The First and the Last of the Modernists

In The First and the Last of the Modernists, an installation for the 2010 Whitney Biennial, two of O’Grady’s careers—rock music critic and avant-garde artist—met unexpectedly.

She’d taught the work of Charles Baudelaire for two decades at SVA. The 19th-century French poet and art critic known as the father of modernism had appealed to her for his harshly intimate poetry and for the fierce bravery of his leap from romanticism to modernism. To an unusual degree, he’d embraced the new conditions posed to European art by industrial revolution and the subsequent process of empire which had led to a disorienting encounter with “others.” In 1842, the year he turned 21, the emerging poet faced a new world, one where the artist could no longer safely make art in God’s image but would now have to make it in his own and society’s. Without the support of old certainties, the transition from being a servant of God to being a kind of god in one’s self was dangerous, and it was impossible not to admire the way Charles, though not always successful, met it headlong.

Baudelaire’s capacity for the unique distance from his own culture needed to fully accept and reflect it had been increased, O’Grady felt, by the life he shared with Jeanne Duval, the young black woman he met that year, who was his same age and with whom—without benefit of clergy and, more surprisingly, without pressure of offspring—he would live for more than 20 years. Seeing Europe through Jeanne’s eyes and experiencing her life as part of his own must have expanded him, she thought. Where Baudelaire scholars and critics often derided Duval in frankly racist terms, she saw Jeanne as the quintessentially postmodern woman, grappling inter-racially with life in diaspora and a proto-global economy The sheer length of their relationship spoke for itself. And Jeanne, the 19th-century emigrant from Haiti to Paris, also provided her a window through which to view her own mother Lena, who’d emigrated from Jamaica to Boston just 80 years later at the close of World War I. She gradually interchanged Lena’s image and voice with Jeanne’s in the work she was doing to understand Jeanne and Charles’s relationship.

A decade later, when Michael Jackson died, like many O’Grady had cried as though a member of her own family had gone but couldn’t say why. A former Prince fan, she’d stopped following Michael after the Thriller album. Now she plunged into the world of fan sites and YouTube videos to locate the source of her tears and was shocked that his genius had continued to develop while she had moved on. The extent of his brilliance and his humanity overwhelmed her. Comparisons to Charles inevitably suggested themselves. . . the divine self-belief, the ambiguous sexuality, the fanatic devotion to craft, the drugs, the unironic aspiration to greatness, the flamboyant clothing and makeup.

She was struck most by the price they had each paid for taking the role of the artist so seriously. What could be more godlike or quixotic than Michael’s belief that he could unite the entire world through his music—or more amazing than how close he came?

They seemed to embody industrialization in its purest forms. Charles forever walking Parisian streets that were being torn up and re-routed to accommodate the massive influx from the countryside. . . Michael with lungs permanently damaged from a childhood spent in Gary when the steel mills still belched fire. And they’d experienced, in opposite directions, the fantastical fluid movement of money and class, from above to below and vice versa, that the modern world made possible.

At the extremes of talent and devotion represented by Baudelaire and Jackson, distinctions of European and non-European, of high and low culture seemed superseded by the view of artists responding to shared conditions. In her work on Charles and Jeanne, she’d come to see Europe’s two modernist turning points—Baudelaire’s own 1857 Flowers of Evil, in which even lesser poems not about her felt shaped from Jeanne’s living body, and Picasso’s 1907 Demoiselles d’Avignon, in which carved African sculptures transmogrified into the bodies of European prostitutes—as evidence that, at an important level, modernism was an encounter between the self and the other. But since everyone is a self, and everyone is an other, modernism had to contain everyone’s responses to the encounter. It couldn’t be just a statement or a monaural discussion, it must be more a cacophony.

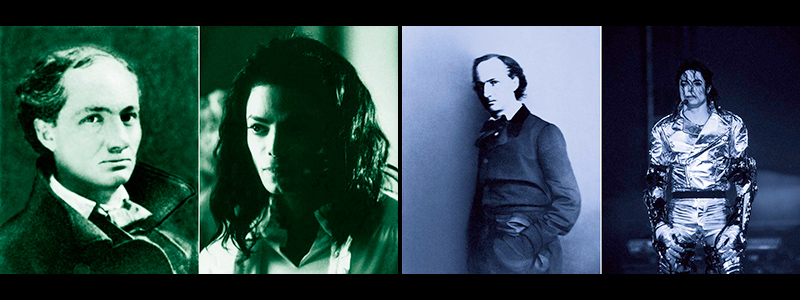

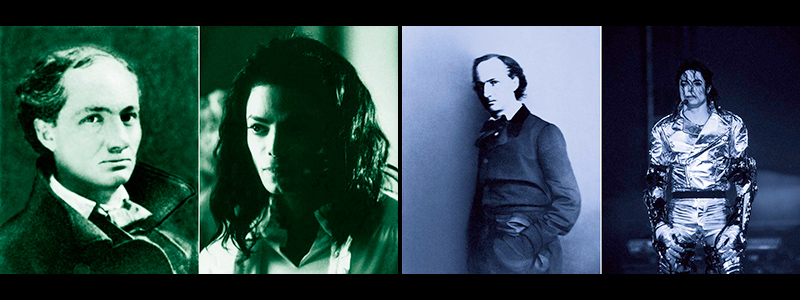

When O’Grady was selected for the Whitney Biennial three months after Michael’s death, she created The First and the Last of the Modernists as a modest installation substituting Michael’s image for those of Lena and Jeanne. There were few enough images of Charles, and only a handful were the right age and quality for a project with Michael. Finding possible matches from among the more than 30,000 Michael images circulating online was arduous, and there’d be endless cropping and adjusting and color. But seeing it on the wall, she was surprised. She felt it would keep teaching her. She’d already learned so much about the work on Charles and Jeanne/Lena that now she would have to go back and restart it afresh.

Brooklyn Rail (FLM), 2016

“Lorraine O’Grady, in Conversation with Jarrett Earnest.” Brooklyn Rail, pp. 56-63, print, February 3, 2016.

by Lorraine O’Grady in conversation with Jarrett Earnest, 2016

In this cover feature, her most important published interview to date, O’Grady discusses Flannery O’Connor as a philosopher of the margins, the archival website, working out emotions via Egyptian sculpture, Michael Jackson’s genius, and feminism as a plural noun.

****

( . . . ) Rail: Could you describe your piece The First and the Last of the Modernists (2010), a sequence pairing images of Charles Baudelaire with Michael Jackson?

O’Grady: You know I taught a course on Baudelaire and Rimbaud for twenty years at SVA. There are many things about Charles that Michael shared, an overpowering father being just one. But if I had to say which of the two was the better in his own art form, I would say Michael was. What shocks people when they see them side-by-side is they think: how can you compare a pop star with an avant-garde poet? When I look at them, I see Michael as the greater genius.

Rail: When I looked at those photos of Michael Jackson I can’t help but think of him as “suicided by society.”

O’Grady: The reason for doing the piece was to try and understand why I loved Michael so much. I knew why I loved Charles—that was clear to me. I loved him for his aesthetic courage, for his openness to a changed historic reality, his eccentricity, his relationship to Jeanne Duval. Michael was a very sad and lonely figure; he’d always been sad and always been lonely, but he did the best he could. He’s one of the few child prodigies who ever fulfilled his talent so completely as an adult. But on an interpersonal level, he was severely limited. I myself don’t believe he actually had sex with any of those boys—I was relieved of that attitude. But I think he was a fool in many ways. He thought children came to him with no agenda, but he didn’t seem to realize their parents had multiple agendas. I feel he played out his childhood with those kids in a way that only someone who can do whatever they want, might. He was self-indulgent, a limited person in the way child prodigies often are. You look through history and see that most are not exactly the greatest people.

Rail: Through making this piece, what did you ultimately understand about loving Michael Jackson?

O’Grady: I’ve learned a lot about Michael, as a flawed object still worthy of my love. But I’m not sure I understand what caused my tears when he died. I suspect there are a lot of people out there like me. I know when Michael died there were a billion people crying, and there were probably half a billion who didn’t know why they were crying. They think he’s beautiful, they think he’s talented, an incredible musician—but that doesn’t account for the love. How did he manage to reach so many different people? And they don’t know why. I think there’s something ultimately about Michael’s vulnerability—that vulnerability he always displayed, even as a small child, and the unhappiness he had even as a child, and at the same time the resignation with which he lived with that in order to achieve glamor—that made you identify something of yourself with him.

( . . . )

Four Diptychs (FLM), 2010

In Pétunia: magazine féministe d’art contemporain et de loisirs, issue 2, pp. 43-46, Summer 2010.

© Lorraine O’Grady, 2010

The French feminist magazine Petunia’s invitation to create a centerfold sparked O’Grady’s piece in the 2010 Whitney Biennial, The First and the Last of the Modernists. The text documents her decision to contrast images of Baudelaire and Michael Jackson. [Also posted as a related material under The Studies for Flowers of Evil and Good]

****

June 1, 2009

For months I’ve planned to resume work on Flowers of Evil and Good, the photo-installation on Baudelaire and his black common-law wife Jeanne Duval and ultimately my mother Lena, which I began in 1995. I adore Baudelaire and taught his poetry for years at the School of Visual Arts here in New York. But as much as I love his poetry, I love him as a man because of Jeanne. Two decades! Longer than most couples I know, and without benefit of either wedding or kids. As a black woman who’s had white partners, I don’t have to speculate to say Charles learned a few things about his own culture he wouldn’t otherwise have known. . . that kind of insider-outsider position makes a leap from romanticism to modernism look easy. Although Jeanne is present in every line of his poetry, even when he writes about Mme Sabatier, she is absent everywhere. Where is her own voice? It isn’t until I hear her in the voice of my mother Lena, born 80 years later into a world which has not yet changed, that I can begin to know who Jeanne is. It is summer now, and I am eager to get back to work. But my computer crashes, and those early files are now buried in half a terabyte of data I must transfer from DVDs to a new external drive.

June 25, 2009

Oh, it is boring! Transferring and organizing is taking weeks. To prevent my mind from numbing, I live on the internet simultaneously. When the news first comes through, for hours I don’t believe it. But it’s true, Michael is dead. And now I am bawling uncontrollably. How could that be? I have always been a Prince fan! Where do my tears come from? Soon I am plunged into Google, into fansites, into YouTube. I maniacally download videos while continuing my data transfer (because I suspect the videos will quickly disappear), pull thousands of images, and read seemingly every article written in the aftermath plus others going back dozens of years. I am dumbfounded. Those who thought he hadn’t produced anything since Thriller had simply stopped listening and looking. MJ and Prince were so unalike, why did we feel we had to choose?

August 11, 2009

Now the data transfer is finished, I’ve begun to put Flowers of Evil and Good in order. . . images of Mama, Aunt Gladys, Aunt Vy, and Jeanne on one side, images of Charles on the other. My friend Mary Beth has taken a place in Greenport, on the North Fork of Long Island, and invited me to stay. She rises early morning, I wake midday, we meet for walks along the harbor and dinner out. In between, there is time spent on organizing the old Flowers of Evil and Good files and on a new obsession I can only name “Michael.” But the more I learn, the more he becomes conflated with Charles, the more similar the two seem—the pivotal turn each gave to his art form, the perfectionism, the absurd need to be different, the ambiguous sexuality. No one will aspire to greatness that un-ironically again. And if Picasso and Mozart had fathers who surrendered, Charles and Michael seem to share a father (and step-father) who cannot be overcome. In Greenport, an invitation comes to contribute to the French feminist journal Petunia. I say yes and hint that the piece “will relate to French culture.” Michael has temporarily replaced Jeanne and my mother. There is a piece here. I don’t know what it is, but there is time for it to emerge. Two male lesbians. Brothers.

September 28, 2009

Working on the mountain of files for Flowers of Evil and Good, I try not to think about the unnamed piece. But today, with only 10 hours notice, I am visited by the curators of the Whitney Biennial. “What will you do for the exhibit?” they ask. I answer spontaneously, as if I already knew: “Four diptychs on Charles Baudelaire and Michael.” Later, the piece has to be named. I will call it The First and the Last of the Modernists. The name is a risk, of course. But peeling back the cultural assumptions of Europe will always be like scraping off a tattoo.

Interview by Cecilia Alemani (FLM), 2010

“Living Symbols of New Epochs.” Interview by Cecilia Alemani. Discussion of development and meaning of The First and the Last of the Modernists. Text in English and Italian. Images of FLM, Miscegenated Family Album, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, and Cutting Out the New York Times. In Mousse Magazine, issue 24, pp. 100-108, Summer 2010.

Mousse Magazine, Milan, 2010

The Mousse interview, done after the Whitney Biennial opening, elaborated on O’Grady’s piece for that exhibit, The First and the Last of the Modernists, and its relation to her decades of teaching Baudelaire and to her work-in-progress Flowers of Evil and Good. [Also posted as a related material under The Studies for Flowers of Evil and Good]

****

CA: I would like to speak in this interview about your contribution to the 2010 Whitney Biennial, the work The First and the Last of the Modernists (2010). The piece is composed by four photographic diptychs depicting a seemingly unusual couple: Charles Baudelaire and Michael Jackson. The French poet has previously appeared in your work, in particular in Flowers of Evil and Good, a photo installation portraying Baudelaire and his black muse, common-law wife Jeanne Duval ( . . . ) What does Jeanne and her relationship with Baudelaire represent for you?

LOG: At first I was fixated on their having stayed together for 20 years without either wedding or children, on the diminution of self in maintaining even a dysfunctional relationship so long after sexual obsession has disappeared. But soon I began to see these two aspects of Charles, the relationship with Jeanne and the meeting of modernism’s challenges, as somehow connected.

So many forces were colliding in Europe when Jeanne and Charles came of age — the chaos of industrialization, sudden shifts of rural populations to the cities, colonies established to shove raw materials into the always open maw of factories, Europe’s first real encounter with the “other.” Modernism was the aesthetic attempt to understand and control and reflect all of this. In the period of romanticism, it had been so easy to see God in the daffodils, in babbling brooks that ran through the trees. It was still easy even for the artist in cities to view himself as a servant, making art in God’s image. But now the city had changed. One had to see God and beauty in homelessness, in the oil slick on a mud puddle, in the noise and greed. And Charles was one of the first who could do this. I suppose you might say that the modernist moment was the first time art had to be made without God, without guideposts. We’d soon see even the alternative to God, rationalist intellect, being discarded as an incomplete tool ( . . . )

CA: Going back to The First and the Last of the Modernists, here Baudelaire appears paired with another icon, Michael Jackson, who died in June 2009. According to the title, the work seems to depict the two fathers of our modern culture, the first one a key figure for western modernism and the latter the king of American pop culture. Are you a fan of Michael?

LOG: When Michael died, I couldn’t stop balling like a child, as if a member of my own family were gone. But where had those tears come from? I had been a Prince fan! The piece about Charles and Michael was the culmination of the effort to learn why I’d sobbed so uncontrollably that day.

CA: How did you get involved with his music and his myth?

LOG: Before making my first public art work in 1980 at the age of 45 with the performance Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, I’d had several careers. My undergraduate degree from Wellesley College was in economics and Spanish literature. I’d been among other things an intelligence analyst for the Department of State, a literary and commercial translator, a civil rights activist, a housewife. But nothing ever satisfied me. In the early 1970s, I left Chicago where I’d lived with my second husband and came to New York to be with a lover who’d managed rock bands and was now head of publicity for Columbia Records.

I didn’t want to be just a pretty rock chick, some guy’s “old lady” going to parties and concerts. So I began writing about rock and pop music — the first above-ground review of Bruce Springsteen for The Village Voice, the first article on reggae published in Rolling Stone, a cover story on the Allman Brothers, reviews of the New York Dolls and Sly and the Family Stone. Pretty eclectic. The Jackson 5, fronted by little Michael, had been huge and were beginning to decline. I didn’t write about them. They were simply part of the air we breathed.

By 1982 when Michael was dominating the world as a solo act with Off the Wall and Thriller and Prince had broken through with Controversy, I’d found a life and career as a visual artist that would never bore me and was just another pop culture consumer. What made us have to choose between them? Between the lineages of James Brown and Parliament Funkadelic? Perhaps it was like Baudelaire vs Rimbaud. Some spaces can only be occupied in alternation.

CA: What did Michael represent for you?

LOG: After he died, in an obsessive search for the source of my own tears, I plunged into the internet for months and emerged stunned. We’d all known that Michael was a talent like no other. But the demonization of his character (and the rock establishment’s need to keep the world safe for Bruce and Elvis?) had created a consensus that after Thriller he had lost his way. We’d stopped listening and looking. It was the self-consciousness of his achievements that most surprised me, the control he exercised over everyone and everything around him. Quincy Jones responsible for Thriller? Think again. No album was ever more deliberately crafted or had a more ambitious agenda. Masterpieces tailored for every demographic, with the outcome firmly in mind—to break the ghettoization of black talent in Billboard’s “r&b” chart forever. He’d been horrified by the treatment of Off the Wall, for which he’d won just one Grammy, as a “soul” singer.

It’s hard not to lapse into hyperbole when thinking about Michael. Don Cornelius, the creator of Soul Train, said that when he first saw Michael in a variety show two years before the family signed with Motown, he felt like he was in one of those cartoons where the two-ton safe falls out of the sky and lands on your head. An 8-year-old who could already sing as well as Aretha, dance as well as James Brown, and control an audience with Jackie Wilson’s aplomb! And all the evidence on YouTube showed that, in the annals of child prodigies, he was one of the rare ones who could keep developing until the end. I found myself returning to Baudelaire to make sense of him.

CA: What do they have in common, Charles and Michael, in spite of their very different origin? What happens when two different worlds and times clash?

LOG: They were so much alike, Charles and Michael. The similarities I felt in their lives—their indeterminate sexuality, their urgent need to be different from the norm, the drugs, the flamboyant clothes, the makeup, and the father and step-father too young and sexually vital ever to be overcome. Somewhere beyond that lay their similarity as intellectual symbols.

I really saw them not as figures of two different modernisms but rather as two ends of a continuum. If modernism was the aesthetic attempt to deal with industrialism, urbanization, the de-naturalization of culture, and the shock of difference, then it was an effort in which all sides shared and were equally affected—from Charles trying to find his way in the stench of the torn-up streets of Baron Haussman’s Paris, to Michael with lungs permanently impaired from a childhood in Gary when the steel mills still belched fire.

While the old dichotomies between white and black cultures, and between entertainment and fine art, are understandable—it’s hard to live on both sides simultaneously—the hierarchies between these imagined oppositions seem not just passé but fundamentally untrue. When I drew a line from Charles’s Les Fleurs du Mal, written out of Jeanne’s living body, to Picasso’s Les Demoiselles, made with abstract African sculptures, and on to Michael’s insertion of his own body into black-and-white film clips through the miracles of cgi in This Is It, it seemed the triangulation of a circle in which all sides were contained.

What’s most striking about Charles and Michael as artists is the similarity of their attitudes. The modernist artist who could no longer be the servant of God would always be tempted by a perceived obligation to become God. And no one succumbed to the temptation more than these two. It was there in the relentless perfectionism that limited their output, in the fanatical domination of their craft and its history, in the worship of their instrument. I find it so touching to think of Michael warming up for one to two hours with his vocal coach before going on stage or into the studio. And what could be more quixotic, imitate God more than the desire to unify the whole world through music? The amazing thing is how close he came—the most famous person on the planet, a billion mourners crying at his eulogies. I never found the source of my own tears. The search had exhausted me. I’d kept ricocheting between loving him unreasonably and thinking about him analytically. In the end, King of Pop seems such an inadequate term for him. I couldn’t have done The First and the Last if that’s all he was. He and Charles had lived out the modernist myth of the suffering artist to the point of cliché, but there was more to both of them than that.

The first of the new is always the last of something else. Charles was both the first of the modernists and the last of the romantics. He was bound to forever live in the forest of symbols. And Michael may have been the last of the modernists (no one can ever aspire to greatness that unironically again), but he was also the first of the postmodernists. Will anyone ever be as ideal a symbol of globalization, or so completely the product of commercial forces? In the end, the two, together and in themselves, were perfect conundra of difference and similarity. When I replaced Jeanne and Lena with Michael and put them on the wall, I couldn’t decide whether they would be seen more as lovers or as brothers.

Hyperallergic, 2014

Jillian Steinhauer, “Baudelaire, Michael Jackson, and Modernism.” Hyperallergic, 2014.

One of my favorite pieces included in Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art at the Studio Museum in Harlem earlier this year was Adam Pendleton’s “Lorraine O’Grady: A Portrait” (2012). The video captures O’Grady, a pioneering black feminist artist, telling the story of her career in art. Pendleton shakes up the narrative a bit with abrupt cuts and unusual perspective, but the most fascinating part of the video is unquestionably O’Grady herself, speaking smartly, thoughtfully, and eloquently about racism and sexism in the art world as well as her own work. She seems to possess an incredible magnetism and magnanimity.

Unfortunately “Lorraine O’Grady: A Portrait” isn’t online anywhere, so I can’t include it here. But there is a video on YouTube, thanks to Performa, that conveys some of what captivated me about O’Grady that day at the Studio Museum. It’s a recording of her talking about her work “The First and the Last of the Modernists ” (2010), which pairs photographs of Charles Baudelaire and Michael Jackson. As she explains in the Performa video, O’Grady is “obsessed” with the two men, and she sees a unique connection and parallel between them: “Charles was the first modernist. There will never be another modernist with a vision as total as Michael Jackson. … And yet when you look at both their lives, they were so destroyed by this desire to be God.”

The whole thing is excellent, filled with insights not only into the lives and careers of Baudelaire and MJ, but also into O’Grady’s own mind. (I particularly like her discussion of the actress Jeanne Duval , Baudelaire’s lover for 20 years and, for O’Grady, “the first postmodernist.”) And if you need any more incentive: today would have been Michael Jackson’s 56th birthday. A good time to listen to O’Grady discuss how he changed the world.

Malik Gaines, frieze, 2011

Malik Gaines, “Looking Back, Looking Forward.” Frieze Magazine, Issue 136, January-February, 2011. Published Dec. 12, 2010.

Gaines’s end-of-year review looks at Los Angeles and examines the blurring boundaries between art and entertainment. Its pointed commentary on The First and the Last of the Modernists’ image strategies was the most perceptive on the piece to date.

****

frieze asked a range of artists, critics and curators from around the world to choose what, and who, they felt to be the most significant shows and artists of 2010 and what they’re looking forward to in 2011

Malik Gaines

Curator at LAX ART, Los Angeles, USA and a member of the performance group My Barbarian.

It’s encouraging to look at Los Angeles, more than a decade after magazines were trumpeting its arrival as an ‘important’ art centre, and see a maturation of the ‘emerging artist’ class. Of course stalwarts such as Mike Kelley, Lari Pittman and Marnie Weber continue to shine. But impressive shows this year from Edgar Arceneaux, Alexandra Grant, Pearl C. Hsiung, Stanya Kahn, Yunhee Min, and many others suggest that an intelligent, technical young practice can evolve nicely over the long term, and that LA’s art culture has produced much more than a sensational moment; there is an art civilization here that feels durable. These artists are producing works that are great to look at, but that resist the encroaching spectacle culture.

This defence is now a necessity. While the LA art world has typically functioned in détente with Hollywood, the lines have blurred. Earlier in the year, University of California performance scholar Jennifer Doyle wrote good analyses (published on frieze.com) of Nao Bustamante on the television reality show Work of Art and James Franco’s and Kalup Linzy’s appearances on the daytime soap opera General Hospital. la moca’s complicity with the latter project drew attention to the institution’s Deitchification, which has been a mixed bag. Ryan Trecartin’s recent exhibition at the museum was impressive, mixing a YouTube sensibility with an inheritance of queer cinema and performance, while skillfully presenting the work as an immersive museum installation. There, the mode of entertainment occasionally produced awareness of generic structures and their logic, an effect that entertainment genres themselves only rarely propose.In showing Dennis Hopper with one hand while cancelling Jack Goldstein with the other, moca has also sent some disheartening messages in the last year. Despite contemporary LA’s difference from ’80s New York, one imagines the dissipated ghosts of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring lingering behind some choices, promoting an interest in popular forms that, for example, led to the insertion of a television dance instructor into the institution’s experimental ‘Engagement Party’ series. I’ve heard from a couple of people an idea that the popular approach is more populist; the notion that celebrities, clothes, and fun are for the people, while advanced art is for the elite. Others have argued that this socalled populism is really an elision with corporatism. While there are problems with the old-fashioned museum model, a legitimate fear is that the best parts of what museums do will be subsumed under a celebrity-commodity mandate. It’s clear that ‘celebritocracy’ is a poor form of government. California has produced two movie-star governors in the past decades – Ronald Reagan and the present incumbent, Arnold Schwarzenegger – and they have both been terrible. In politics, the danger is clear. (Need I mention a particular Alaskan politician who recently aired her own reality show?) In art, there can be reasons to entertain, to adapt entertainment forms and content. But let us hesitate before we lay ourselves out for consumption by the entertainment-postindustrial-complex.

A thoughtful approach to mass image production was offered by two wonderful works in the 2010 Whitney Biennial, by New York artists Danny McDonald and Lorraine O’Grady. Both use Michael Jackson as subject matter. In his kinetic assemblage, The Crossing: Passengers Must Pay a Toll In Order to Disembark (Michael Jackson, Charon, & Uncle Sam), (2009), McDonald has a Thriller-style Jackson doll presenting a giant penny in order to gain admission to the underworld, as Uncle Sam lays nearby, penniless and expired. O’Grady, in a series of portraits entitled ‘The First and the Last of the Modernists’ (2010), provides a map of Modernism’s dead-end, while addressing the ways that popular images produce categorical notions of race, age and life itself. In these pieces, the deceased star is used to interrogate the historical situation he symbolizes, reflecting back onto viewers a sense of the mechanics of our imposing image world, leaving this viewer with the insistent impression that there is still meaning to be had, even from such as this. Should I be offered my own television show, that’s the point I’ll try to make.

Two SITE Santa Fe reviews, 2011

Diane Armitage and Kathryn M Davis, “Agitated Histories at SITE Santa Fe.” In Critical Reflections, THE Magazine, p. 49, Dec./Jan. 2011/2012.

Two writers respond to the piece quite similarly from different points of view. In the “Critical Reflections” section of THE Magazine, and online at Visual Art Source.

****

Agitated Histories

Critical Reflections

SITE Santa Fe

1609 Paseo De Peralta, Santa Fe

By Diane Armitage

( . . . ) Some of the other projects in this group show are Lenny Bruce’s obscenity trial as revisioned by Eric Garduño and Matthew Rana; a documentary on the use of the Native American iconography as material for mascots that focuses on the well-known Santa Fe activist Charlene Teters; the exploitation of undocumented workers from South America in the video by Yoshua Okón; the resonance of past political speeches re-enacted against the backdrop of the 1970s Military Industrial Complex by Mark Tribe. There is also the odd resonance of strange historical pairings – such as Michael Jackson with Charles Baudelaire in Lorraine O’Grady’s work The First and Last of the Modernists (Charles and Michael); or the conceptual joining of the painter Francis Bacon with the comedienne Jackie “Moms” Mabley in a painting by Deborah Grant called Suicide Notes to the Self. These are all works that inflect the political subtexts in Agitated Histories with a subtlety of thinking that opens doors without necessarily drawing dogmatic conclusions. Even if there is a bit of a stretch required in conflating Michael Jackson’s essentially early-nineteenth-century romanticism with Baudelaire’s less dramatic intellectual deconstructions, there is no denying the oddness of O’Grady’s four diptychs, which function as prickly outer shells containing kernels, if not of truth exactly, then at least an interesting thought experiment. ( . . . )

Visual Art Source

Editorial: Features

“Agitated Histories”

at SITE Santa Fe, Santa Fe, New Mexico

Review by Kathryn M Davis

( . . . ) Perhaps this is a palimpsest of the whole: Many of the works look great on first glance, then cave in with the weight of their own content. Exceptions were Geof Oppenheimer’s “Anthem,” exposing as it does the homoeroticism of the military. Although I’m not sure that was the artist’s intended subtext, it adds layers of meaning to the video of an army band playing a jazzed-up mix of various patriotic marching songs. Lorraine O’Grady’s four large-scale photographs position, in diptych format, Charles Baudelaire and Michael Jackson as “The First and Last of the Modernists.” While the title could be argued up one theoretical side and down the other, the compositions are frankly lovely, even loving. Does “Agitated Histories” encourage change, or is it merely a string of storylines airing at the same time at full volume? If the latter is the case, I’ll take mine one episode at a time, please, so that I can focus on the content. ( . . . )

Francesco Bonami, 2010

Francesco Bonami Interview, vernissage.tv, “Whitney Biennial 2010.”

Transcript excerpt of a two-minute section from the 8-minute interview in which Francesco Bonami, chief curator of the 2010 Whitney Biennial, speaks about O’Grady’s piece and the room it shared with Bruce High Quality Foundation.

****

TRANSCRIPT: section 4:55-7:00 of Interview with Francesco Bonami (8:10), vernissage.tv.

Francesco Bonami: It’s not a huge show, it’s not the biggest show I ever curated, but maybe it’s the most important for me because it’s transformed me from an outsider when I came here 27 years ago into. . . I don’t want to say a true American, but into part of this big thing that is very strange to define, that is an American concept. . . part of “The American Dream.” It may be banal and a little bit soppy in sound. But for an outsider to curate the biennial of American art is a bit of a dream come true.

I can NOT pick a specific work, each work has a function in the show. I can pick a ROOM, the room on the fourth floor with Bruce High Quality Foundation, a group of artists that work collectively. They have this car with a film made of a patchwork of American images and with a text written by them on America as a lover. It is a love story without a happy ending.

And next. . . and in front of it, there is a work by the LEAST young artist in the show, Lorraine O’Grady, an Afro-American artist who makes a very interesting comparison between Michael Jackson and Charles Baudelaire, the French poet. . . looking at them as two fathers of different kinds of modernity—Baudelaire, for what is the Western world, and Michael Jackson, for pop culture and Afro-American culture in America—and yet, Lorraine O’Grady looks very young. The worlds of the two artists touch, become one thing, the past and the present become one thing.

I think this is a room that in some way summarizes the spirit of this exhibition.

18 Whitney Mentions, 2010

Various critics and bloggers, selected press on O’Grady in the 2010 Whitney Biennial, 2010.

A compilation of 18 selected and conflicting mentions of Lorraine O’Grady’s piece in the 2010 Whitney Biennial provides an opportunity to compare responses to The First and the Last of the Modernists and parse their differences.

****

1.

“Lorraine O’Grady’s stunning photo diptychs of Charles Baudelaire with Michael Jackson restore MJ to majesty and the Bruce High Quality Foundation’s 1960s style motion picture about the ambiguity of trying to love America, projected on the windshield of a white ambulance, has a depth of mournful feeling that wil make you weep.”

Charlie Finch, “A Room of One’s Own.” Review of the Whitney Biennial, Artnet.com, February 24, 2010.

2.

“You think, ‘What’s going on here?’ And that’s a question art should raise.

“At a certain point the curators seem to pose it, critically, about new art in general. In a fourth-floor gallery next to the one filled with abstract paintings they’ve placed a photographic piece by the conceptual artist Lorraine O’Grady. Titled “The First and Last of the Modernists,” it pairs portraits of Charles Baudelaire (he looks like Charles Manson in one) and Michael Jackson, raising issues of race, class and the highly ambivalent nature of beauty that the new abstraction ignores.

“Ms. O’Grady’s work, with roots in the black art and feminist movements of the 1960s and ’70s, was overlooked until fairly recently, probably because it’s hard to pin down as far as meaning and attitude. And it makes sense that she shares space in the show with some category-dodging younger contemporaries, the five artists who make up the collective called the Bruce High Quality Foundation.”

Holland Cotter, “At a Biennial on a Budget, Tweaking and Provoking.” New York Times, February 25, 2010, p C21.

3.

“While neither Lorraine O’Grady nor Ania Soliman might usually be considered a “photographer”, both are using the recontextualization of appropriated photographic imagery as the basis for the art included in this show. O’Grady’s works juxtapose found images of Charles Baudelaire and Michael Jackson in varying color tones, wryly commenting on the ups and downs of celebrity. Soliman layers a wide range of found images of pineapples into a photomontage alphabet stuck directly to the wall, merging text and photographs into a hybrid historical survey reminiscent of Dada collages. With these examples, it is clear that we have moved beyond the irony of simple appropriation/mashup and on to more complicated and conceptual combinations of images with social/political overtones.”

DLK Collection, “Whitney Biennial 2010,” April 20, 2010.

4.

“People–art’s favorite subject–are not beautiful in this exhibit. They are distorted and injured here.

“Stephanie Sinclair‘s gruesome photos show Afghani women who survived self-immolation. Lorraine O’Grady‘s portrait of Dorian Grey-like photos pair Charles Baudelaire and Michael Jackson as they age. Michael Jackson’s transformation from beautiful young African-American man to the whitened melting flesh of a white-woman-wanna-be is devastating. Baudelaire, for all his own issues, holds up a lot better over time. The themes of grotesque humanity come out in Storm Tharp’s drawings, Nina Berman’s family-album-like photos and Jessica Jackson Hutchins’ ceramic body parts on a sofa.”

Roberta Fallon and Libby Rosof, The Artblog. By Libby, “Shiny penny no more—Whitney Biennial takes on the new America.”

5.

“What am I getting myself into?” I wondered as I approached the Whitney’s inverted facade. Having read a mixture of reviews of the show, some scathing and some packed with praise, I felt nervous. This was my first Biennial. Usually the shows I frequent center on a certain theme, context, time period, or artist. Here, though, I would only be seeing the “now” of the art world ( . . . )

“I had kept Baudelaire’s The Painter of Modern Life in mind as a sort of lens by which to read what would be assembled to represent these last two years. I know that might seem like an irrelevant source, being published in 1863 and all, but I was soon to find out that one of the works shown was making similar use of Baudelaire’s modernity. Lorraine O’Grady’s The First and the Last of the Modernists is a series of diptychs consisting of paired photographs of Michael Jackson and Charles Baudelaire at similar ages and points in their careers. O’Grady’s series of paired portraits aims to guide us through each cultural figure’s journey, the height of their innovations in relation to modern culture, and the cost of these things on their personal lives. The champion of modernity was side by side with the king of pop and the feeling this gave me was quite an unsettling one.”

Amanda McCleod, “National Treasure: In Which It Only Happens Once Every Two Years.”

6.

“‘The First and Last of the Modernists’ encapsulates culture with four simple pictures of Baudelaire juxtaposed with Michael Jackson. The work makes a sweeping assumption about wealth, fame, and artistic ambition. I really like this kind of ballsy sweep, which according to the label copy, took sorting through thousands of Jackson images to match the scarce Baudelaire images O’Grady had on hand.”

Dan Boehl, “Armory, Volta, Biennial: The Best Things.” ( . . . ) might be good, issue 143, March 12, 2010.

( . . . )

El Pais, Madrid, 2010

Barbara Celis, Whitney Biennial review, Diario El País, Madrid, 2010.

Original Spanish, plus English translation, of article in Spain’s equivalent to the New York Times. The review contains a fuller-than-usual discussion of the significance of O’Grady’s installation.

****

[translated from Spanish]

A More Female and More Discreet Whitney Biennial. . . Museum reduces number of artists by half this year.

The age of art-as-spectacle is over. With the economy gripping the heels of institutions, galleries and creative talents, it seems reasonable that the Whitney Museum of New York would this year put on a Biennial with half the artists of recent years (55) and, above all, with a profile both discreet and unpretentious. The 75th edition of the Whitney Biennial (through May 30), titled succinctly 2010, does nonetheless provide a headline for those in need of one: it is the first in history with a female majority. And this becomes even more patently obvious on the museum’s top floor, where the retrospective Collecting Biennials has been installed. The best of each decade is set out there, from Rauschenberg to Andy Warhol and Jasper Johns, but the female names are almost anecdotal — Eva Hesse, Cindy Sherman and few others.

However, on the three floors occupied by the Biennial proper, there are a great many works made by women and, surprisingly, these are neither feminist art nor odes to extreme youth – as occurred throughout the last decade. Rather, the great majority of the artists are over 40, including one approaching 76, Lorraine O’Grady, relatively ignored up to now, who has finally found recognition. Her work, The First and the Last of the Modernists, is a disturbing display of photographs of the singer Michael Jackson and the poet Baudelaire at different stages of their existence, but organized by age and paired, so that one can see the evolution and transformation of both icons, whose lives had a certain parallelism, however incredible this might seem.

It is surprising to find two photographic series, which in a different context would be called photo-journalism but that the curators have decided to include in the Biennial, thus blurring a bit further the limits of what can be defined as art. The prize-winning Stephanie Sinclair occupies three walls with horrifying photographs of Afghanian women who have self-immolated in protest against abusive treatment by their husbands. The images, showing the absolute vulnerability of the victims as they appear semi-nude, burnt, bloody, in sordid hospital waiting rooms, are a fist-punch to the conscience of the visitor. In another room, Nina Berman’s disquieting photographs document the life of marine Ty Ziegel, completely disfigured during the Iraq war. The images show him after his return home with even his wedding to his high-school sweetheart, though everything in the images preannounces that the marriage will not end well.

It’s strange to find several rooms dedicated solely to painting, a genre that almost seemed exiled from previous Biennials. There is an immense space devoted to watercolors by Charles Ray, and another room in which tiny oils by Maureen Gallace are hung beside Julia Fish’s abstract works. There are also numerous video installations. Some are playful, like Marianne Vitale’s Welcome to the Future of Neutralism, which uses verbal and aesthetic references taken from the early avant-guards so as to ironize the idea of power. Also in an ironic vein is Kate Gilmore’s video Standing Here, whose nature – a woman with high-heels trying to break out of a cubicle by kicking it – provokes an incredulous smile.