Mlle Bourgeoise Noire

Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, O’Grady’s first public performance, remains the artist’s best known work. The persona first appeared in 1980 under the Futurist dictum that art has the power to change the world and was in part created as a critique of the racial apartheid still prevailing in the mainstream art world.

Wearing a costume made of 180 pairs of white gloves from Manhattan thrift shops and carrying a white cat-o-nine-tails made of sail rope from a seaport store and studded with white chrysanthemums, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (Miss Black Middle-Class) 1955 was an equal-opportunity critic. She gave timid black artists and thoughtless white institutions each a “piece of her mind.” Her first invasion of an art opening unannounced was of Just Above Midtown, the black avant-garde gallery. Her second was of the recently opened New Museum of Contemporary Art.

But beyond her guerrilla invasions of art spaces, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire was a state of mind. Even when not in costume and when using her own name, the political aspect of O’Grady’s art would be under her inspiration for a four-year period. MBN “events” were surreptitiously indicated when O’Grady pinned white gloves to her clothing.

Though the performances were a “failure” — the art world would not become meaningfully integrated until the Adrian Piper and David Hammons exhibits of 1988-89 — Mlle Bourgeoise Noire had a mythic aftermath. Two images, of her beating herself with the whip and of her shouting the poem, were widely reproduced without an explanatory context, becoming empty signifiers that added to the mystification and misunderstanding surrounding the work. But then in the mid-90s, the costume was purchased by Peter and Eileen Norton. And finally, in 2007, it was positioned as an entry point to WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, the first-ever museum exhibit of the originating period of feminist art.

Brooklyn Rail, 2016

“Lorraine O’Grady, in Conversation with Jarrett Earnest.” Brooklyn Rail, pp. 56-63, print, February 3, 2016.

by Lorraine O’Grady in conversation with Jarrett Earnest, 2016

In this cover feature, her most important published interview to date, O’Grady discusses Flannery O’Connor as a philosopher of the margins, the archival website, working out emotions via Egyptian sculpture, Michael Jackson’s genius, and feminism as a plural noun.

****

Jarrett Earnest (Rail): A lot of your work relates to archives, both in content and form. When you started putting together your own website, were you thinking about it in terms of framing it as an archive?

Lorraine O’Grady: I did it because I thought I’d disappeared in many people’s minds—Connie Butler being one exception. Connie had been at WAC (Women’s Action Coalition) as a young woman, and I was one of the very few women of color who were active in that group. When she later curated the exhibition WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution (2007) and put me in it, I knew it would be important, I felt I had to be ready. That’s when I put the website up; I wanted to make it possible for anyone that was interested to become more engaged. Everything had disappeared from public view, it was all just sitting in the drawers of my file cabinets. I realized that for any of it to be understood I had to include everything: the images, the texts—it had to be a mini-archive. It’s designed to shape my work for the public and be a teaching tool. But it’s also meant as a staging for serious research, a start for access to my physical archives at Wellesley. I deliberately built the site to emphasize the connections between text and image—I didn’t want people to just look at the pictures. You can’t even get to the images without going through text; every link lands you back into text. During my exhibit at the Carpenter Center, I met with art historian Carrie Lambert-Beatty’s PhD seminar. I think I shocked the grad students when I said, “I would not be here now were it not for my website.” But you know, to have just appeared in WACK! with Mlle Bourgeoise Noire’s gown, I would have been a one-hit wonder. Having the website up with my other artwork and my writings available would make it more possible for me to be recuperated by a new generation of artists, writers, and curators.

Rail: One of the reasons your body of writing is so vital is that it really feels like it has a job to do, creating a context that wasn’t otherwise there.

O’Grady: Speaking was a demand that the work made on me, and that increasing interactions with others made on me. I learned so much each time I had to find a way to talk about the work.

( . . . )

This Will Have Been: My 1980s (MBN), 2012

“This Will Have Been: My 1980s.” Art Journal 71, no. 2 (Summer 2012): 6-17.

© Lorraine O’Grady, 2012

Based on her lecture in conjunction with the exhibit This Will Have Been: Art, Love and Politics in the 1980s, the article puts several early works in historical context and explains O’Grady’s reverse trajectory from “post-black” to “black.”

****

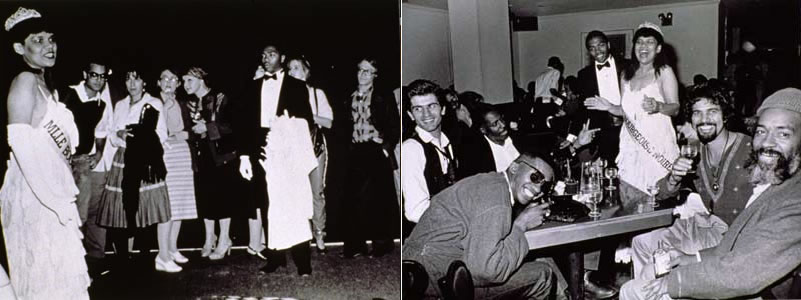

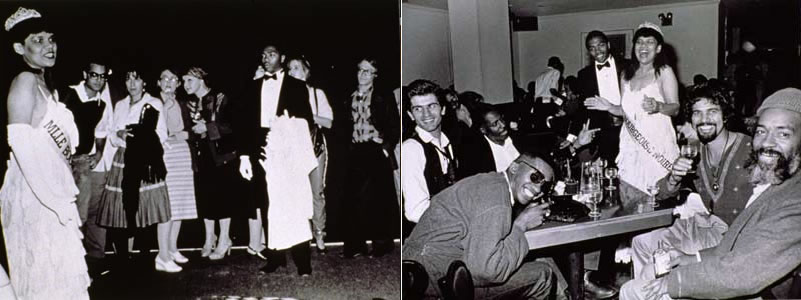

In 1980, after being transformed from post-black to black, I did my first public art work, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, for the opening of Outlaw Aesthetics at Just Above Midtown/Downtown. Figs. 4–5: WACK: Art and the Feminist Revolution, installation view, and Mlle Bourgeoise Noire . . . She was a persona who wore a gown and a cape made of 180 pairs of white gloves, gave away thirty-six white flowers, beat herself with a white cat-o-nine-tails, and shouted poems that criticized the mindsets of the white and the black art worlds. It was a hard performance, perhaps the most difficult I’ve done. I had to strip away everything that had been instilled in me at home and at school. Mlle Bourgeoise Noire wore a crown and a sash announcing the title she’d won in Cayenne, French Guiana, the other side of nowhere. (Black bourgeoise-ness was an international condition!) Her sash read “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire 1955.” That had been the year her class graduated from Wellesley. The performance was done in 1980, so it was a jubilee year, a year in which she would enact a new consciousness. Well, not entirely. At Wellesley, I’d worn white gloves myself and still had them in a drawer. But I didn’t include them in the gown. I couldn’t go that far. Figs. 6-11: Photodocuments of Mlle Bourgeoise Noire

After invading openings where she shouted poems against black caution in the face of an absolutely segregated art world, with punch lines like “Black art must take more risks!” and “Now is the time for an invasion!” Mlle Bourgeoise Noire became a sort of impresario. She presented events like The Black and White Show, which she curated at Kenkeleba, a black gallery in the East Village, in May 1983. Fig. 12–14: The Black and White Show, Kenkeleba installation view; Randy Williams; Jean Dupuy The exhibition featured twenty-eight artists, fourteen black and fourteen white, and all the work was in black-and-white. The curating and the work were subtle, but the intention was perhaps not. To a blindingly obvious situation, sometimes you make an obvious reply.

Another Mlle Bourgeoise Noire event was Art Is . . ., a September 1983 performance in the Afro-American Day Parade in Harlem. Fig. 15: Art Is . . . performance A quarter-century later she would convert photodocuments of the performance into an installation, a selection of which is on view in This Will Have Been.

When she presented these events, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire would pin her own gloves—the gloves she’d lacked resolve enough to put into the gown—onto her chest as accessories. Perhaps she was getting stronger. ( . . . )

Mlle Bourgeoise Noire and Feminism, 2007

“Comment for the WACK! Cell Phone Tour.”

© Lorraine O’Grady, 2007

For WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, the first-ever museum exhibit of feminist art, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in L.A., O’Grady was asked to record an audio statement for the cell-phone tour to explain how her piece related to the show’s theme.

****

Q: How does the work Mlle Bourgeoise Noire relate to art and the feminist revolution?

A: “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire” is French for Miss Black Bourgeoise. The back story I created for her was that she’d won the title in a worldwide event held in Cayenne, the capital of French Guiana. Cayenne may have been a backwater, but the black bourgeois condition was international! In 1955, the year she won her crown, all around the world, in London, Paris, Amsterdam, and Washington, DC, there were young women just like her.

MBN was a critical piece, located at the nexus of race, class, and gender. In 1980, when I created it, there were no role models in white feminist art for a tri-partite critique, or at least none that I was aware of. That era’s feminism seemed concerned exclusively with gender. Second-wave feminism was basically a white bourgeois construction that seemed to operate as though unconscious either that it was white or that it was middle-class. It was a time when white feminists could still believe that their definitions of sexual liberation and professional advancement applied identically to all women… and that they could speak for all women. In that era, even though black feminists may have admired the energy, even the delirium, of white feminist rhetoric, not to mention the bravery of many of its actions, they still felt alienated by and even a bit derisive toward it.

Still, the fact is, black feminism was itself a middle-class construction. But the middle-class it derived from was one in which women, however well-educated, did not have the luxury of a Betty Friedan-style feminine mystique. Even black Ivy League women married to doctors had to, or chose to, work. Since the end of slavery… given that blacks for the most part earned half of what whites did… middle-class lifestyles had been supported by families with two jobs. Black women were post-modernist avant la lettre.

It’s true that black bourgeois women worldwide were sexually repressed in this era. What else could they be when they were defined by their surrounding cultures as the universal prostitute? They were desperate for respect. In 1980, black avant-garde art, another middle-class construction, was equally repressed. THAT’s why Mlle Bourgeoise Noire covered herself in white gloves, a symbol of internal repression. THAT’s why she took up the whip-that-made-plantations-move, the sign of external oppression, and beat herself with it. Drop that lady-like mask! Forget that self-controlled abstract art! Stop trying to be acceptable so you’ll get an invitation to the party!

The key moment of MBN’s guerrilla invasions of art galleries was when she would throw down the whip and shout out her poems. They had punch lines like, on the one hand, “BLACK ART MUST TAKE MORE RISKS!” And on the other, “NOW IS THE TIME FOR AN INVASION!”

But Mlle Bourgeoise Noire was a kamikaze performance, really. In 1980-81, noone was listening. It wouldn’t be until 1988-89 that black artists were finally invited to the party… when Adrian Piper and David Hammons received their first mainstream exhibits. And a few years after that, second-wave feminism would start becoming third-wave. Oh, well.

Mlle Bourgeoise Noire and Feminism #2, 2007

“Mlle Bourgeoise Noire and Feminism 2”, Notes for MOCA Gallery Talk, March 22, 2007, ArtLies, #54, pp 48-49, Summer 2007.

© Lorraine O’Grady, 2007

As part of her gallery talk for WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution at MOCA, L.A., O’Grady read this statement inspired by Marsha Meskimmon’s important catalogue essay, in which the theoretical underpinning for the show’s historic statement of including 50% non-U.S. artists had been laid out.

****

Now that I have a captive audience. . . .

First, I want to thank Connie Butler, for her ability to SEE, to see that there was, and has always been more to art and to the feminist revolution than could be contained in the now canonical but limited Anglo-American-centric version of feminist history.

I also want to thank Marsha Meskimmon for her WACK! catalogue article, “Chronology through Cartography: Mapping 1970s Feminist Art Globally,” which opens the article section and provides the subsequent theoretical spine of the show. Personally, I think everyone should memorize this article so we can just move on. It’s a brilliant piece, and one from which I’ve gained many fresh insights into the historic fate of Mlle Bourgeoise Noire.

In my Walkthrough comments I’d complained that work like mine and Senga Nengudi’s had suffered from being misperceived through the imposition of a white feminist vocabulary that did not know it’s own name, a feminism which considered itself normative. . . equally valid for all women. . . and which did not recognize that it was in fact “white middle-class feminism” and that that was its name. A feminism that privileged gender over class and race and for which “revolution” often seemed to mean primarily “sexual liberation.”

But Marsha Meskimmon’s article has helped me understand more deeply what was really going on. Meskimmon quotes Doreen Massey as arguing:

“Most evidently, the standard version of the story of modernity—as a narrative of progress emanating from Europe—represents a discursive victory of time over space. That is to say that differences which are truly spatial are interpreted as bein diferences in temporal development—differences in the stage of progress reached. Spatial differences are reconvened as temporal sequence.”

Meskimmon adds: “The histories of feminist art practice are dogged by a similar, if more subtly tuned, dependency on temporal models masquerading as spatial awareness.”

She describes the chronological version of 1970s feminist art as implying “a cartography focused upon the United States and emanating outward from it—first toward the United Kingdom, as an ‘Anglo-American axis,’ then through Europe (white America’s cultural ‘home’) and [finally] touching upon the wider context of the Americas, Africa, and Asia…. [in] an implicit assumption that the ‘feminist revolution’ will come to us all, eventually.”

In this way, Meskimmon says, the chronological “timeline invitably justifies mainstream interpretations of feminist art by reading differences in terms of progress narratives. Where works differ significantly from the norm, they do not call the definitions of the center into question, but instead are cast as less advanced and ‘derivative’ or marginalized into invisibility as inexplicable unrelated phenomena—perhaps just not ‘feminist’ or not ‘art.'”

When I read that last sentence, I went “Yeessss! THAT must have been what happened!”( … )

Mlle Bourgeoise Noire 1980-81, Synopsis, 2007

“Mlle Bourgeoise Noire 1980-81, Performance Synopsis.” Unpublished text, plus 13 photos from the performance, posted to the L.A. Museum of Contemporary Art’s WACKsite, 2007.

© Lorraine O’Grady, 2007

O’Grady posted this brief synopsis of the performance and its background on the WACK! exhibit’s excellent website. She also posted 13 largely unknown photos-with-captions documenting the performance, which had become a victim to its two most well-known images. Lacking a full context, they had become empty signifiers.

****

Mlle Bourgeoise Noire first won her title in 1955. After 25 years of maintaining a lady-like silence, in 1980 she began invading art openings to give people a piece of her mind.

She wore a gown and cape made of 180 pairs of white gloves, 360 gloves in all. Here is a brief version of MBN’s “backstory,” taken from the signage for the Wadsworth Atheneum installation of the performance:

On the Silver Jubilee of her coronation in Cayenne, the capital of Guyane, MLLE BOURGEOISE NOIRE (Internationale), who could still fit into her coronation gown and cape of 360 white gloves, celebrated by invading the New York art world. During her anniversary tournée, she attended several openings unannounced: while all eyes were on her, she smiled, distributed four dozen white chrysanthemums and removed her cape. With the whip-that-made-plantations-move, she applied 100 lashes to her bare back, then shouted out an occasional poem.

The first time MBN invaded an art opening was at Just Above Midtown/Downtown, the black avant-garde gallery, in June 1980. JAM had just inaugurated a new space in Tribeca. The invasion was her response to the tame, well-behaved abstract art that had recently appeared in the “Afro American Abstraction” show at PS 1, an exhibit to which JAM had contributed a majority of artists.

The “occasional poem” she shouted at the JAM opening was:

THAT’S ENOUGH!

No more boot-licking…

No more ass-kissing…

No more buttering-up…

No more pos…turing

of super-ass..imilates…

BLACK ART MUST TAKE MORE RISKS!!!

Her next invasion was of the New Museum, at the opening of the “Persona” show in September 1981. The exhibit included nine artists using personas in their work. Mlle Bourgeoise Noire called it “The Nine White Personae Show.” When invited to give the outreach lectures to schoolkids for the show, she’d replied, “Let’s talk after the opening.”

The poem shouted on the occasion of the New Museum’s Persona opening was:

WAIT wait in your alternate/alternate spaces

spitted on fish hooks of hope

be polite wait to be discovered

be proud be independent

tongues cauterized at

openings no one attends

stay in your place

after all, art is

only for art’s sake

THAT’S ENOUGH don’t you know

sleeping beauty needs

more than a kiss to awake

now is the time for an INVASION!

After the opening, she was dis-invited from giving the outreach lectures to schoolkids.

Email Q & A w Courtney Baker (MBN), 1998

Lorraine O’Grady Interview by Courtney Baker, Ph.D. candidate, Literature Program, Duke University.

Unpublished email exchange, 1998

The most comprehensive and focused interview of O’Grady to date, this Q & A by a Duke University doctoral candidate benefited from the slowness of the email format, the African American feminist scholar’s deep familiarity with O’Grady’s work, and their personal friendship.

****

( . . . ) Q: Why did MBN have to speak? (This is kind of a simplistic question, but I think your response would be interesting.)

A: It’s not simplistic, of course, and it’s not something that I’ve really thought about before. MBN was crazy, wasn’t she? crazy and uncool. At the same time, and not contradictorily, she was avant and ultra-hip. The thing about MBN is that, for me, she’s the place where the theoretical becomes uncomfortably personal. ( . . . )

In 1980 when I first did MBN, the situation for black avant-garde art was unbelievably static. For most people, the concept of black avant-garde art was an oxymoron. Here was where you ran up against the baldest confusions and denials about black class—not just on the part of whites but of blacks too. Avant-garde art is made by and for a middle-class (and more occasionally, an upper class); it’s a product of visual training and refined intellectualization. So how could blacks fit into the equation? You have to remember that was still a time (mostly behind us now, thank God) of naiveté and unfluid definitions, where all blacks were assumed to be lower and under-class; and any who were not were considered to be inauthentic “oreos,” the expression used then. The saddest part was how confused black artists themselves were, how seemingly incapable of theorizing their situation. They believed in what they were doing, but at the same time they were afraid to present it for what it was. You had this weird spectacle of middle-class adult artists trying to pass as street kids. And always the pressure, that mainstream artists don’t have to feel, to be “relevant” to the “community,” whatever that is. No wonder the work and the artists themselves seemed stuck, waiting to be seen, to be recognized, to be let in. And no wonder, too, that so much of the work was cautious and fearful.

There was always hope, of course. Linda Bryant, the founder and director of JAM, had lost her space on 57th Street. After a year in limbo, she’d relocated to Franklin Street in Tribeca. The new gallery was down the street from Franklin Furnace, around the corner from Artists Space, and a few blocks up from Creative Time: Tribeca was alternative space central.

I wasn’t aware of all that, though. I just knew that JAM had provided most of the artists for the Afro-American Abstraction show at PS 1, so I signed on as a volunteer. I wanted to be near those people. While others renovated the space, did the floors, raised the walls, etc., I worked on publicity. One phone call I made was to the New Yorker, to see if they would list the space’s opening show, Outlaw Aesthetics. They had not listed JAM previously. I’ll never forget the sarcasm in the voice of the woman who answered the phone.

She said: “She always puts titles on her shows, doesn’t she?” Not good, I thought to myself. But I didn’t tell Linda. The opening of the Outlaw Aesthetics show was when Mlle Bourgeoise Noire appeared for the first time.

I’d naively thought her response was just New Yorker snobbishness. Later I realized that the dismissive attitude was everywhere. MBN appeared at the New Museum in September 1981. That November, ARTnews Magazine had an 11-page article entitled “New Faces in Alternative Spaces.” The pages were chock-full of photos and discussions of PS 1, Franklin Furnace, Artists Space, the Kitchen, the New Museum, and others. But not a single mention of Linda Bryant, JAM, or of any of the artists (David Hammons, Senga Nengudi, Howardena Pindell, Maren Hassenger, Houston Conwill, Al Loving, Randy Williams, Fred Wilson, etc., etc.) who’d showed there. Not one line. Not even in passing. In spite of all the work Linda had done in helping to found the Downtown Consortium of alternate art spaces. In spite of her organizing and hosting the Dialogue exhibition and performance series, for which Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline was created.

Whatever hole black avant-garde (middle-class) art had fallen into, it was still there. And it would stay there until the season of 1988-89, when just as arbitrarily it would emerge, brought to light by the needs of the white art world.

MBN tried again, in 1983; not with a gown and a shouted-out poem, but this time by curating The Black and White Show at Kenkeleba. It was another shout that disappeared without being heard. ( … )

Interview by Linda Montano (MBN), 1986

Interview. In Linda Montano, Performance Artists Talking in the Eighties: Sex, Food, Money/Fame, Ritual/Death, University of California Press, Berkeley. Based on 1986 interview.

June 1986*

Montano’s questions on “ritual” for Performance Artists Talking cast interesting light on the connection between O’Grady’s early life and her performances. The unedited transcript of the interview contains answers in greater depth on Mlle Bourgeoise Noire and Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline.

****

Montano: What were your childhood rituals?

O’Grady: ( . . . ) By late adolescence, the rituals had less to do with things like family and church and more to do with the outside world. At sixteen there was the birthday party. I didn’t want a birthday party. I wanted a formal sit-down dinner. At seventeen there was the cotillion. The two most prestigious black social clubs each sponsored an annual cotillion, and both invited me, but by that time, my passion of rejecting the usual rituals was already established. I seemed to be the only girl from that social set who didn’t come out that year. A year later at college, the expected bids to join the two nationwide black sororities, Alpha Kappa Alpha and Delta Sigma Theta, came in. Even though my sister had been president of the Boston chapter of Alpha Kappa Alpha, and everyone assumed I would go AKA, I didn’t. I refused to have anything to do with that sort of thing. The irony is, here I’d refused the cotillion, refused the sorority, but when I created Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, a satirical international beauty pageant winner with a gown and cape made of one hundred eighty pairs of white gloves, she was described by critics as a debutante. I guess I was doing those rituals in my own way in my art later on, but distanced, as anti-rituals. They have nothing to do with nostalgia or an acknowledged longing but are more critical modes of attack than of participation. But who knows? They could be a longing that doesn’t know its own name!

Montano: Did you go through a traditional art school education before this character emerged?

O’Grady: I’d had an exceptionally traditional and elitist education, which I had to work hard to rid myself of in order to become an artist. ( . . . )

About twelve years ago I left a second marriage and came to New York as the girlfriend of a big-time rock music exec. In order not to be just his girlfriend, I began writing rock criticism and feature articles, first for the Village Voice and then for Rolling Stone. I guess you could say I had a meteoric career. ( . . . )

Then my life completely changed. A friend of mine was teaching at the School of Visual Arts and [asked me to teach there. It was a total crash immersion into the world of art. Several years later] I went to the opening of an exhibit at P.S. 1 called African American Abstraction. I’d seen it advertised in the newspaper, and it interested me. When I got there I was blown away. The galleries and corridors were filled with black people who all looked like me, people who were interested in advanced art, whose faces reflected a kind of awareness that excited me. For the first half hour of the opening I was overwhelmed by the possibilities of a quality of companionship I hadn’t imagined existed. But then I settled down intellectually and became quite critical. By the time I left, I was disappointed because I felt the art on exhibit, as opposed to the people, had been too cautious—that it had been art with white gloves on.

I went down to Just Above Midtown [where many of the artists who’d been at P.S. 1 showed, and worked as a volunteer helping to open their new space. I began associating with those artists and making friends.] I wanted to tell them what I’d felt, but in an artistic way. One afternoon, on my way from SVA to JAM, I was walking across Union Square. That was before the square had been urban-renewed; it was still incredibly filthy and druggy. As I entered the park—perhaps to get away from its horrible reality—a vision came to me. I saw myself completely covered in white gloves. That’s how my persona Mlle Bourgeoise Noire was born. It was a total vision, and by the time I emerged from the park, three blocks later, it was complete. The only element I added after that was her white whip. I understood that the gloves were a symbol of internalized oppression, but knew I needed a symbol of the external oppression, which was equally real. The whip came that evening when I got home. ( . . . )

Stedelijk Studies (MBN), 2016

Stephanie Sparling Williams, “’Frame Me’: Speaking Out of Turn and Lorraine O’Grady’s Alien Avant-Garde.” Stedelijk Studies Issue #3: The Place of Performance. 13 pp. Academic journal of the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, 2016.

Eight years before the art world would become meaningfully integrated with the exhibits of David Hammons and Adrian Piper, and ten years before Coco Fusco and Gómez-Peña’s controversial performance Two Undiscovered Amerindians, American artist Lorraine O’Grady (born 1934 in Boston) staged a series of alien invasions on New York art spaces as the now notorious Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (Miss Black Middle-Class). The first time this persona appeared was at Just Above Midtown (JAM) during one of O’Grady’s first public performances in 1980. Dressed in an extravagant debutante-style gown made with one hundred and eighty pairs of white gloves, O’Grady shouted at her predominantly black audience as she ceremoniously whipped herself with a cat-o’-nine-tails spiked with white chrysanthemums:

THAT’S ENOUGH!

No more boot-licking…

No more ass-kissing…

No more buttering-up…

Of super-ass…imilates…

BLACK ART MUST TAKE MORE RISKS!!!

While the crashed gallery opening was for that of an exhibition called Outlaw Aesthetics, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire’s (MBN) invasion was unsolicited and her speech out of turn—a strategy scholar/artist Michele Wallace, argues is the only ‘tradition’ available to the black female critical voice.2 Later, art critic and curator Lucy Lippard invokes the powerful stance of speaking out of turn in her essay about Wallace’s work.3 Out of turn for Lippard can be understood as, “outside the dizzying circle of white and male discourse.”4 I recuperate the historical phrase “speaking out of turn” for this essay on Lorraine O’Grady’s performance art in order to revitalize and develop a vocabulary necessary for intervening in western-centric discourses of art history, the study of visual objects such as MBN, and for discussing the interventions these performative objects are making.

Speaking out of turn is predicated on a preexisting ‘turn,’ or order of speech. To speak out of turn means that you have spoken when it was not your turn to do so. More broadly defined, ‘speaking out of turn’ connotes 1) speaking at the wrong time or in an undesignated place, 2) saying something without authority, 3) making a remark/providing information that is tactless or indiscreet, or 4) speaking without permission.5 Speaking out of turn is a methodology developed out of the historical condition of being silenced and rendered invisible. Conditions, for example, established and maintained in order to manage the exclusive boundaries of the fine art world. (…)

Hyperallergic, 2013

Alexis Clements, “Animating the Archive: Black Performance Art’s Radical Presence.” Hyperallergic.com, Oct 10, 2013.

Documenting performance art has always been tricky. There have been tons of panels and talks in the past year or two about the challenges and benefits of different methods of archiving. Martha Wilson, founder of Franklin Furnace, is developing a searchable database of work that her organization has hosted or supported over the years. The Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics has mounted a free online digital video library that allows viewers to see a wide range of work by artists from across the Americas. And the recent re.act.feminism project brought together new performance with re-performance of old works, a web-based archive, exhibits of documentation and ephemera, and lectures.

But many of the issues surrounding documentation and re-performance boil down to one simple fact: there’s no way to fully capture what it feels like to be there during the original performance. Not only is it impossible to capture things like the smell or psychic energy flowing between a performer and their audience, you can’t re-create the political and social milieu in which the work was made.

For this reason, one of pieces that struck me right off the bat when I entered the exhibition Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery was Lorraine O’Grady’s “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire” (1980–83). In the gallery, the work is represented by a series of 12 black-and-white photographs from her 1981 performance “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire goes to the New Museum.” What makes the images so striking is not just O’Grady’s use of the iconography of the beauty queen, with her broad smile and long gown (in this case made entirely of white gloves purchased from thrift stores), but also the fact that you can see the reactions of people witnessing the performance. You can begin to read things like confusion, curiosity, discomfort, amusement, and distance in their facial expressions and body language.

According to O’Grady’s website, these performances were intended as invasions of established art institutions — both the many spaces that were exhibiting work exclusively by white artists and black art spaces like Just Above Midtown. Given her use of surprise and confrontation, the photos offer tiny glimpses of the effect that she might have been having on unsuspecting partygoers, whipping herself and shouting through glossy lipstick: “WAIT wait in your alternate / alternate spaces / spitted on fish hooks of hope / be polite wait to be discovered … THAT’S ENOUGH don’t you know / sleeping beauty needs / more than a kiss to awake / now is the time for an INVASION!” (…)

Nick Mauss in Artforum (MBN), 2009

Nick Mauss, “The Poem Will Resemble You: The Art of Lorraine O’Grady.” Artforum Magazine, vol. XLVII, no. 9, pp. 184-189, May 2009.

Mauss’s article for Artforum is, with Wilson’s INTAR catalogue essay, one of the most extended and authoritative pieces on O’Grady’s oeuvre to date. It was one-half of a two-article feature that also included O’Grady’s artist portfolio for The Black and White Show.

****

( . . . ) O’Grady, who first gained visibility in the art world in the early 1980s through her invasions of openings at venues such as the then-new New Museum and the black avant-garde gallery Just Above Midtown, insisted that there could be a complex subjectivity outside “whiteness” and “blackness.” In Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, 1980-83, O’Grady embodied her alter ego, a debutante from Cayenne, French Guiana, dressed in a cape and gown made from 180 pairs of debutante’s white gloves. She carried a cat-o’-nine-tails spiked with chrysanthemums and whipped herself while shouting vituperative poems. At Just Above Midtown, she railed:

THAT’S ENOUGH!

No more boot-licking . . .

No more ass-kissing . . .

No more buttering-up . . .

No more pos . . . turing

of super-ass . . . imilates . . .

BLACK ART MUST TAKE MORE RISKS!!!

And at the New Museum, she jeered:

WAIT

wait in your alternate/alternate spaces

spitted on fish hooks of hope [. . .]

THAT’S ENOUGH don’t you know

sleeping beauty needs

more than a kiss to awake

now is the time for an INVASION!

Within the safe zones of these restricted communities, “Miss Black Middle Class” inserted hybridity and disagreement into social situations that were meant to protect and continue the production of consensus. By now, this performance is justifiably iconic and has become O’Grady’s best-known artwork. It is also her most aggressive, but its subtleties and symbolic opulence can easily be drowned out by overemphasizing its badass attitude. Even though it appeared to have emerged out of nowhere, it has a long but decidedly not art-historical genesis.

( . . . )

art Das Kunstmagazin, Berlin, 2008(9)

Kito Nedo, “Re.Act.Feminism – Eine Kiste für Brüste und Protest”. art Das Kunstmagazin (art-magazin.de), p. 87, Print: no. 1, Akademie der Künste, Berlin, 2009.

Review of feminist art show with 25 artists in exhibition, plus 80 in video archive, makes special mention of O’Grady and three other artists, including Valie Export, Yoko Ono, and Gabrielle Stötzer.

****

Photo: Kate Gilmore, “Star Bright, Star Might”, 2007, video still of face in box (Courtesy Smith-Stewart Gallery)

A BOX FOR BREASTS AND PROTEST

Does the Berlin show “Re.act.feminism” at the Academy of Arts succeed as a witty refutation of the male-dominated art establishment? Kito Nedo reports on a survey of female performance art and promising new discoveries.

“Art has no sex…,” wrote the American art critic Lucy Lippard in the mid-1970s and, sure enough, she did not forget to add: “That’s all very well, but artists do.” Lippard’s text, which criticized the male-dominated art establishment, was published on the occasion of an exhibition of the Austrian Valie Export, whose work inspired an entire generation of young female artists to create feminist art, above all performances—an achievement comparable perhaps only with the work of Yoko Ono. For example, with Export’s “Tap and Touch Cinema” (1968), a strapped-on box within which passers-by could touch the breasts of its wearer, the artist put her body in the service of art in accordance with the radical spirit of the time.

When the Berlin Academy of Arts presents a focused examination of feminist performance art from the sixties and seventies then Valie Export is certainly included. Beyond the presentation of already well-known artists, however, curators Bettina Knaup and Beatrice E. Stammer hope to broaden the perspective and to document the manifold approaches taken by extremely diverse activists in the USA and Eastern and Western Europe. Therefore, amongst the documentation and works of circa 25 artists, one also finds lesser-known names such as that of Lorraine O’Grady, who protested as “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire” in the New York of the 1980s against the under-representation and self-denial of African-American artists, while at the same time reinforcing the view that art can change the world.

Even the Berlin wall could not stop the offshoots of the feminist avant-garde. Deep in the province of the German Democratic Republic, under the suspicious eye of the Stasi (East German Secret Police), artist Gabriele Stötzer and others founded “Exterra XX,” the first and only independent collective of female artists that showed film and photography in addition to performances. ( . . . )

Download full PDF

The New York Times, 2007

Holland Cotter, “The Art of Feminism as It First Took Shape,” WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, at the Museum of Contemporary Art, LA. New York Times, March 9, 2007.

Opening of the first-ever museum show of feminist art at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Holland Cotter’s feature-length review was illustrated by four works, including Mlle Bourgeoise Noire.

Friday, March 9, The New York Times

****

LOS ANGELES, March 4 — If you’ve held your breath for 40 years waiting for something to happen, your feelings can’t help being mixed when it finally does: “At last!” but also “Not enough.” That’s bound to be one reaction to “Wack! Art and the Feminist Revolution” at the Museum of Contemporary Art here, the first major museum show of early feminist work. ( . . . )

One thing is certain: Feminist art, which emerged in the 1960s with the women’s movement, is the formative art of the last four decades. Scan the most innovative work, by both men and women, done during that time, and you’ll find feminism’s activist, expansionist, pluralistic trace. Without it identity-based art, crafts-derived art, performance art and much political art would not exist in the form it does, if it existed at all. Much of what we call postmodern art has feminist art at its source. ( . . . )

Gradually but always incompletely, boundaries loosened up. In the early ’70s, with the Vietnam War in progress, women could see their oppression as part of a larger oppression. At the same time, in different forms, with different priorities, feminism, often assumed to be a Western phenomenon, was developing in truly radical ways in Africa, Asia, South America. There never was a Feminism; there were only feminisms.

How does any show lay out this multitrack panorama? One way to start is by abandoning linear chronology, which is what “Wack!” does, though this doesn’t mean it escapes accepted models of history. The presence of figures like Eleanor Antin, Louise Bourgeois, Mary Beth Edelson, Eva Hesse, Mary Kelly, Adrian Piper, Miriam Schapiro, Carolee Schneemann and Hannah Wilke adds up to a pantheon of textbook heroes — a market-ready canon of exactly the kind early feminism tried to disrupt.

(. . . ) Some of the most radical work of all, though, is in video and in the related medium of performance. And no combination of the two is more mesmerizing than “Mitchell’s Death” (1978) by Linda M. Montano, in which the artist, her face bristling with acupuncture needles, delivers an account of her husband’s violent end in the rhythms of Gregorian chant [see photo].

Another video is hard to shake in a different way. In the 1975 “Free, White and 21,” Howardena Pindell plays the roles of a black woman talking about art-world racism and a white woman accusing her of paranoia. A glance at the show suggests how on the money Ms Pindell’s polemic was. Along with Ms. Nengudi, Faith Ringgold, Betye Saar, the filmmaker Camille Billops and the wonderful conceptualist Lorraine O’Grady are the only African-American artists who have work in the show, with the collective called “Where We At” Black Women Artists present only in photographs.

The collective, which stayed together from 1971 to 1997, had a fascinating history, though you learn nothing about that in an exhibition that is frustratingly bare of wall labels. (A cellphone tour offered by the museum covers only certain entries, and is short on hard information.)

The fastidious art-speaks-for-itself approach is O.K. for a Brice Marden retrospective, but in a content-intensive historical show with a hefty amount of unfamiliar material it does a disservice to art and audience alike. Without some context, there is simply no way to understand the extraordinary career of Suzanne Lacy, one of the few artists — Ms. O’Grady is another — who deals directly and pointedly with issues of women and class [see photo of Ms. O’Grady’s Mlle Bourgeoise Noire]. Nor it is possible to make sense of what’s going on in a 1977 performance by the Lesbian Art Project, presented as a silent and unannotated slide show.

Fortunately, work by other lesbian artists is far more accessible and, in the case of short films by Barbara Hammer, sexually explicit, loaded with attitude and hilarious. The show’s lesbian artists — among them Ms. Fishman, Ms. Hammond, Tee Corinne (1943-2006) and Nancy Grossman — represent a version of feminism that has particular pertinence today. With their insistence on experiencing gender — along, one must hope, with race and class — as an unfixed category, but one they control, and their interest in playing with various versions of “great,” they are exercising freedoms of choice that feminism always offered: freedom to challenge received truths, to exchange passivity for activism, to find solidarity in diversity, to adopt ambiguity and ambivalence as social and aesthetic strategies. And by doing so, they are acknowledging that the art they are making, whatever form it takes, is political by default ( … )

Cady Noland, 2002

Cady Noland, “Artists Curate: Back at You,” Artforum Magazine, vol. XL, no. 5, pp. 106-111, Jan 2002.

“THEY ARE CONFRONTATIONAL, TOUGH,” says Cady Noland about the artists she brings together [in this portfolio]. “WHUT CHOO LOOKIN AT, MOFO?” asks Adrian Piper’s alter ego in Self Portrait as a Nice White Lady, 1995. It’s a question of who’s welcome, who’s allowed in and who’s not. It’s a question of “hosts” and “guests.” The viewer may not be the only one who feels uneasy—the artists themselves take considerable risks. Chris Burden’s early performances, for example, posed obvious dangers to the artist— aesthetic, physical, and moral. Willing to break a “‘fourth wall”—in Burden’s case, his own skin—these artists are also keen “to get the last word,” Noland says. Burden’s collages consist of reviews of his work bearing the artist’s marginalia. He’s shooting back—even, as Noland puts it, at the risk of “shooting himself in the foot.”

. . . Like Burden and Piper, Lorraine O’Grady operates at the edges of performance art, “defining its tense and bitter borders.” Breaking the fourth wall rids us of all sense of fiction. In the course of O’Grady’s disruptions—crashing an opening, for instance—she would spit out poems about art and race. “This work reclaims dignity at the cost of making the artist so difficult as to court the possibility even the probability, that she’ll be ignored altogether,” Noland observes. “The irony is that dignity can be reclaimed through such non-decorous means.” (…)

Andrea Miller-Keller (MBN), 1995

Andrea Miller-Keller, “Lorraine O’Grady: The Space Between,” in Lorraine O’Grady / MATRIX 127,” Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford CT, pp. 2-7, 1995.

Brochure article written for the one-person exhibit “Lorraine O’Grady / MATRIX 127,” The Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT, May 21 – Aug 20, 1995.

****

( . . . ) For O’Grady, her own multi-racial, upper-middle-class background has been both a source of displacement and empowerment. Her culturally-complex childhood often left her feeling that she “belonged everywhere at once and nowhere at once.” But, from these same circumstances she learned to negotiate skillfully a range of social, racial, and class milieux. This prowess, acquired by many multi-cultural individuals, is widely under-acknowledged, she suggests.

O’Grady’s authoritative voice reflects, with self-confidence and style, the integration of her subjectivity and her intellect. Her focus is “on the black female, not as an object of history, but as a questioning subject.” She continues: “In attempting to establish black female agency, I try to focus on that complex point where the person intersects with the historic and cultural.” The unequivocal centrality of the whole black female in O’Grady’s work marks her as a pioneer. This is ironic, since women of color, when placed in a global context, cannot correctly be classified as a “minority,” either in terms of race or gender.

The distinctive elegance that characterizes O’Grady’s work is also integral to her outspoken critique. Though media stereotypes might suggest otherwise, such elegance is frequently evident in many different black communities from Soweto and Kingston to Harlem, from Addis Ababa and Paris to Hartford.

This MATRIX exhibition features two separate installations by O’Grady: her debut into the New York art world as the fictional Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (1980-82) and her most recent work, Miscegenated Family Album (1994). Reconciling these related bodies of work, O’Grady has titled this two-part, diptych-like presentation The Space Between. In doing so, she inverts the apparently binaristic approach suggested by a diptych-based, two-part installation and urges the spectator to hybridize the content and meaning of the work in their own minds as part of the process of reception and reflection. Furthermore, O’Grady’s notion of hybridity is not only about seeking to blend but also about foregrounding the “already-blendedness” of all subjects.

The artist’s guerrilla performances as Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (1980-82) are now legendary. In the guise of this invented persona, clothed in a glamorous costume with a rhinestone and seed-pearl tiara and beauty-pageant sash in celebration of the Silver Jubilee of her coronation as “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (Inernationale) 1955,” O’Grady invaded several select New York art openings. She intentionally disrupted these occasions with short, inflammatory performance pieces in which she challenged the complacency of the audience with terse, polemical poems expressing her concerns on art and race.

O’Grady spent three weeks stitching together Mlle Bourgeoise Noire’s splendid gown and cape out of 180 pairs of previously-worn white gloves. It was important to the artist that these used gloves carried the unknown histories of the women who had worn them. White gloves, of course, were not only a sign of propriety and (speaking of hybridization) “good breeding,” but they also signal a condition of impaired efficiency and stifled action. The thirteen photographs exhibited here were taken in September 1981, when Mlle Bourgeoise Noire crashed a preview at The New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York City. The opening exhibition, Persona, presented nine artists whose work featured public presentations of invented surrogate characters. Mlle Bourgeoise Noire’s intervention protested the fact that all nine of the museum’s chosen artists were white.

Forthright expressions of anger by a woman, especially a black woman, are exceptional in our society. However, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire also references the revered tradition of black women “acting out,” that is, suddenly bursting forth, hands on hips, hurling expletives and disbelief at an outrageous situation. For O’Grady, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire’s rambunctious incursions made perfect sense. “Anger is my most productive emotion,” says the artist who is puzzled that the “enabling quality of anger” is so overlooked in our society. ( … )

The Harford Advocate (MBN), 1995

Patricia Rosoff, “Shadow Boxing with the Status Quo: Artist Lorraine O’Grady refuses to treat the art world with kid gloves,” The Hartford Advocate, pp. 21, 23, June 29, 1995.

“Lorraine O’Grady, The Space Between, MATRIX/127,” The Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT, May 21 – Aug 20, 1995. Review discusses this two-part installation exhibit: Miscegenated Family Album and Mlle Bourgeoise Noire.

June 29, The Hartford Advocate

****

( . . . ) Lorraine O’Grady, transfigured into a tiaraed beauty queen and identified by her sash as Mlle. Bourgeoise Noire 1955 [Miss Black Middle Class], barged her way onto the New York art scene in the early 1980s. Quite ceremoniously, though completely unannounced, she literally stormed in as a cultural critic, crashing hoity-toity art openings and demanding straight out that black artists “take off the white gloves” and “invade” the art world.

In this single considered act, O’Grady, English professor, Rolling Stone rock critic, former State Department economist and self-taught Egyptologist, brought together a variety of disparate threads in her life—her patchworked personal background, her intellectual strivings, her eclectic interests, her I-refuse-to-be-conventionalized outlook—and found herself mid-career standing in a place that denied none of thee roots and expressed them all. Under the commodious umbrella of performance art, O’Grady became, in short, an artist.

Now, as the scope of her work widens, leaving behind the more ephemeral theatricality of performance art and reaching for a more contemplative visual arena, O’Grady is featured in her first one-person museum exposure, Lorraine O’Grady: The Space Between, at the Wadsworth Atheneum. It’s a choice that acknowledges O’Grady’s emerging status “as an important national figure in contemporary art,” according to Andrea Miller-Keller, Emily Hall Tremaine curator of contemporary art at the Wadsworth Atheneum.

( . . . )

“The Space Between” is the title on the wall that greets the viewer. At every turn it is spaces we meet; juxtapositions, rather than entities, are the salient experience. In one room a grown made out of white gloves (one worn by Mlle. Bourgeoise Noire) is laid out under Plexiglass like an Egyptian mummy. Above this case, a shrill poem on the wall reads:

WAIT

wait in your alternate/alternate spaces

spitted on fish hooks of hope

be polite

wait to be discovered

be proud

be independent

tongues cauterized at openings no one attends

stay in your place

after all, art is only for art’s sake

THAT’S ENOUGH!

don’t you know

sleeping beauty needs more than a kiss to awake

now is the time for an INVASION!

A series of 13 documentary photographs wrapping two walls record O’Grady’s actual intrusion as Mlle. Bourgeoise Noire into an exhibition of nine white performance artists at the New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York In September 1981. Shown here as an intermingling of words, images, and physical memorabilia, there is little of the immediacy and shock that O’Grady must have generated when she swept into the gallery. There she distributed flowers, threw aside her cloak and lashed herself with a cat-o-nine-tails, then after pronouncing her poetic challenge, swept just as suddenly out of the room. Yet, as O’Grady explains it, what the shift from the event of performance to the quiet permanence of installation may have lost in confrontational dynamism, it has gained from the chance to “sit still” and let the ideas come together for the viewer. ( … )

Judith Wilson (MBN), 1991

Judith Wilson, Lorraine O’Grady—Critical Interventions, INTAR Gallery, New York, 1991.

Catalogue essay written for O’Grady’s first gallery solo exhibition, “Lorraine O’Grady,” INTAR Gallery, 420 W 42nd Street, New York City, January 21 – February 22, 1991.

****

( . . . ) Cultural Criticism: Mlle Bourgeoise Noire

“’Performance,’ as I conceive it . . . has nothing to do with a simple multiplication of media. In its most profound sense, ‘performance’ is a matter of artists shifting dimensions, putting themselves at risk by changing their accustomed relation to space/time.”

The February 17, 1980 opening at P.S. 1 of the exhibition “Afro-American Abstraction” was a watershed for O’Grady. “When I got there I was blown away,” she has said. “The galleries and corridors were filled with black people . . . who were interested in advanced art.” Ultimately, though, she was disappointed: “I felt that the art on exhibit, as opposed to the people, had been too cautious . . . that it had been art ‘with white gloves on’.”

It did not escape O’Grady, however, that several of the most venturesome artists in the show — Houston Conwill, David Hammons, Maren Hassenger, Senga Nengudi, and Howardena Pindell — were represented by a single dealer, Linda Goode-Bryant. The first and only Black gallery owner on 57th Street, Bryant had brought a bold, multi-cultural vision to the toney midtown Manhattan art scene during the mid- to late 70s. By 1980, the swelling real estate monster forced the young dealer to head for the New York artworld’s southernmost frontier, Tribeca. It was there that O’Grady began rubbing shoulders with members of the Black visual art vanguard in her capacity of volunteer at the relocated Just Above Midtown (JAM) — now officially “Just Above Midtown/Downtown” — Gallery.

JAM christened its new space with an exhibition called “Outlaw Aesthetics” that featured installations and performances by various artists. An opening night benefit offered paying guests edible art, a basement disco, and other “experiential happenings”. To an unusual degree, the event itself, rather than the art it celebrated, is what sticks in the mind ten years later.

There was an intoxicating sense that we, the buzzing throng of Black, White, and Brown bodies packing the room as tight as a rush-hour subway, were participants in something new, something meaningful in ways none of us could name yet — a sense that, in retrospect, was not uncommon at those art-related gatherings of the early 1980s at which the crowds were mostly young and the sites were previously unglamorous ones like the East Village or the territory south of Canal Street. As for the art at JAM that night, only one artist’s work permanently stamped itself on my brain.

At 9 p.m., when a light beige woman with cinnamon-colored hair entered the room wearing a rhinestone and seedpearl tiara, a floor-length gown and cape made of 180 pairs of white gloves, and a broad, beauty-pageant sash that proclaimed the bearer “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire 1955”, Lorraine O’Grady made her debut as a performance artist. Moving slowly through the crowd with her tuxedoed male escort, she flashed a glittering smile and asked assorted on-lookers “Won’t you help me lighten my heavy bouquet?” while proffering one of the 27 white chrysanthemums she clutched. As the flowers dwindled, it became evident that a white cat-o-nine-tails formed the core of the bouquet.

When the last bloom was distributed, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire handed her cape to her escort, who then offered a pair of over-the-elbow white gloves, which she carefully donned. Thus attired, she now began pacing the floor like a caged animal and lashing herself with the whip. Suddenly, at the height of her frenzy, she abruptly came to a halt, dropped the lash, and shrilled:

THAT’S ENOUGH!

No more boot-licking . . . No more ass-kissing . . . No more pos . . . turing . . .

of super ass . . . imilates . . .

BLACK ART MUST TAKE MORE RISKS!!!

Then this mysterious apparition swept through the hushed crowd and out into the night. ( . . . )