a float for Harlem’s African-American Day Parade. Conceived as an artwork expressly not for the art world, the float featured an enormous empty golden frame; its message was its title, spelled out in large block letters on the float’s base: ART IS… Framing the bright afternoon, building facades, spectators, street signs, birds, and balloons as it traveled the parade route, the float also carried a festive squad of men and women dressed in airy white, each carrying a golden frame of his or her own. Gamboling from the float into the street and toward the spectators, the performers danced through the crowd, holding up frames to mothers, gestures, policemen, accidental groupings, fleeting poses, children, exclamations, and clusters of friends, “framing” in close-up what the float itself only registered as the “big picture.” An intricate crisscross of art and activism, Art Is . . . spectacularizes O’Grady’s ongoing condition of being both part of and not part of, inside and outside, a society that relies on coeternal binary opposition. Simultaneously proposing to answer and question what avant-garde art has to do with lived experience, Art Is . . . frames life as a time-based medium. As in all of O’Grady’s work, the “political” is approached as a question of visibility and sensation. As Jacques Rancière has said of art: “It is political insofar as it frames not only works or monuments, but also a specific space-time sensorium, as this sensorium defines ways of being together or being apart, of being inside or outside, in front of or in the middle of, etc. It is political as its own practices shape forms of visibility that reframe the way in which practices, manners of being and modes of feeling and saying are interwoven.”

O’Grady’s work denies the impoverishment of art as a delimited zone, maintaining instead that it is contiguous with the real world. There is no escape ( . . . )

Judith Wilson (AI), 1991

Judith Wilson, Lorraine O’Grady—Critical Interventions, INTAR Gallery, New York, 1991.

Catalogue essay written for O’Grady’s first gallery solo exhibition, “Lorraine O’Grady,” INTAR Gallery, 420 W 42nd Street, New York City, January 21 – February 22, 1991.

****

( . . . ) Cultural Criticism

As an unpublished letter from O’Grady to the ( . . . ) editor of Art in America pointed out, [John Fekner’s Toxic Junkie mural] had been created, at her request, for the show as a means of “connecting the art inside the gallery with what was happening on the street.”

The latter preoccupation would be central to O’Grady’s next Mlle Bourgeoise Noire event. While working on an issue of the feminist art journal Heresies devoted to the question of racism she had been piqued by a Black woman poet’s assertion that “Black people don’t relate to avant-garde art.” With funds from the New York State Council on the Arts, O’Grady collaborated with artists George Mingo and Richard DeGussi in the creation of a float and accompanying performance for Harlem’s fall 1983 Afro-American Day Parade (illus. 6, 7).

Entitled Art Is . . ., the float consisted of a giant gilt frame mounted upright on a gold fabric-covered float bed, pulled by a pickup truck. The float’s title was inscribed on the side of this bed. Flanking the float, as it advanced, were teams of white garbed assistants who held smaller, empty frames up to the faces of some of the estimated half million or so on-lookers lining 125th Street. The piece was enthusiastically received by its audience, who offered spontaneous shouts of approval (“That’s right, that’s what art is! WE’re the art”) and competing pleas (“Frame me! Make ME art!”).

As O’Grady has noted, the parade format — with its ties to the rich array of Afro/Latino carnival traditions — is one that has particular cultural resonance for her as an African-American of West Indian descent. In exploiting this pop cultural mode, she “is one of the few artworld artists to have availed herself of such festive opportunities to escape ‘cultural confinement’ in the [artworld’s] ivory-walled towers,” critic Lucy Lippard has written. Here, for the first time, O’Grady extended her role as cultural critic to embrace the larger Black community, normally abandoned by both White and Black artists in their pursuit of esoteric aesthetic discourses.

The sense of triumphant generosity conveyed by the social breadth and exuberance of Art Is . . . (illus. 6, 7) probably reflects O’Grady’s having won two prestigious grants that year — a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship and a CAPS fellowship award. Despite these important affirmations of her talent, 1983 closed on a grim note for the artist, who learned in December that her mother was afflicted with Alzheimer’s Disease. Her artistic career came to a halt while she devoted the next four and a half years to her mother’s care.

ARTS Magazine, 1991

Gretchen Faust, “New York in Review,” Arts Magazine, vol. 65, no. 8, p. 98, April 1991.

A review of O’Grady’s first solo exhibit at INTAR Gallery, NYC, that focuses on her work in performance. Selected from Gretchen Faust’s column, “New York in Review,” ARTS Magazine, vol 65, no 8, April 1991, p 98.

****

It is always a little frustrating to write reviews in a short format, as it only allows one to touch on issues and highlight aspects of the work discussed. Though valuable, every once and awhile I come across a show that really demands more time and space consideration. The first solo show of Lorraine O’Grady’s photomontages (INTAR, January 21–February 22) is just such a show. O’Grady couples her wide-angle art awareness with a keen sociopolitical consciousness. The gallery is divided into four sections; each has a different “theme” relative to her two overall queries: What should we do? countered by What is there time for? As stated in the press release, the four rooms reflect, in order: 1) cultural criticism, 2) autobiography, 3) black female reclamation, and 4) work in and for the community. Each of the rooms contains photomontages exploring, through manipulated imagery, the assigned theme. Cultural criticism includes documentation of O’Grady’s best known and most acclaimed performance work, Mlle. Bourgeoise Noire. In this performance, O’Grady takes on an assumed and striking character, who dresses in a formal gown and cape fashioned from literally hundreds of white gloves. It is in this guise that O’Grady has appeared, unannounced and uninvited, at art openings as a virtual apparition/voice of conscience that “denounces Black artists’ political passivity in the face of curatorial and critical apartheid” and attacks “Black aesthetic timidity” (as stated in Judith Wilson’s catalogue essay, entitled Lorraine O’Grady: Critical Interventions). The second room explores autobiography and includes photographs documenting a metaphorical coming-of-age ritual/performance entitled Rivers: First Draft, involving several multi-racial players, which took place in Central Park in 1982. A compare-and-contrast collage that pairs images of the artist’s sister with those of Nefertiti is featured in the third room, and the fourth focuses on the documentation of a collaborative project, including the artists George Mingo and Richard DeGussi, which consisted of a large float, part of the 1983 Afro-American Day parade in Harlem. The float, Art is. . ., sported open gilt frames that were held out over the crowds, thus implying that anything caught within their boundaries was deemed art. In this piece O’Grady engages the relationship between contextualization and content in a joyous event, available and interesting to all. It is this ability to be direct and effective on a level that is both internally complex and essentially based in realism that distinguishes this work by an artist out on the bridge that seems to span the gap between art and life.

Gretchen Faust

April 1991

Lucy Lippard, 1988

Lucy R. Lippard, “Sniper’s Nest: ‘Art Is…'”, Z Magazine, p. 102, July/August 1988.

Highlighted box review, taking a retrospective look at O’Grady’s 1983 performance Art Is . . .. In “Sniper’s Nest,” Z Magazine, July-August 1988, p 102

****

One of the most effectively Janus-faced artworks of the last few years was Lorraine O’Grady’s float for the Afro-American Parade in Harlem. The title, “Art Is…” was emblazoned on the side of a huge, ornate, gold frame that rode on a float. The artist and a group of other women, dressed in white, hopped on and off the float as the parade progressed and held up smaller gold frames to children, cops, and other onlookers, making portraits of the local audience as the big frame made landscapes of the passing local environment.

The direct message of course was: Art is what you make it; Harlem and black people are as worthy as any other subjects for Art. On a more complex level, O’Grady was commenting on the artist as manipulator and reflector, and the participatory role of exchange in culturally democratic art. The piece was about “framing and being framed,” to borrow a phrase from corporate critic Hans Haacke. The initially simple idea opens up the field of art to include what has until now been peripheral vision, rarely projected on the centralized screens of galleries and museums.

O’Grady (who is black and has done performance pieces in the persona of Mademoiselle Black Bourgeoise) thus raises a layered set of questions about representation in high art. These questions were posed in the community and radiated to current analyses of stereotypes and representational exclusions in the mass and other media. The gold frame raises another set of questions about class, context, and autonomy. When photographically documented, the piece shows black women choosing their subjects, as well as a mutual exchange or collaboration, in which the artist or framers and their found subjects mutually determine the focus on the art, thus illustrating a process of self-determination sparked by an art process.

The piece can also translate effectively from its primary audience, Harlem residents, to a secondary one, the art world. The direct, intimate, photo booth process taking place within the parade as public drama allows the art to be both entertaining and affirming. The indirect process by which little recoding is needed for use in the “art world” opens up layers of meaning about the history of modernism and its constant search for the new, the history of collage and performance and site-specific art as potentially populist forms, and the one-liner as potential paragraph. And, finally, O’Grady’s piece scrutinizes the multiple meanings of the frame itself—physical (gold and theoretical (ways of seeing).