Miscegenated Family Album

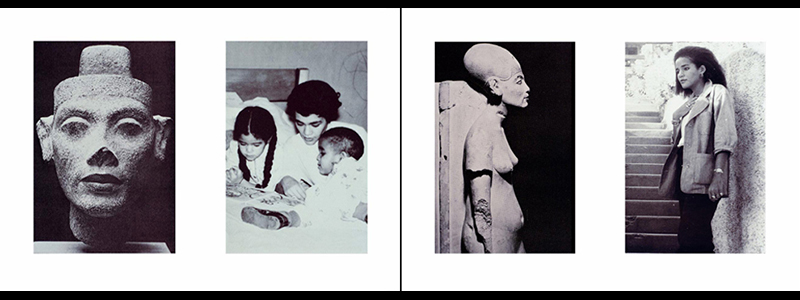

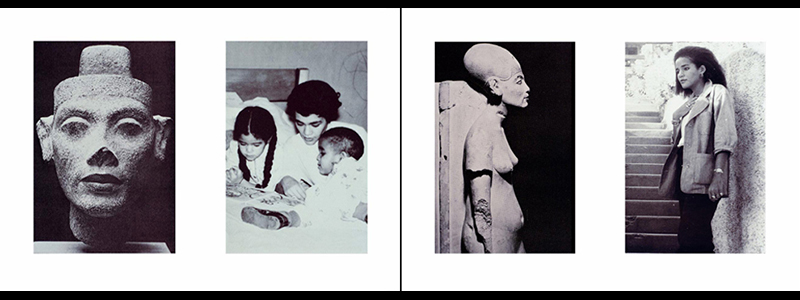

Miscegenated Family Album, O’Grady’s 1994 photo-installation of cibachrome diptychs, is perhaps her most complete and satisfying work. It had a long gestation period. Its 16 diptychs were selected from the 65 image pairs of Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline, the 1980 performance of mourning and reconciliation in which slides comparing her sister Devonia, Nefertiti, and their families were projected behind the artist’s live action. She retired the performance in 1988 following its presentation in Art As A Verb, curated by Leslie King-Hammond and Lowery Sims, because it now felt emotionally and theoretically redundant. However, Art As A Verb simultaneously featured her first wall installation, “Sisters,” a group of four doubled images taken from the performance. O’Grady soon decided that the quadriptych, shown in isolation from its larger context, was both too baldly political (one artist said it was more political than David Hammons’s “How Ya Like Me Now?” also in the show) and too pretty. She would turn down an invitation to exhibit it in the landmark Decade Show of 1990.

In 1994, she was able to present the full installation as she imagined it. While in residency at the Sharpe Foundation, she was invited to be in The Body as Measure at Wellesley’s Davis Museum. On the floor of her studio, color xeroxes of the 65 diptychs from N/DE were spread out, moved, deselected and rearranged. With the final grouping of 16 diptychs, it seemed to go past the personal and political limits of earlier versions to become “a novel in space,” one that could speak beyond words.

In the 1990s, Miscegenated Family Album was also shown at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford and at the Louisiana Museum in Denmark (where, wonderfully, its tiny dark room felt like the inside of a sarcophagus). In 2008, an edition was purchased by the Art Institute of Chicago and exhibited in its Permanent Collection Galleries. It also in 2008 received its first show in New York, at Alexander Gray Associates, O’Grady’s new gallery.

Brooklyn Rail (MFA), 2016

“Lorraine O’Grady, in Conversation with Jarrett Earnest.” Brooklyn Rail, pp. 56-63, print, February 3, 2016.

by Lorraine O’Grady in conversation with Jarrett Earnest, 2016

In this cover feature, her most important published interview to date, O’Grady discusses Flannery O’Connor as a philosopher of the margins, the archival website, working out emotions via Egyptian sculpture, Michael Jackson’s genius, and feminism as a plural noun.

****

( . . . ) Rail: I found the pieces from Miscegenated Family Album at the Carpenter Center very moving. There is a reference that it was made as a memorial for your sister who you had a complicated relationship with—could you give me more of the context? Egyptian funerary sculpture is not exactly sentimental—it’s not warm and fuzzy—but I think through cropping and pairing you coax out something extremely touching.

O’Grady: Not too long after my sister Devonia died, I found myself in Egypt. I was there three or four weeks. It was 1963 and I’d been working for the United States government so I’d made a stop at the Embassy almost as soon as I got off the plane, after several months in Ethiopia. I parked my suitcases there and went to cash my travelers checks at the American Express in the

basement of the Nile Hilton. As I was walking from the Embassy to the Hilton across the square, I looked around and I could not believe it—there were so many people who looked like me. I had never been anywhere like that before—it had not happened in Boston certainly, and it had not happened in Harlem. Downstairs in the American Express, behind the counter there were three agents, two Egyptian men and a young Egyptian woman, and I got into one of the three lines. The lines were filled with Danes and Germans. And there was me. When I got to the counter the young man who’d been speaking perfect English to the person ahead of me immediately started speaking Arabic. I said, “I’m sorry but I don’t speak Arabic.” He looked surprised and then from the other end of the counter I heard this voice, the young Egyptian woman, say “Oh, she’s such a snob!—she doesn’t speak Arabic!” At that point I knew the resemblance was not in my head, and I began to think more deeply about my general attraction to Egyptian aesthetics and what I’d always felt was a strong resemblance between my sister and Nefertiti.

Rail: It is an extremely simple idea: pairing images of Ancient Egyptian sculptures of Nefertiti with photographs of your sister— but the total effect is very complex, emotionally. It’s also interesting that that specific moment of Egyptian art, from the reign of Akhenaten, is the only instance you can really say: that looks like a specific, idiosyncratic individual.

O’Grady: I essentially became an amateur Egyptologist of the Amarna Period. Akhenaten, with his monotheistic religion, was a total aberration and a threat to the established powers, including the Theban priesthood. After he died, they destroyed all traces of that place. They erased Akhenaten and Nefertiti’s names from cartouches throughout the Two Lands.

( . . . )

Contributor Text, Paris Triennale (MFA), 2012

“Lorraine O’Grady: Contributor.” La Triennale: Intense Proximity.

© Lorraine O’Grady, 2012

Written to replace a curatorial text on the Triennale’s English website, the text describes the effect of O’Grady’s hybrid background on content and form in her work, elaborating this with respect to Miscegenated Family Album, her “novel in space” in the Triennale.

****

Conceptual artist Lorraine O’Grady uses performance, photo installation and video as well as written texts to explore hybridity, diaspora and black female subjectivity. Born in Boston to Jamaican immigrant parents, O’Grady was strongly marked by a mixed New England–Caribbean upbringing which left her an insider and outsider to both cultures. She has said, “Wherever I stand, I must build a bridge to some other place.”

O’Grady came to art late following several successful careers — as an intelligence analyst for the Departments of Labor and State, a commercial translator with her own company, and even as a rock critic for Rolling Stone and The Village Voice. Her first public art work, the well-known performance Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (1980-83), which critiqued the segregated art world of the time, was done initially at the age of 45. This broad background accounts, in part, for her distanced, critical view of the art world and for her eclectic attitude as an art maker. Ideas come first, then the medium to best execute them. However, the work’s apparently different surfaces are characterized by their unique amalgam of rigorous political content and formal elegance and beauty. Beneath the surface, there is often a unifying concern with hybrid identity.

The pejorative word “miscegenation,” coined in 1863 and then used for the post-Civil War laws making interracial marriage illegal — laws not struck down by the Supreme Court until 1967 — has been recuperated in O’Grady’s photo-installation title Miscegenated Family Album (1994). In this strongly feminist “novel in space,” O’Grady attempts to resolve a troubled relationship with her only sister Devonia, who died early and unexpectedly, by inserting their story into that of Nefertiti and her younger sister Mutnedjmet. Building on remarkable physical resemblances, the paired images span the coeval distance between sibling rivalry and hero worship through “chapters” on such topics as motherhood, ceremonial occasions, husbands and aging. At the same time, in O’Grady’s view of Ancient Egypt as a “bridge” country, the cultural and racial amalgamation of Africa and the Middle East which flourished only after its northern and southern halves were united in 3000 BC, both families, one ancient and royal, the other modern and descended from slaves, are seen to be products of nearly identical historic forces.

Email Q & A w Courtney Baker (MFA), 1998

Lorraine O’Grady Interview by Courtney Baker, Ph.D. candidate, Literature Program, Duke University.

Unpublished email exchange, 1998

The most comprehensive and focused interview of O’Grady to date, this Q & A by a Duke University doctoral candidate benefited from the slowness of the email format, the African American feminist scholar’s deep familiarity with O’Grady’s work, and their personal friendship.

****

( . . . ) Q: Re: Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline—In pairing images of Devonia with images of Queen Nefertiti were you trying to say something about class? You mentioned in an interview that you were criticized (or feared being criticized) for equating your (sister’s) family with royalty.

A: Well, of course, I was. In the beginning, I was always trying to say something about class. In those days, pre-Jeffersons, pre-Cosby, it’s hard to imagine how invisible the existence of class was. But luckily I was also talking about other things, or the images wouldn’t continue to live. The deepest motivation for N/DE was my desire to say something about sibling rivalry and its obverse, hero worship, and the ways in which both are affected by death. Then there was my usual need to critique Western art history (here, sub-division: Egyptology). It was another of my overdetermined art pieces. But without those uncanny resemblances, I don’t think I could/would have said anything.

At one level, I’d been as frustrated by the teacher pointing to the map of Africa and saying, “Children, this is Africa, all except this, and this is the Middle East,” as the next black kid. So to that extent, the piece was Afrocentric.

But even the most cursory glance at Egyptian culture (the structure of kingship, religion, etc.) is enough to convince one of, at the least, an African substratum. The denial of this is on the level of white historians’ refusal to entertain evidence for Thomas Jefferson fathering Sally Hemings’ kids—you are not dealing with rationality here. Nevertheless, it was annoying to have my work lumped with simplistic Afrocentric arguments: i.e., lineage as some sort of ridiculous salvation rather than as a sign of complexity.

I have often thought that if I’d come across a family photo album in a flea market with equally remarkable resemblances to my own family, it would have sparked my imagination just as well.

But that itself raises a set of interesting questions: How might such a found album have come into being? Where might it have come from? What would the family’s racial composition and class have been? If, as I believe, we do inhabit a world where hybridity is a norm, then the family setting off those resemblances could as easily have been a white as a black one. But the class question is a bit more tricky. While it needn’t have been royal or even aristocratic, I think it would have required a sophisticated family to produce responses so intense. Comparisons with a working-class or peasant family too easily might have become academic in the worst way.

( . . . )

Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline, 1997

“Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline,” in College Art Association, Art Journal, Winter 1997, Vol 56, No 4: Performance Art: (Some) Theory and (Selected) Practice at the end of this Century, pp 64-65. Guest editor, Martha Wilson.

© Lorraine O’Grady

In this article for Art Journal, Winter 1997, the special issue on performance edited by Martha Wilson, O’Grady focuses first on Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline, then discusses its relationship to Miscegenated Family Album, alluding to the advantages and disadvantages of the move from performance to photo installation.

****

Abstract: A performance artist relates her creation of a piece called Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline. The work juxtaposes the image of the artist’s deceased older sister and an ancient Egyptian queen. It parallels the artist’s troubled relationship with her sister and Nefertiti’s troubled relationship with the queen’s younger sister. The work attempts to make a statement regarding the nature of sibling relations and the limits of art as a vehicle for reconciliation.

In 1980, when I first began performing, I was a purist – or perhaps I was simply naive. My performance ideal at that time was “hit-and-run,” the guerilla-like disruption of an event-in-progress, an electric jolt that would bring a strong response, positive or negative. But whether I was doing Mlle Bourgeoise Noire at a downtown opening or Art Is . . . before a million people in Harlem’s Afro-American Day parade, as the initiator, I was free: I did not have an “audience” to please.

The first time I was asked to perform for an audience who would actually pay (at Just Above Midtown Gallery, New York, in the Dialogues series, 1980) – I was non-plused. I was not an entertainer! The performance ethos of the time was equally naive: entertaining the audience was not a primary concern. After all, wasn’t it about contributing to the dialogue of art and not about building a career? I prepared Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline in expectation of a one-night stand before about fifty cognoscenti and friends. It was a chance to experiment and explore. Performance’s advantage over fiction was its ability to combine linear storytelling with nonlinear visuals. You could make narratives in space as well as in time, and that was a boon for the story I had to tell.

My older sister, Devonia, had died just weeks after we’d got back together, following years of anger and not speaking. Two years after her unanticipated death, I was in Egypt. It was an old habit of mine, hopping boats and planes. But this escape had turned out unexpectedly. In Cairo in my twenties, I found myself surrounded for the first time by people who looked like me. This is something most people may take for granted, but it hadn’t happened to me earlier, in either Boston or Harlem. Here on the streets of Cairo, the loss of my only sibling was being confounded with the image of a larger family gained. When I returned to the States, I began painstakingly researching Ancient Egypt, especially the Amarna period of Nefertiti and Akhenaton. I had always thought Devonia looked like Nefertiti, but as I read and looked, I found narrative and visual resemblances throughout both families.

Though the invitation to perform before a seated audience at Just Above Midtown was initially disconcerting, I soon converted it into a chance to objectify my relationship to Dee by comparing it to one I could imagine as equally troubled: that of Nefertiti and her younger sister, Mutnedjmet. No doubt this was a personal endeavor, I was seeking a catharsis. The piece interwove partly subjective spoken narrative with double slide-projections of the two families. To the degree that the audience entered my consideration, I hoped to say something about the persistent nature of sibling relations and the limits of art as a means of reconciliation. There would be subsidiary points as well: on hybridism, elegance in black art and Egyptology’s continued racism.

Some people found the performance beautiful. But to tell the truth, few were sure of what I was up to. Nineteen eighty was seven years before the publication of Martin Bernal’s Black Athena, and a decade before “museumology” and “appropriation” reached their apex. As one critic later said to me, in 1980 I was the only one who could vouch for my images. I will always be grateful to performance for providing me the freedom and safety to work through my ideas; I had the advantage of being able to look forward, instead of glancing over my shoulder at the audience, the critics, or even art history.

Performance would soon become institutionalized, with pressure on artists to have a repertoire of pieces that could be repeated and advertised. I would perform Nefertiti several more times before retiring it in 1989. And in 1994, now subject to the exigencies of a market that required objects, I took about one-fifth of the original 65 diptychs and created a wall installation of framed Cibachromes. Oddly, rather than traducing the original performance idea, Miscegenated Family Album seemed to carry it to a new and inevitable form, one that I call “spatial narrative.” With the passage of time, the piece has found a broad and comprehending audience.

The translation to the wall did involve a sacrifice. Now Miscegenated Family Album, an installation in which each diptych must contribute to the whole, faces a new set of problems, those of the gallery exhibit career. The installation is a total experience. But whenever diptychs are shown or reproduced separately, as they often must be, it is difficult to maintain and convey the narrative, or performance, idea. As someone whom performance permitted to become a writer in space, that feels like a loss to me.

Thoughts on Diaspora and Hybridity (MFA), 1994

“Thoughts on Diaspora and Hybridity.” Unpublished lecture at Wellesley College delivered to the Wellesley Round Table faculty symposium on Miscegenated Family Album.

© Lorraine O’Grady, 1994

Written shortly after the “Postscript” to “Olympia’s Maid,” this lecture delivered to the Wellesley Round Table, a faculty symposium on Miscegenated Family Album, takes a retrospective look at O’Grady’s earlier life and work through the prism of cultural theory.

****

( … ) Miscegenated Family Album, the installation which is premiering now, is in fact extracted from an earlier performance, Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline, which I did in 1980. Both pieces have benefited from the fact that, since 1980, the work of post-colonialist thinkers such as Said, Homi Bhabha, Paul Gilroy, Gayatri Spivak, and Trinh Minh-ha has shown that our old idea of ethnicities and national cultures as self-contained units has become outmoded in an era when “There is a Third World in every First World, and vice versa.” In fact, we were never, even in situations of the most extreme brutality, hermetically sealed off from each other. This realization, marked out in cultural studies, has been paralleled in contemporary art with an additional understanding: that the intellectual, emotional and political factors from which art is made have themselves not been segregated. We do not look at or produce art with aesthetics and philosophy over here, and politics and economics over there.

In fact, as these false barriers fall, we find ourselves in a space where more and more the entrenched academic disciplines appear inadequate to deal with the experience of racially and imperially marginalized peoples. Perhaps the only vantage point from which the center and the peripheries might be seen in something approaching their totality may be that of exile, or diaspora. As the 21st century approaches, we could be facing a prolonged period of intellectual revisionism. Perhaps all of us, the newly de-centered as well as the already marginal, will have to adopt (in the spirit of DuBois’s old theory of “double consciousness”) what Gilroy has called “the bifocal, bilingual, stereophonic habits of hybridity.”

It’s true, diaspora inevitably involves sexual and genetic commingling. But this aspect of hybridity, though fascinating in itself, is not essential to the argument I am making. “Diaspora,” a Greek word for the dispersion or scattering of peoples, includes by extension the lessons that displaced peoples learn as they adapt to their hosts or captors. It is diaspora peoples’ straddling of origin and destination, their internal negotiation between apparently irreconcilable fields that can offer paradigms for survival and growth in the next century. Well, I should say that the caveat is if, and always if, they choose to remember the process of straddling and negotiation and to analyze the resulting differences. A simplistic merging with the host or captor always beckons. But I do think that in a future of cultural crowding, the lessons of diaspora and hybridity can help us move beyond outdated originary tropes, teach us to extend our sensitivities from the inside to the outside, perhaps even help us maintain a sense of psychological and civic equilibrium.

As an artist I like to be concrete. Perhaps this example from my own practice will show what I mean by hybridity, how a process and an object can be more than one thing at a time.

Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline was the 1980 performance from which I later developed Miscegenated Family Album. It was an early attempt to treat these ideas in terms of my personal background. Of course, the performance wasn’t created in an emotional and intellectual vacuum: it was a working through of a troubled, complex relationship with my dead sister, Devonia, a relationship that ran the gamut from sibling rivalry to hero worship and was itself a sort of hybrid.

The performance functioned on a lot of levels. On one level, that of a certain emotional distance, it dealt with the continuity of species experience—the old plus ça change, c’est plus la même chose, or the more things the more they stay the same. While this idea might appear essentialist on the surface, I don’t feel there is any necessary conflict between permanence and change. To me, the continuity reflected in the piece’s dual images was a kind of geological substratum underlying what was in fact a drastic structural diversity caused by two very different histories. The similarities in the two women’s physical and social attitudes didn’t negate the fact that Nefertiti had been born a queen and Devonia’s past included slavery. The performance was not “universalist” in the current sense of the term.

( . . . . ) I do think every good artwork is over-determined, with multiple composing elements. One of the primary conscious elements in Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline was something I would call, that [is] an oxymoron. For subjectivity is the baby that got thrown out with the bathwater in the binarism of postmodern theory. When Western modernist philosophy’s “universal subject” finally became relativized (we know which race, we know which gender), rather than face life as merely one of multiple local subjects, it took refuge in denying subjectivity altogether. In addition, contemporary theory stoutly denies its enduring binarism. But through its almost Manichean inability to contain nature and culture in a common solution, it tends to rigidly oppose nature and the “personal” on the one side, and culture and the “historic” on the other. All my work, including Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline and Miscegenated Family Album, is devoted to breaking down this artificial division between emotion and intellect, enshrined in the Enlightenment and continued by its postmodern avatars. It makes the historic personal and the personal historic.

In my performances and photo installations, I focus on the black female, not as an object of history, but as a questioning subject. In attempting to establish black female agency, I try to focus on that complex point where the personal intersects with the historic and cultural. Because I am working at a nexus of things, my pieces necessarily contain hybrid effects. In Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline, the aesthetic choice to combine personal and appropriated imagery worked, I think, in both traditional and postmodern ways. Using images with so uncanny a resemblance to my late sister and her family helped objectify my relationship to her and to them and may have given viewers a traditional narrative catharsis. On the other hand, because personal images were compared to images that were historic and politically contested, a space was created in which to make visible a previously invisible class. They were also able to open out to other cultural, i.e. impersonal questions. The piece was not “individualist.”

Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline and the later Miscegenated Family Album attempted to overcome artificial psychological and cultural separations through the strategies of hybridism. The work I am doing now in my studio continues these preoccupations but locates them in the more recent 19th century.

( … )

Brooklyn Museum, 2010

Patrick Amsellem, “Brooklyn Museum Object of the Month: Miscegenated Family Album.” Brooklyn Museum website, August 6, 2010.

Patrick Amsellem, Associate Curator of Photography, Brooklyn Museum, blogs a tribute to Miscegenated Family Album. Analyzing the work’s intellectual and emotional success at the museum, Amsellem writes that MFA “immediately became a favorite.”

****

It’s when a work of art is able to communicate on many different levels at the same time – when it can speak to audiences on both an emotional and intellectual level – that I often feel it’s the most successful. That’s why I was thrilled when we were able to acquire Lorraine O’Grady’s Miscegenated Family Album last year.

Something remarkable happens when O’Grady combines her own family portraits with ancient Egyptian imagery. Some of these juxtapositions are tender and intimate, with mood and gestures strikingly fusing family and family matters millennia apart. The work immediately became a favorite of our installation Extended Family and it merges the personal with the historic, relating beyond the Contemporary Galleries to the Museum’s world renowned collection of Egyptian Art.

Miscegenated Family Album consists of sixteen pairs of black-and-white and color portraits. Each framed pair juxtaposes images of members of the artist’s family, often her sister Devonia, with images mostly portraying the Egyptian queen Nefertiti and her family. The work grew out of O’Grady’s 1980 performance, Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline, which took place in front of a larger series of projected images of a similar kind. Devonia died unexpectedly at the age of thirty-seven before the sisters had time to reconcile their troubled relationship. The performance was a way for the artist to mourn her dead sister, her only sibling, and work through their fraught and complex bond.

The use of Egyptian imagery came naturally to O’Grady who found a physical resemblance between her sister and the Egyptian family imagery she chose. In the same way, she found similarities in the family histories. Nefertiti’s sister Mutnedjmet plays an important role in many of the pictures and the Egyptian queen disappeared from public life at an age close to Devonia’s at the time of her death. Egyptian art from this period around 1340 BC is known for its realistic and informal depictions of family life and its intimate portrayal of affection between family members. (The Brooklyn Museum has a wonderful collection of portrait reliefs from this period, including the piece called A Mother’s Kiss, which O’Grady used for her work—see below.

At the same time as the subject matter is deeply personal, through it O’Grady also addresses issues of class, racism, ethnography and African American art. The piece is also a commentary on hybridity. Born in Boston in 1934 to West Indian parents, O’Grady always approaches biculturalism in her art and acknowledges the importance of the diaspora experience for her life and work: the need to reconcile conflicting values and different backgrounds, and, as O’Grady writes, the necessity “to build a bridge to some other place.”

Miscegenated Family Album will remain on view until September 5.

Ancient Art Podcast (MFA), 2009

Lucas Livingston, “Episode 22: Nefertiti, Devonia, Michael.” Ancient Art Podcast, on Monday, 8:04pm, July 6, 2009.

Complete transcript of podcast by Lucas Livingston, an Egyptologist associated with the Art Institute of Chicago, which discusses Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline and Miscegenated Family Album in detail. Also a YouTube video with high-quality images.

****

Transcript

( . . . ) While the notion of a black African cultural and ethnic influence on Ancient Egypt is frequently discussed today, we should bear in mind that in 1980, when O’Grady first performed Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline, this was still seven years before the publication of Martin Bernal’s highly acclaimed and criticized work Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization.

Now, I’m not saying that the sub-Saharan African influence on Egyptian civilization is definitively confirmed. It’s still a hotly debated issue with many shades of gray. Ancient Egypt was a huge nation surviving thousands of years. And during that time there was frequent contact with surrounding countries, including periods of foreign occupation. By the time of Nefertiti and Akhenaten in the mid to late 14th century BC, parts of Egypt were pretty ethnically diverse, which likely got even more ethnically diverse as the centuries led up to the Ptolemaic period of Cleopatra. I’m excited to see that the University of Manchester museum will be hosting a conference on “Egypt in its African Context” on October 3rd and 4th, 2009. You can read about the conference online ( . . . )

One point that we need to bear in mind when considering the ethnicity of Ancient Egyptians is the baggage we bring with us to the discussion. We all have a lot of baggage, but what I’m specifically talking about is the whole preoccupation with ethnicity. I don’t know about kids these days, but not too long ago when I was a wee lad, every American schoolboy or girl could tell you their heritage, breaking it down by the percentage. Blame it on the African diaspora, Western imperialism, or Ellis Island, but I would argue that this obsession with the argument over whether the Ancient Egyptians were black, white, Greek, Berber, or other is something of a modern development. The Egyptians were an ethnically diverse lot and they would have said to us “So what!?” What mattered to the Egyptians was that you were Egyptian. You don’t hear of Ancient Egyptian race riots.

The beauty of O’Grady’s Miscegenated Family Album is that it looks more than skin-deep. O’Grady draws a few parallels between her sister Devonia and Nefertiti. They both marry, have daughters, and perform ceremonials functions — one as a priestess, the other as a bride. Devonia passed away at the age of 37 before the two sisters could fully reconcile their differences. Nefertiti suddenly vanished from the written record after the 12th year of Akhenaten’s reign, around the year 1341. Back in the 1980’s when O’Grady was researching for her performance piece Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline, the prevalent theories for Nefertiti’s disappearance involved her death or fall from grace, perhaps due to Akhenaten elevating another consort to Great Royal Wife. Akhenaten did, in fact, elevate someone else to be the Great Royal Wife at that time — his eldest daughter Meretaten.

Nefertiti may have died, or some argue that she was elevated to co-regent, like a king-in-training. Another theory is that Akhenaten’s fourth daughter, Neferneferuaten Jr., became co-regent. She’s junior, because another one of Nefertiti’s names was also Neferneferuaten, and since the co-regent was named Neferneferuaten ( … ) well, hence the confusion as to exactly who was co-regent. After the death of Akhenaten around 1336 BC, we then have king Smenkhkara, ruling just a short while before our boy King Tut came onto the scene.

Another parallel that O’Grady draws is between herself and Neferitit’s apparent younger sister Mutnedjmet. Just as the younger O’Grady was left behind after her sister’s sudden and tragic passing, Mutnedjmet would also have been abandoned after Nefertiti’s sudden disappearance, according to the theories at the time. Just to bring everything else up to current theory, contrary to popular speculation, there’s no evidence that Nefertiti’s sister is the same Mutnedjmet, who was queen to the later king Horemheb. Also the more widely accepted translation today of Nefertiti’s sister’s name is Mutbenret, which is spelled exactly the same in hieroglyphs. But those are both minor technicalities that have little to no impact on O’Grady’s overall work. The importance of Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline and Miscegenated Family Album is that the immediate physical resemblance in the framing of O’Grady’s family members with figures of ancient history is indicative of deeper sentiment and associations. The past becomes an idealized and humanized film through which our own lives are filtered and compared ( . . . )

Nick Mauss in Artforum (MFA), 2009

Nick Mauss, “The Poem Will Resemble You: The Art of Lorraine O’Grady.” Artforum Magazine, vol. XLVII, no. 9, pp. 184-189, May 2009.

Mauss’s article for Artforum is, with Wilson’s INTAR catalogue essay, one of the most extended and authoritative pieces on O’Grady’s oeuvre to date. It was one-half of a two-article feature that also included O’Grady’s artist portfolio for The Black and White Show.

****

( . . . ) For O’Grady, Rivers, First Draft explores a new psychological terrain in which political agency bravely includes the right to expose vulnerability in public: “I confess, in my work I keep trying to yoke together my underlying concerns as a member of the human species with my concerns as a woman and black in America. It’s hard, and sometimes the work splits in two—within a single piece, or between pieces. But I keep trying, because I don’t see how history can be divorced from ontogeny and still produce meaningful political solutions.”

This splitting finds its most poignant realization in the sixteen-part photo installation Miscegenated Family Album, 1980/1994, a piece that actually traces its origins to an earlier performance. One month after Mlle Bourgeoise Noire’s invasion of Just Above Midtown, O’Grady was invited by the gallery’s founder-director, Linda Goode Bryant, to participate in a performance showcase called “Dialogues.” O’Grady’s contribution, Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline, 1980, juxtaposed the story of her relationship to her estranged sister, Devonia, with a chronicle of Nefertiti’s relationship to her younger sister, Mutnedjmet ( . . . ) Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline enacted legitimate pain in a complicated work of mourning, triangulating between the present and two irretrievable pasts. In the installation of photographic diptychs that developed fourteen years after the performance, O’Grady gave form to the concept of a miscegenated family album by framing a selection of the double images she had first projected as slides. The counterintuitive pairing of interdynastic “siblings” creates a third temporal image, a bridge that is neither visual nor textual, a space of not knowing. While Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline articulated the struggle to mend loss and division, the juxtaposed images that constitute Miscegenated Family Album brilliantly illuminate one another, creating what O’Grady calls “a novel in space.” Nefertiti, by her proximity to Devonia, is lifted into the present, and her own idealized bearing restores something like dignity to Devonia. “With the diptych, there’s no being saved, no before and after, no either/or,” O’Grady writes. “It’s both/and, at the same time. With no resolution, you just have to stand there and deal” ( . . . )

Johanna Burton, 2008

Johanna Burton, “Lorraine O’Grady, Alexander Gray Associates.” Artforum, pp 301-2, Dec 2008.

Artforum’s first review of a solo exhibit by O’Grady. Discusses the first New York showing of the full Miscegenated Family Album installation, at Alexander Gray Associates, NYC, September 10 – October 11, 2008.

****

In 1980, at Just Above Midtown Gallery in New York, Lorraine O’Grady presented her first official (which is to say first invited) public performance piece, Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline. The work followed closely on the heels of the artist’s more (in her words) “hit-and-run” foray into performance, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire — in which she showed up at New York art openings as the title character, unannounced and uninvited, calling attention to those deeply raced, gendered, and classed environments — and likewise concerned itself with issues of representation.

But Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline made unapologetic strides into more overtly autobiographical terrain. Indeed, it was, in part, a working through of a painful event: Two decades prior, when the artist was in her late twenties, her older sister, Devonia, with whom she’d had a strained relationship, had suddenly and unexpectedly died. Although the two women, after years of estrangement, had briefly reunited, the deep ambivalence that had defined their relationship lingered. During a trip to Cairo shortly after Devonia’s death, O’Grady — who was born to mixed-race Jamaican immigrant parents — recalled, in an article the artist wrote in 1997 for Art Journal, that “the loss of my only sibling was being confounded with the image of a larger family gained.”

That O’Grady had identified so strongly with Egypt (where, she claimed, she had found herself “surrounded for the first time by people who looked like me”) — and, more precisely, with ancient Egypt — was of course complicated in its own right. For while she found there “the image of a larger family” at a moment when her own was experiencing loss, she was necessarily constructing a kind of fantastical, irrational, intentionally off-kilter legacy for herself. Going through her own old family albums and art history books devoted to Nefertiti and her clan, she picked images of women from both, creating side-by-side comparisons that literally placed the two genealogical lines on par.

Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline, then, comprised O’Grady performing live in front of slide projections of these paired images. Not many people saw that performance — the usual small crowd of fifty people or so probably have memories of its enactment in time and space. But the photographic pairs did not disappear. In 1994, the artist constructed a sixteen-part series of Cibachrome diptychs from those images she had used previously as projections, and the resulting images have been shown in various configurations over the past decade and a half. At Alexander Gray Associates, the series, titled “Miscegenated Family Album,” its elements now nearly three decades old, was shown in its entirety for the first time in New York.

Here a striking image of Devonia (“Dee”) glancing over her left shoulder is placed alongside an eerily similar bust of Nefertiti; there an image depicting a sculpture of Nefertiti’s daughter, Merytaten, alongside a photograph of Devonia’s daughter, Candace; and elsewhere, Dee as matron of honor at a wedding alongside a relief sculpture of Nefertiti performing a lustration. In every case, there is no question that undeniable, even uncanny, likenesses float between the pairs O’Grady has assembled. But this is more than morphology and not, actually, any insistence by the artist that her family carries royal blood. Instead, it posits an uneasy symmetry — one based in both desire and despair — between singular histories and the stories told about entire cultures, while also nodding to the complicated relationships found in every family.

Not an artifact of the performance but still related to it, “Miscegenated Family Album” operates to recall the urgent questions regarding ideologies of identity at the time O’Grady was first working, but also makes clear that such urgency has hardly subsided today. Indeed, though the through-line to O’Grady’s “album” is the conflicted relationship between two sisters (if Devonia is likened to Nefertiti, Lorraine herself is aligned with Nefertiti’s sister, Mutnedjmet), the overall logic suggests that we continually ask ourselves just where we stand in relationship to every picture.

Modern Painters, 2008

Claire Barliant, “Lorraine O’Grady, Miscegenated Family Album, Alexander Gray Associates.” Modern Painters, Nov 2008.

Discussion of framing as a technique of meaning in O’Grady’s conceptual photo-installation.

****

Alexander Gray Associates (New York) September 10–October 11, 2008

Photo: Lorraine O’Grady, “Sisters III” (1980/1994). Cibachrome prints, 26 x 37 in. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York

Passe-partout, a french term meaning both a “master key” and a technique for matting a photograph or painting, was adopted by Derrida to explain the way an image is metaphorically framed by its context. And attention to framing, both literal and metaphorical, is key to understanding Conceptual artist Lorraine O’Grady’s 1980/1994 photographic installation Miscegenated Family Album. On first glance, the work’s pairing of family photos with ancient statues of Nefertiti seems an elaborate and fantastic way to establish royal lineage, but this family album has little to do with genealogy. Instead it is a subtle recounting of O’Grady’s strained relationship with her older sister, Devonia, a rift that was not resolved before Devonia’s untimely death at 37. O’Grady finds a striking parallel between her sister and Nefertiti, who disappeared in her late thirties, leaving behind six children and her younger sister Mutnedjmet. All the images in the album are scaled identically, eliminating hierarchy and reinforcing a poetic link between the two families. bouquet in hand, Devonia as a matron of honor is juxtaposed with a relief of Nefertiti performing a purification ritual, while the wistful, faraway look worn by Kimberly (Devonia’s daughter) is mirrored by a bust of Nefertiti’s daughter Maketaten. O’Grady is best known for her performances as Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, who crashed art openings in the ’80s in an attempt to draw attention to artworld apartheid, but here she sets aside the struggle to assert her identity. Far from being polemical, this somber series delves into the experiences that shape our sense of self, exploiting the frame as a passe-partout that conflates the historical and the personal, uniting human beings across time and space.

Art Institute of Chicago, 2008

MISCEGENATED FAMILY ALBUM, Art Institute of Chicago, 2008.

In 2008, the AIC became the first museum to purchase the full Miscegenated Family Album installation. The initial exhibit was that summer, in a Permanent Collection gallery shared with the work of Felix Gonzalez-Torres.

****

LORRAINE O’GRADY

Miscegenated Family Album, 1994

As an artist of African, Caribbean, and Irish descent, Lorraine O’Grady has mainly focused on representations of black female subjectivity, often through the lens of family, literary and art-historical narratives. All of her work combats the elimination of difference across a spectrum of social concerns while championing the positive values of hybridization. In her own words she has been “obsessed with the reconciliation of opposites: past and present, conscious and unconscious, black and white, you and me.” O’Grady’s culturally complex childhood often left her feeling that she “belonged everywhere at once and nowhere at once,” but through it she learned to skillfully negotiate a range of social, racial, and class milieus.

Miscegenated Family Album, the artist’s masterpiece, is a series of 16 diptychs, each containing an image of the ancient Egyptian queen Nefertiti paired with an image of the artist’s deceased sister, Devonia Evangeline O’Grady Allen, or members of their respective families. The physical resemblances between individuals within any given diptych are sometimes startling. Both families, in fact, reflect the consequences of generations of cross-cultural exchange and interracial marriage. (Miscegenation, the procreation between members of different races, was still illegal in 15 states in 1967, when such laws were finally overturned by the United States Supreme Court.) The dramatic contrast between the evolution of Nefertiti’s family, which resulted from advantageous political alliances, and that of Devonia’s forebearers – subjected into slavery and then dominated – sexually and otherwise – resonates throughout the series. In defiant triumph, O’Grady illuminated the regal bearing of both families.

Andrea Miller-Keller (MFA), 1995

Andrea Miller-Keller, “Lorraine O’Grady: The Space Between,” in Lorraine O’Grady / MATRIX 127,” Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford CT, pp. 2-7, 1995.

Brochure article written for the one-person exhibit “Lorraine O’Grady / MATRIX 127,” The Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT, May 21 – Aug 20, 1995.

****

( . . . ) For O’Grady, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire’s rambunctious incursions made perfect sense. “Anger is my most productive emotion,” says the artist who is puzzled that the “enabling quality of anger” is so overlooked in our society.

O’Grady’s contrastingly quiet installation Miscegenated Family Album is a series of sixteen Cibachrome diptychs, each containing an image of the ancient Egyptian Queen Nefertiti paired with a corresponding image of the artist’s deceased sister, Devonia Evangeline O’Grady Allen, and/or members of their two families. The physical resemblances between the two are sometimes startling. Both families, in fact, reflect the consequences of generations of cross-cultural exchange and inter-racial marriage.

Miscegenation, the procreation between members of different races, was still an illegal practice in fifteen states in 1967, when such laws were finally overturned by the United States Supreme Court. Says O’Grady, “The word ‘miscegenated’ refers both to the album’s aesthetic and to the process of racial hybridization by which each family was founded.”

The dramatic contrast between the evolution of Nefertiti’s family, largely the result of advantageous political alliances, and that of Devonia’s forebears, subjugated into slavery and then dominated sexually and otherwise, resonates throughout this installation. In defiant triumph, the artist illuminates the regal bearing of both families.

Contemporary scientific research along with the radical shift in demographics over the past several decades combine to challenge the accuracy of our notions of self-contained ethnic, racial, or national groups. These categories, which have long dominated our patterns of social and economic organization, are increasingly understood to be artificial constructs largely contingent on the values and interests of those who hold power.

Miscegenated Family Album has its origins in an earlier performance piece, Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline (1980), that represented O’Grady’s attempts to come to terms with the complexity of her feelings about her sister Devonia, who was eleven years her senior and died unexpectedly at the age of 38. As the emblem of success for the O’Grady family’s social aspirations, Devonia had been placed on a pedestal. With her sister’s untimely death, O’Grady had to face the ambivalence of her feelings about Devonia’s acceptance of the family’s bourgeois values. At the same time, the artist struggled to reconcile both her idolization of her sister and a long-standing sibling rivalry with her feelings of loss.

Underlying O’Grady’s appropriation of images of this ancient dynasty is an understanding of the shifting placement of Egyptian civilization within the Western canon. O’Grady, an ardent student of history and an amateur Egyptologist, recalls that even as a young grammar school student, the removal of Egypt from the study of Africa left her feeling that something important had been subtracted from her legitimate heritage. Eventually questioning the prevailing, racist interpretations of traditional colonialist Egyptologists, O’Grady learned that the much-admired early Egyptian Dynasties (I–IV) — those whose contributions to world culture (and to Hellenic civilization in particular) are considered most significant — were, in fact, black Africans of southern Egypt. Over centuries of imperial politics, these rulers inter-married, and royal blood lines, as we can see in Miscegenated Family Album, became racially mixed.

In the past decade, O’GRADY has moved away from performance, choosing instead formats in which the convergence of such complex ideas “can be held still and studied.” Miscegenated Family Album is not a series of photographs offering a linear narrative. Rather, it is an installation piece in which time is collapsed and, using the diptych format, O’Grady’s personal, historical, and cultural concerns do indeed, intersect.

( . . . )

The Hartford Advocated (MFA), 1995

Patricia Rosoff, “Shadow Boxing with the Status Quo,” The Hartford Advocate, pp. 21, 23, June 29, 1995.

“Lorraine O’Grady, The Space Between, MATRIX/127,” The Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT, May 21 – Aug 20, 1995. Review discusses this two-part installation exhibit: Miscegenated Family Album and Mlle Bourgeoise Noire.

****

Artist Lorraine O’Grady refuses to treat the art world with kid gloves

( . . . ) Now, as the scope of her work widens, leaving behind the more ephemeral theatricality of performance art and reaching for a more contemplative visual arena, O’Grady is featured in her first one-person museum exposure, Lorraine O’Grady: The Space Between, at the Wadsworth Atheneum. It’s a choice that acknowledges O’Grady’s emerging status “as an important national figure in contemporary art,” according to Andrea Miller-Keller, Emily Hall Tremaine curator of contemporary art at the Wadsworth Atheneum.

O’Grady is a black woman whose work subjectively addresses her own experiences, yet she refuses to be characterized in any way as a spokesperson for the black experience. It’s a big point with her, an issue of self-determination and of fundamental respect for the complexity of blackness. Her work in general targets just this kind of oversimplification, which she feels comes from the hierarchical Western notion that things must be either all white or all black, all good or all evil, all male or all female, all culture or all nature. Instead O’Grady’s fascination is with “hybrid” culture. In her images she seeks to establish the very connections between what society chooses to call opposites. She tries to demonstrate that culture is not a matter of racial stratification but of complex and ongoing negotiation, sometimes white or black but more often both white and black at the same time.

This concentration on ties rather than rifts is the core of her radicalism and gives her work its distinctly shaded character. Its determined focus on the richness of a blended culture revisits the old WASP idea of the melting pot from an entirely new angle. “I was drawn to O’Grady’s work,” says Miller-Keller, “because it challenged a variety of accepted cultural paradigms: the binarism that holds our Western thinking in a vice, the concept of race which is not in fact a scientifically verifiable concept, and the notions of elegance and where it can be located. Above all,” Miller-Keller adds, “the work is so beautiful and so damned smart.”

The exhibit at MATRIX illustrates Miller-Keller’s points and demonstrates what O’Grady means when she calls visual art “a heightened form of writing.” The gallery is divided in two. Each half presents a different body of work, both of which began as performances and have been developed into documentary form of a less-transitory character. The relation between them is neither direct nor directed in the exhibition, which is unusually explication-free for MATRIX, a space that prides itself on making ideas accessible to the uninitiated public. The point of this curatorial restraint is revealed in the character of the show, wich is animated by what the artist calls its “spatial” rather than “linear” relatedness, that is, by the fact that it makes sense somewhat mysteriously overall but not in neat little logical steps. This is precisely the point.

( . . . )

Likewise, in “Miscegenated Family Album,” the installation in the other half of the MATRIX space, an evolution from slide presentation to black-and-white photographs allows a more patient savoring of imagistic irony. The presentation pairs ceremonial images of Egyptian Queen Nefertiti with family photographs of O’Grady’s sister, Devonia Evangeline. The linking is incongruous, accomplished by singular parallels of feature, pose or gesture but involving as well all manner of connections between O’Grady’s intimate knowledge of both subjects.

Some of these links can be deduced from the diptych titles: “Worldly Princesses—Left: Nefertiti’s daughter Merytaten, Right: Devonia’s daughter Kimberly,” for example. Many, however, can only be sensed. It is the enlarging aspect of these musings that give this room its lingering powers. The very-familiar image of female family members gussied up at a reception, distributing smiles, beverages and pieces of cake, s placed next to ritualized relief carving of Nefertiti making an offering to the sun disk Aten, arms raised, beverages in hand, each ray of light also possessing hands reach back reciprocally. The bizarre mix of elements—hand, plates, arms, offering, formality of dress—bridge the two images with a sense of “rightness” that overcomes laborious limitations of fact and make tedious any questions of “why.” The truth of these positionings is a subjective matter, involving neither art history nor sermons on social posturing, and likewise the strength of the work, while unverifiable in any specific proof, is in the fact that it is simply fascinating. Significantly for the artist, however, the very fact that it is a hybrid invention is its essential positive.

( . . . )

Carol Dougherty, 1994

Carol Dougherty, “The Object of History and the History of Objects.” Unpublished museum handout, Wellesley College, Wellesley MA, 1994.

Handout by a professor of Greek and Latin for the premiere of O’Grady’s installation Miscegenated Family Album in Body As Measure, The Davis Museum and Cultural Center, Wellesley, MA, 1994.

****

“(My history) is to be a possession for all time rather than an attempt to please popular taste.” Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War 1.22

“The British say they have saved the Marbles. Well, thank you very much. Now give them back.” Melina Mercouri, Greek Minister of Culture, asking the British government to return the Elgin Marbles to Athens, The London Times, May 22, 1983

When Thucydides wrote his famous history of the Peloponnesian Wars, he not only produced a masterful account of the monumental conflict between Athens and Sparta at the end of the fifth century B.C.E., he also shaped the way we have come to define history—as factual, impartial, and objective. Furthermore, disdaining immediate public approval, Thucydides wanted to create “a possession for all time,” and it is precisely this choice of metaphor that has produced our now pervasive view of “history” as an object of value, something that can be owned and appropriated like the famous Elgin marbles that once stood upon the Parthenon. Today’s academic journals and editorial pages, for example, are full of battles over “the stolen legacy” of the ancient Mediterranean—were the Egyptians black? Have northern Europeans suppressed valuable and influential contributions to intellectual and cultural life made by ancient Egyptians? Did the Greeks borrow from the Egyptians or vice versa? These debates stem in large part from Thucydides’s success in packaging the past as a metaphorical commodity. He has given us the very language to describe history as “mine” or “yours,” as an artifact in danger of being stolen, in need of being defended, demanding to be regained.

Lorraine O’Grady also uses valuable—and thus contested—artifacts to explore the relationship between ancient Egypt and contemporary America in her work Miscegenated Family Album. In a series of sixteen diptychs, she matches photographs of twentieth-century African-American women (members of her own family) with published photographs of ancient Egyptian sculpture. Although not an historian, O’Grady reminds us of a very different way of casting the relationship between objects and history. Rather than enshrining history as an artifact that controls interpretation and asserts ownership over what happened, the ancient sculpture opens up a dialogue—a discussion of how history continues to influence our present experience as well as how contemporary issues and ideological battles determine exactly what we value from the past. The title Sisters (assigned to images 1-4), for example, emphasizes a relationship of equality, reciprocity, and shared experience rather than insisting that chronology determine the nature and direction of cultural influence. The bust of Nephertiti certainly adds stature and historical context to the 1940s picture of O’Grady’s own sister. Yet the contemporary photograph, remarkable in its similarity in light, pose, and gesture to that of the ancient sculpture, recharges and animates the weighty monument typically forced to represent the significance and substance of African culture. The collective impact of the series encourages us to construct a multiplicity of connections between the many sets of images.

A generation before Thucydides, Herodotus first coined the term “history” to describe his account of the events leading up to and including the Persian Wars. History, as Herodotus invented it, is not a matter of objectivity (although he includes objects in his account—they produce stories). His was a process of enquiry: a histor is an arbitrator, someone who adjudicates competing claims. More important, Herodotus’s approach is noisy. His text preserves a multiplicity of voices, the cacophony of conflict, and does not always offer an opinion about who is right. Ever aware of the instability of world affairs, Herodotus’s historiographical method lays contradictory claims side by side, forever open to discussion and debate. In his account of Egypt and its relation to Greek religion and culture, for example, he refuses to choose a Greek or an Egyptian Heracles. Instead, Herodotus makes room for both: “I heard the following story about Heracles—that he was one of the Twelve Gods; but as for the other Heracles, the one the Greeks know about, I was not able to hear a word anywhere in Egypt.” (The Histories, 2.43.1)

With a similarly open-ended strategy, O’Grady refuses to freeze the relationship between contemporary African-American women and ancient Egypt within the frame of her work. In this series of paired photographs, the artist juxtaposes past and present, stone and flesh, Africa and America, history and politics, art and life. She then leaves us to assume the authoritative role of histor: to compare, to evaluate, to make connections, to determine the nature of the family ties. Lorraine O’Grady shows that in spite of Thucydides’s masterful attempt, history cannot be reduced to the status of a polished marble statue—a possession for all time. These artifacts will always be part of the picture, but their real value lies not as objects of custody battles for the past. Instead, she suggests that we begin to dispossess history of its images of ownership and commodity and begin to value in their place the many stories these artifacts continue to generate—an ongoing and reciprocal dialogue between the past and the present.

Carol Dougherty Assoc. Professor, Dept. of Greek and Latin Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA.

Boston Globe, 1994

Christine Temin, “Wellesley’s ‘Body’ also has a brain,” The Boston Globe, pp. 49, 58, Friday, September 23, 1994.

Review of The Body As Measure, The Davis Museum and Cultural Center, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA, Sep 23 – Dec 18, 1994. Refers to O’Grady’s first exhibition of Miscegenated Family Album as “the most extraordinary work in the show.”

****

WELLESLEY — “Not another show about the body!” will doubtless be some people’s reaction to “The Body as Measure,” which opens today at Wellesley College’s Davis Museum. Theme shows about the human body have sprouted up nearly everywhere in recent seasons; in the Boston area, the Museum of Fine Arts’ “Figuring the Body” and MIT’s “Corporal Politics” come to mind. So Wellesley’s show, when it was announced, seemed superfluous.

It’s not. that’s partly because curator Judith Hoos Fox has taken an original tack. Unlike other “body” shows, hers doesn’t deal with functions and fluids; there’s no blood or urine. It’s not a messy exhibition. Nor is it aggressive or angry: The politics here are subtler. Finally, the show succeeds because of the talent of its curator. “The Body as Measure” is, in fact, a perfect example of curatorial intelligence. Fox has pulled together nine artists from the United States, Canada an Germany: They weren’t an obvious, easy-to-identify group. She’s selected pieces that date from 1963 to 1993, editing superbly to create a gallery where works connect visually and philosophically.

You hear one work before you see it — before you even enter the gallery, in fact. The sound of the artist’s shoes walking endlessly back and forth are part of Denise Marika’s travels between two bathroom medicine chests, her blurry form appearing inside them, on a wax shape that looks like a sink. Her body is measuring both time and space; she’s a human clock.

The first work you actually see is Canadian artist Micah Lexier’s “Book Sculptures: Three Generations (Female).” which is also about measuring [see photo]. Lexier makes stacks of fake “books” out of wood (which is of course the raw material of books), and on the stacked spines he prints photographs of three generations of women standing back-to-back as if to see who is taller. The lines between the books divide the stack into even units of measurement; the curving spines make the books look as if they’ve been printed on Venetian blinds.

The theme of family relationships is also addressed by Elizabeth Cohen and Lorraine O’Grady. Cohen’s “Flashpoint” is a humming horizontal installation whose main elements are a row of hundreds of toe tags — the kind used in a morgue — and a row of repeating, alternating photographs of a beauty salon chair and a doctor’s examining table. On some of the tags is text (the written word is another important theme in the show) about an adolescent brother and sister. He is sick; she is well. He is linked to the doctor’s office; she to the beauty shop. But as the text progresses, the siblings exchange identities. She starts to

Unlike other ‘body’ shows, hers doesn’t deal with functions and fluids; there’s no blood or urine. It’s not a messy exhibition. Nor is it aggressive or angry: The politics here are subtler.

sound like a hypochondriac; he begins to like having his hair done. Cohen has thought through details that reinforce the eeriness of “Flashpoint,” from the fact that the examining table and the chair are unoccupied to the color of the frames — the awful aqua common to both beauty shops and hospitals.

O’Grady’s “Miscegenated Family Album” is the most extraordinary work in the show, a series of photographs of Egyptian sculpture juxtaposed with old photos of O’Grady’s own family [see photo]. Her sister, Devonia, a beautiful African-American woman who died young, is twinned with Nefertiti. Devonia’s daughter Candace is paired with Nefertiti’s daughter Ankhesenpaaten, Devonia’s husband with Nefertiti’s, and so on. The parallels extend to poses and facial expressions: When Devonia is in a celebratory mood, so is Nefertiti. That all of these correspondences are coincidental is astonishing. Spanning many centuries, “Family Album” makes Nefertiti’s family seem oddly contemporary, and O’Grady’s seem something like a period piece. It’s a startling and haunting work.

( . . . )

The strengths of this show don’t end with the contents of the gallery. The ancillary programming is a model that every other museum in the area should look at closely. Wellesley professors from several departments have written essays about aspects of the show, available as handouts. They bring perspectives other than straight art history: Carol Dougherty, for example, from the department of Greek and Latin, starts her essay on O’Grady with Thucydides. Through November, there will be lectures and films related to “The Body as Measure” (call 283-2051 for information). And the show comes with a fine catalog whose pages are held together with ordinary staples, a touch of whimsy intended to reflect the element of metallic precision and repetition in the show.

Judith Wilson (MFA), 1991

Judith Wilson, Lorraine O’Grady—Critical Interventions, INTAR Gallery, New York, 1991.

Catalogue essay written for O’Grady’s first gallery solo exhibition, “Lorraine O’Grady,” INTAR Gallery, 420 W 42nd Street, New York City, January 21 – February 22, 1991.

****

. . . . Further Adventures: From the Nile Valley to 125th Street. . . and Back Again. . .

Four months [after first announcing herself as Mlle Bourgeoise Noire], when O’Grady performed next at JAM, she unveiled a work completely unlike the one in which she had made her debut. Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline was a departure in almost every conceivable way. Where the tone of Mlle Bourgeoise Noire had been caustically satirical, the new piece was elegiac. Where the first work had lampooned Black aesthetics in the 1980s by linking them with social conventions of the 1950s, the new work lamented the tragic fates of an ancient Egyptian queen and a modern African-American “princess.” Where the earlier piece had smudged the line between life and art by utilizing “real” space/time and inviting a degree of audience participation, the new performance operated in the symbolic arena and mythic time of ritual, and re-established conventional boundaries between the artist/performer and her spectators.

Its Caribbean beauty contest (a reference to O’Grady’s West Indian ancestry) and its send-up of Black bourgeois proprieties —, the current piece contained autobiographical elements. Devonia Evangeline was the artist’s elder sister, a woman whose fairy tale life came to a shockingly sudden end at age 38. The performance consisted of images of the artist’s late sibling and other family members, which were projected alongside images of the Egyptian queen who had died at age 37 and members of her family, while O’Grady’s taped voice delivered an elliptical account of both women’s lives. Finally, stationed in front of the giant heads of Nefertiti and Devonia Evangeline that were being beamed on the wall, O’Grady enacted a ritual prescribed by the Egyptian Book of the Dead. “Hail, Osiris! I have opened your mouth for you, I have opened your two eyes for you\,” the artist chanted. With these words, she donned a mantle even denser with symbolism than Mlle Bourgeoise Noire’s white-glove-laden cape.

On the one hand, while the ritual she invoked was meant to insure the deceased’s immortality, her rendition underscored the futility of such gestures. On the other, by drawing the viewer’s attention to the uncanny parallels between the facial features and poses of O’Grady’s relatives and ancient Egyptian royalty, the artist simultaneously drove several controversial points home. Ancient Egypt’s African heritage, Black America’s multi-racial ancestry, and the existence of a pre-Cosby era African-American aristocracy were all visibly evidenced by the juxtaposed photographic imagery. Thus, while she failed to restore her lost sister to sight and breath, O’Grady succeeded in giving voice to the stifled history of a great civilization, and opening our eyes to a seldom seen aspect of a people, as well as a virtually unknown social class.

A further component of Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline and an especially crucial one was its frank exposure of the highly volatile and visceral attachments between femaie relatives — sisters, mothers and daughters. In some ways, the work can be seen as the artist’s attempt to resolve conflicts left suspended in the wake of her sister’s sudden death. But insofar as Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline blends female autobiography with ceremony and history, it can be seen as a step in the direction of her next major theme — what she has called “Black female self-reclamation.”

(. . . .)

(. . . .) 1983 closed on a grim note for the artist, who learned in December that her mother was afflicted with Alzheimer’s Disease. Her artistic career came to a halt while she devoted the next four and a half years to her mother’s care.

Finally forced to place her declining parent in a nursing home, O’Grady resumed activity in 1988 when she received an invitation to participate in the exhibition Art As A Verb. For that show, she had eight slides from Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline made into four Cibachrome diptychs. The new work, called simply Sisters I, II, III, IV, juxtaposed images of her sister (Devonia Evangeline) and the Ancient Egyptian queen, Nefertiti, with images of herself and Nefertiti’s younger sister, Mutnedjmet, followed by images of Devonia Evangeline’s two daughters with images of Nefertiti’s daughters. Stripped of the tragic details of the earlier work, the new piece zeroed in on Black female family ties, an ancestral legacy that includes the civilizations of the Nile Valley, and the “mulatto” cultures of both ancient Egypt and contemporary America. The following spring, O’Grady gave one last performance of the original Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline at the Maryland Art Institute in Baltimore.

( . . . .)