Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline

Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline, O’Grady’s second performance, premiered at Just Above Midtown Gallery on October 31, 1980. In an unexpected turn of events, just one month after Mlle Bourgeoise Noire’s invasion of the avant-garde gallery protesting the timidity of its artists, Linda Goode Bryant, the gallery’s visionary founder-director, had invited O’Grady to represent JAM in Dialogues, an exhibit she was creating to showcase nearly a dozen downtown alternative art spaces. The exhibit would feature a performance series.

O’Grady accepted JAM’s invitation, but the new occasion was fundamentally different than Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, the performance announcing her to the art world, and felt a bit alien to her more radical Dadaist intentions. Rather than a self-motivated, unexpected guerrilla invasion, the new piece would be commissioned for a paying audience seated expectantly in chairs. Interestingly, her response to such situations would be similar throughout her career, an increased emphasis on the personal over the political element, though both would always be there. In this case, unlike the joyful anger motivating Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, the new work would be characterized by somber but still critical mourning in a memorial to her deceased older sister, Devonia Evangeline.

The new performance examined the difficult relationship of O’Grady and her sibling via historic comparison to similarly troubled sisters, Nefertiti and the younger Mutnedjmet. Through subject matter that was intensely personal, she also addressed political targets such as doomed attempts to identify with “African” cultures and to resurrect their rituals then current in certain strains of African-American art. At the same time, she also critiqued the undoubted racism of Egyptology as a discipline. O’Grady was hardly a trained actress or dramatist, but the period’s open performance aesthetic enabled her “writing in space” to express ideas she would otherwise not attain.

Email Q & A w Courtney Baker (N/DE), 1998

Lorraine O’Grady Interview by Courtney Baker, Ph.D. candidate, Literature Program, Duke University.

Unpublished email exchange, 1998

The most comprehensive and focused interview of O’Grady to date, this Q & A by a Duke University doctoral candidate benefited from the slowness of the email format, the African American feminist scholar’s deep familiarity with O’Grady’s work, and their personal friendship.

****

( . . . ) Q: Re: Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline—In pairing images of Devonia with images of Queen Nefertiti were you trying to say something about class? You mentioned in an interview that you were criticized (or feared being criticized) for equating your (sister’s) family with royalty.

A: Well, of course, I was. In the beginning, I was always trying to say something about class. In those days, pre-Jeffersons, pre-Cosby, it’s hard to imagine how invisible the existence of class was. But luckily I was also talking about other things, or the images wouldn’t continue to live. The deepest motivation for N/DE was my desire to say something about sibling rivalry and its obverse, hero worship, and the ways in which both are affected by death. Then there was my usual need to critique Western art history (here, sub-division: Egyptology). It was another of my overdetermined art pieces. But without those uncanny resemblances, I don’t think I could/would have said anything.

At one level, I’d been as frustrated by the teacher pointing to the map of Africa and saying, “Children, this is Africa, all except this, and this is the Middle East,” as the next black kid. So to that extent, the piece was Afrocentric.

But even the most cursory glance at Egyptian culture (the structure of kingship, religion, etc.) is enough to convince one of, at the least, an African substratum. The denial of this is on the level of white historians’ refusal to entertain evidence for Thomas Jefferson fathering Sally Hemings’ kids—you are not dealing with rationality here. Nevertheless, it was annoying to have my work lumped with simplistic Afrocentric arguments: i.e., lineage as some sort of ridiculous salvation rather than as a sign of complexity.

I have often thought that if I’d come across a family photo album in a flea market with equally remarkable resemblances to my own family, it would have sparked my imagination just as well.

But that itself raises a set of interesting questions: How might such a found album have come into being? Where might it have come from? What would the family’s racial composition and class have been? If, as I believe, we do inhabit a world where hybridity is a norm, then the family setting off those resemblances could as easily have been a white as a black one. But the class question is a bit more tricky. While it needn’t have been royal or even aristocratic, I think it would have required a sophisticated family to produce responses so intense. Comparisons with a working-class or peasant family too easily might have become academic in the worst way.

( . . . )

Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline, 1997

“Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline,” in College Art Association, Art Journal, Winter 1997, Vol 56, No 4: Performance Art: (Some) Theory and (Selected) Practice at the end of this Century, pp 64-65. Guest editor, Martha Wilson.

© Lorraine O’Grady

In this article for Art Journal, Winter 1997, the special issue on performance edited by Martha Wilson, O’Grady focuses first on Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline, then discusses its relationship to Miscegenated Family Album, alluding to the advantages and disadvantages of the move from performance to photo installation.

****

( . . . ) In 1980, when I first began performing, I was a purist – or perhaps I was simply naive. My performance ideal at that time was “hit-and-run,” the guerilla-like disruption of an event-in-progress, an electric jolt that would bring a strong response, positive or negative. But whether I was doing Mlle Bourgeoise Noire at a downtown opening or Art Is . . . before a million people in Harlem’s Afro-American Day parade, as the initiator, I was free: I did not have an “audience” to please.

The first time I was asked to perform for an audience who would actually pay (at Just Above Midtown Gallery, New York, in the Dialogues series, 1980) – I was non-plused. I was not an entertainer! The performance ethos of the time was equally naive: entertaining the audience was not a primary concern. After all, wasn’t it about contributing to the dialogue of art and not about building a career? I prepared Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline in expectation of a one-night stand before about fifty cognoscenti and friends. It was a chance to experiment and explore. Performance’s advantage over fiction was its ability to combine linear storytelling with nonlinear visuals. You could make narratives in space as well as in time, and that was a boon for the story I had to tell.

My older sister, Devonia, had died just weeks after we’d got back together, following years of anger and not speaking. Two years after her unanticipated death, I was in Egypt. It was an old habit of mine, hopping boats and planes. But this escape had turned out unexpectedly. In Cairo in my twenties, I found myself surrounded for the first time by people who looked like me. This is something most people may take for granted, but it hadn’t happened to me earlier, in either Boston or Harlem. Here on the streets of Cairo, the loss of my only sibling was being confounded with the image of a larger family gained. When I returned to the States, I began painstakingly researching Ancient Egypt, especially the Amarna period of Nefertiti and Akhenaton. I had always thought Devonia looked like Nefertiti, but as I read and looked, I found narrative and visual resemblances throughout both families.

Though the invitation to perform before a seated audience at Just Above Midtown was initially disconcerting, I soon converted it into a chance to objectify my relationship to Dee by comparing it to one I could imagine as equally troubled: that of Nefertiti and her younger sister, Mutnedjmet. No doubt this was a personal endeavor, I was seeking a catharsis. The piece interwove partly subjective spoken narrative with double slide-projections of the two families. To the degree that the audience entered my consideration, I hoped to say something about the persistent nature of sibling relations and the limits of art as a means of reconciliation. There would be subsidiary points as well: on hybridism, elegance in black art and Egyptology’s continued racism.

Some people found the performance beautiful. But to tell the truth, few were sure of what I was up to. Nineteen eighty was seven years before the publication of Martin Bernal’s Black Athena, and a decade before “museumology” and “appropriation” reached their apex. As one critic later said to me, in 1980 I was the only one who could vouch for my images. I will always be grateful to performance for providing me the freedom and safety to work through my ideas; I had the advantage of being able to look forward, instead of glancing over my shoulder at the audience, the critics, or even art history.

Performance would soon become institutionalized, with pressure on artists to have a repertoire of pieces that could be repeated and advertised. I would perform Nefertiti several more times before retiring it in 1989. And in 1994, now subject to the exigencies of a market that required objects, I took about one-fifth of the original 65 diptychs and created a wall installation of framed Cibachromes. Oddly, rather than traducing the original performance idea, Miscegenated Family Album seemed to carry it to a new and inevitable form, one that I call “spatial narrative.” With the passage of time, the piece has found a broad and comprehending audience.

The translation to the wall did involve a sacrifice. Now Miscegenated Family Album, an installation in which each diptych must contribute to the whole, faces a new set of problems, those of the gallery exhibit career. The installation is a total experience. But whenever diptychs are shown or reproduced separately, as they often must be, it is difficult to maintain and convey the narrative, or performance, idea. As someone whom performance permitted to become a writer in space, that feels like a loss to me.

Thoughts on Diaspora and Hybridity (N/DE), 1994

“Thoughts on Diaspora and Hybridity.” Unpublished lecture at Wellesley College delivered to the Wellesley Round Table faculty symposium on Miscegenated Family Album.

© Lorraine O’Grady 1994

Written shortly after the “Postscript” to “Olympia’s Maid,” this lecture delivered to the Wellesley Round Table, a faculty symposium on Miscegenated Family Album, takes a retrospective look at O’Grady’s earlier life and work through the prism of cultural theory.

****

( . . . ) For me, art is part of a project of finding equilibrium, of becoming whole. Like many bi- or tri-cultural artists, I have been drawn to the diptych or multiple, where much of the information happens in the space between, and like many, I have done performance and installation work where traces of the process are left behind.

The new prism of diaspora-hybridity helped me see that the hybridized form and content of Miscegenated Family Album was symptomatic of larger forces just coming into focus in the culture as a whole. Though I had been operating primarily out of personal compulsion (to resolve a conflicted relationship with my dead sister) and the aesthetic necessities of the work, it contained what Edward Said in Imperialism and Culture (1993) called “overlapping territories and intertwined histories.”

Miscegenated Family Album, the installation which is premiering now, is in fact extracted from an earlier performance, Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline, which I did in 1980. Both pieces have benefited from the fact that, since 1980, the work of post-colonialist thinkers such as Said, Homi Bhabha, Paul Gilroy, Gayatri Spivak, and Trinh Minh-ha has shown that our old idea of ethnicities and national cultures as self-contained units has become in an era when “There is a Third World in every First World, and vice versa.” In fact, we were never, even in situations of the most extreme brutality, hermetically sealed off from each other. This realization, marked out in cultural studies, has been paralleled in contemporary art with an additional understanding: that the intellectual, emotional and political factors from which art is made have themselves not been segregated. We do not look at or produce art with aesthetics and philosophy over here, and politics and economics over there.

In fact, as these false barriers fall, we find ourselves in a space where more and more the entrenched academic disciplines appear inadequate to deal with the experience of racially and imperially marginalized peoples. Perhaps the only vantage point from which the center and the peripheries might be seen in something approaching their totality may be that of exile, or diaspora. As the 21st century approaches, we could be facing a prolonged period of intellectual revisionism. Perhaps all of us, the newly de-centered as well as the already marginal, will have to adopt (in the spirit of DuBois’s old theory of “double consciousness”) what Gilroy has called “the bifocal, bilingual, stereophonic habits of hybridity.”

( . . . )

Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline was the 1980 performance from which I later developed Miscegenated Family Album. It was an early attempt to treat these ideas in terms of my personal background. Of course, the performance wasn’t created in an emotional and intellectual vacuum: it was a working through of a troubled, complex relationship with my dead sister, Devonia, a relationship that ran the gamut from sibling rivalry to hero worship and was itself a sort of hybrid.

The performance functioned on a lot of levels. On one level, that of a certain emotional distance, it dealt with the continuity of species experience—the old plus ça change, c’est plus la même chose, or the more things the more they stay the same. While this idea might appear essentialist on the surface, I don’t feel there is any necessary conflict between permanence and change. To me, the continuity reflected in the piece’s dual images was a kind of geological substratum underlying what was in fact a drastic structural diversity caused by two very different histories. The similarities in the two women’s physical and social attitudes didn’t negate the fact that Nefertiti had been born a queen and Devonia’s past included slavery. The performance was not “universalist” in the current sense of the term.

My ability to think the two women, ancient and modern, in the same space came most immediately out of an experience I had in Egypt in the early 60s. On the streets of Cairo, I’d been stunned to find myself surrounded by people who looked like me, and who thought I looked like them. That had never before happened to me, either in Boston where I was raised, or in Harlem, where I used to visit my godparents. All my life I had noted a resemblance between Devonia and Nefertiti. But in Cairo, I’d been jolted into an intuition of what that resemblance might be based on.

When I returned to the States, I began an amateur study of Egyptology. Of course, without the benefit of Martin Bernal’s Black Athena, not published until 1987, I was really reinventing the wheel. I soon came to feel that many of Ancient Egypt’s primary structures—the dual soul, its king who was both god and man, the magic power invested in the Word, a particular concept of justice or maat, as well as its seemingly unique forms of representation—were, in fact, refractions of typically African systems. I could detect a ghostly image. . . a common trunk, off which different African cultures, north and south, east and west, had branched. It was significant that the heroic period of Egyptian culture, the one that created the Egypt of our minds—that of the pyramids and hieroglyphic writing—came during the first four dynasties at Thebes in the southern, “African,” part of Egypt. And yet traditional Egyptology with few exceptions, such as the works of Henri Frankfort and E. A. Wallis Budge, had voluntarily impoverished itself by not exploring the possibility of an African origin for these taxonomically “difficult” structures, whose forms may have further hybridized with intercultural contact. Instead, the discipline in the 60s and 70s continued trying to fit Egyptian culture into the “round hole” of the Near East. There seemed, on the part of most, to be an almost magical insistence that the cataracts of the Nile were somehow a more impassable barrier than the Alps or the Pyrenees.

I should also say that there is no need, on the opposite side of the debate, for the unscholarly claim that Cleopatra was black. Like all the Ptolemies, the line of pharoahs imposed by Alexander the Great in Egypt’s waning years, Cleopatra was Greek. But 300 years of Greek Ptolemies could have little effect on the “African-ness” of three millennia of Ancient Egyptian culture, including the dynasty of Akhenaton and Nefertiti a thousand years before Alexander’s death blow. One of the concepts that enabled my use of historic imagery in Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline and the later Miscegenated Family Album was my suspicion that, like some ancient Cuba, Egypt had been hybrid racially. . . but, culturally, had been aboriginally black. Given the abysmal state of ( . . . )

Interview by Linda Montano (N/DE), 1986

Interview. In Linda Montano, Performance Artists Talking in the Eighties: Sex, Food, Money/Fame, Ritual/Death, University of California Press, Berkeley. Based on 1986 interview.

June 1986*

Montano’s questions on “ritual” cast interesting light on the connection between O’Grady’s early life and her performances. The unedited transcript of the interview contains answers in greater depth on Mlle Bourgeoise Noire and Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline.

( . . . ) Montano: How did the character [of Mlle Bourgeoise Noire] progress?

O’Grady: ( . . . ) The appearance at the New Museum and the one at JAM were alike in that they were guerrilla actions in which, uninvited and unexpected, she invaded a space to give a message that presumably would be painful to hear. I will always admire Linda Bryant, JAM’s “black bourgeois” founder-director, for not only listening, but receiving thoughtfully my criticism of an activity she was deeply involved in.

Only two months after Mlle. Bourgeoise Noire’s invasion of Bryant’s space, I was invited to represent JAM as the performance artist in a show called Dialogue. I’ve been interested in Egyptology for a long time, and coincidentally, the day the call from Linda came, I had just bought a book called Nefertiti. When she asked what I would do as a performance, I looked at the book in my hand and said, never having thought of it previously “I’m going to do a piece called Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline.” Devonia Evangeline was my sister’s name, and the piece would be about her death as the result of an abortion, so the piece had feminist overtones. But for me its main political import was the placing of images on the screen that focused on the physical resemblances of a black American and an ancient Egyptian family. Egyptology has always been such a racist discipline. Because of Western European attitudes and policies, so ingrained a to be hardly thought-out, ancient Egypt has always been denied as belonging to Africa. For instance, I will never forget that when I was a little girl in the third grade in the early forties in one of those old-fashioned schools where the maps got pulled down over the blackboards during the geography lessons, when we had our lesson on Africa and the teacher pulled down the map and pointed at it to our class of twenty-five kids, all but two or three of whom were white, she said quite blithely and unreflectively, “Children, this is Africa except for this”—the long wooden pointer touched Egypt. “This is Egypt,” she said, “and it isn’t in Africa but in the Middle East.” The worst of it is that this is the way Egypt has always been presented, even at the most sophisticated museum levels. It has only really been since the sixties and the breakup of the empire, combined with the knowledge explosion, that there has been something of a revision of imperialist intellectual attitudes, but it takes generations to get an idea out of currency. Even now, when I did this performance in the eighties, it was revolutionary and, perhaps, arrogant to put those images up on the screen. Putting a picture of Nefertiti beside my sister was a political action.

Montano: And that performance was an action by Mlle. Bourgeoise Noire?

O’Grady: I wasn’t aware of it at the time. It wasn’t until a few years later that I began to realize that everything I did in art was done by her. ( … )

Ancient Art Podcast (N/DE), 2009

Lucas Livingston, “Episode 22: Nefertiti, Devonia, Michael.” Transcript. Ancient Art Podcast, July 6, 2009.

Complete transcript of podcast by Lucas Livingston, an Egyptologist associated with the Art Institute of Chicago, which discusses Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline and Miscegenated Family Album in detail. Also a YouTube video with high-quality images.

****

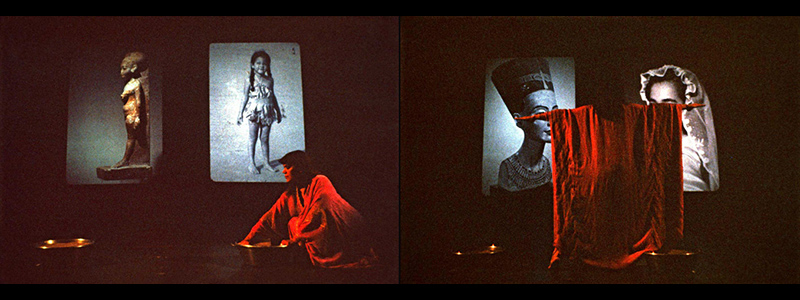

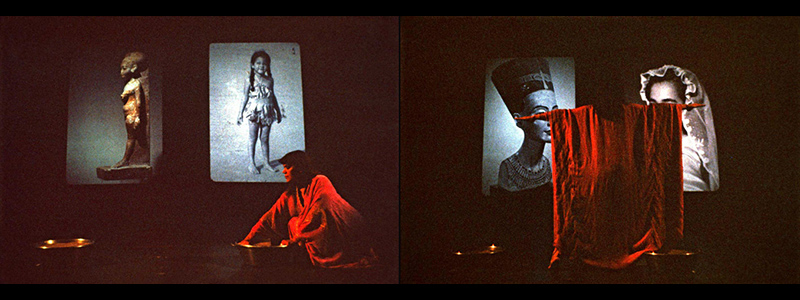

Transcript On October 31, 1980 at Just Above Midtown Gallery in New York City, artist Lorraine O’Grady, dressed in a long red robe, debuted her new work of performance art. On a dark stage with a slideshow backdrop and dramatic recorded narration, O’Grady enacted hypnotic, ritualized motions, like the priestess of an ancient mystery cult, incanting magicks over vessels of sacred sand and offerings blessings of protection to the projected images of the Ancient Egyptian Queen Nefertiti and her late sister Devonia Evangeline O’Grady Allen. In the piece entitled Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline, Lorraine O’Grady confronted her relationship with her sister through the lens of Nefertiti and Nefertiti’s own apparent sister, Mutnedjmet — a relationship which O’Grady felt would have been equally troubled. O’Grady’s sister Devonia tragically died just a few short weeks after the two of them had finally begun speaking after many years of a strained relationship.

Inspired two years later after a trip to Egypt, O’Grady began researching Queen Nefertiti and her famed family of the Amarna Period. While in Egypt, O’Grady encountered a new found feeling of belonging — as the artist says in her own words, “surrounded for the first time by people who looked like me” (Art Journal 56:4, Winter 1997, p. 64). Of African, Caribbean, and Irish descent, O’Grady never felt a similar sense of kinship in her homes of Boston and Harlem. In a New York Times article from September 26, 2008, “she remembers her youthful efforts to balance what she has called her family’s ‘tropical middle-and-upper class British colonial values’ with the Yankee, Irish-American and African-American cultures around her.” Building on a resemblance that she long thought her sister had with Nefertiti, she was struck by what she saw as narrative and visual resemblances throughout both families. While pairing members of her own family with those of Nefertiti, O’Grady weaves together various narratives connecting personal stories with historical events (Alexander Gray Associates press release, 10 Sep 2008).

In 1994, from the performance piece Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline originally composed of 65 photographic comparisons, O’Grady took about a fifth of the diptychs and framed them in an installation piece entitled Miscegenated Family Album, which has been exhibited in various galleries, including the Art Institute of Chicago in 2008. O’Grady’s work often focuses on black female identity and subjectivity, as well as cultural and ethnic hybridization. Miscegenation, in the title of the piece, is the procreation between members of different races, which was still illegal in much of the US as late as 1967, when it was finally overturned by the Supreme Court.

The ethnic identities of Nefertiti and Akhenaten have been debated in the spheres of Egyptology and African studies, with no immediate end in sight. Not quite as much as Cleopatra, but still. In Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline and Miscegenated Family Album, O’Grady directly confronts the racism of a white-dominated, Western-European interpretation to the field of Egyptology. While the notion of a black African cultural and ethnic influence on Ancient Egypt is frequently discussed today, we should bear in mind that in 1980, when O’Grady first performed Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline, this was still seven years before the publication of Martin Bernal’s highly acclaimed and criticized work Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization.

Now, I’m not saying that the sub-Saharan African influence on Egyptian civilization is definitively confirmed. It’s still a hotly debated issue with many shades of gray. Ancient Egypt was a ( . . . )

Nick Mauss in Artforum (N/DE), 2009

Nick Mauss, “The Poem Will Resemble You: The Art of Lorraine O’Grady.” Artforum Magazine, vol. XLVII, no. 9, pp. 184-189, May 2009.

Mauss’s article for Artforum is, with Wilson’s INTAR catalogue essay, one of the most extended and authoritative pieces on O’Grady’s oeuvre to date. It was one-half of a two-article feature that also included O’Grady’s artist portfolio for The Black and White Show.

****

( . . . ) “I confess, in my work I keep trying to yoke together my underlying concerns as a member of the human species with my concerns as a woman and black in America. It’s hard, and sometimes the work splits in two—within a single piece, or between pieces. But I keep trying, because I don’t see how history can be divorced from ontogeny and still produce meaningful political solutions”.

( . . . )

One month after Mlle Bourgeoise Noire’s invasion of Just Above Midtown, O’Grady was invited by the gallery’s founder-director, Linda Goode Bryant, to participate in a performance showcase called “Dialogues.” O’Grady’s contribution, Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline, 1980, juxtaposed the story of her relationship to her estranged sister, Devonia, with a chronicle of Nefertiti’s relationship to her younger sister, Mutnedjmet. The first part of the performance consisted of side-by-side projections of slides of Nefertiti and Devonia and their families, set to a sound track that narrated the stories of the women’s lives, one from a historical point of view, the other from the point of view of the little sister (O’Grady). The progression of slide pairings activated a flickering of resemblance and dissemblance, thanks to the often uncanny similitude between the projected faces or the noble poses and the contrast or correlation between the trajectories of the title characters’ lives. “They die at the ages of thirty-seven and thirty eight respectively,” O’Grady later explained, “Nefertiti in 1344 BC after a banishment of six years, and Devonia in 1962 from the complications of an illegal abortion. The screens contain sarcophagi with lifted lids.”

In the second part of the performance, O’Grady herself came onstage wearing a red caftan and attempted to enact the narrator’s directions for the ancient-Egyptian Opening of the Mouth ceremony, the last ritual before burial, whose function was to free the deceased for a full afterlife. O’Grady’s demonstrative struggle and failure to fulfill the commands of the tape-recorded voice pronounced the hope for and ultimate ineffectuality of reconciliation through art. As images of the two “sisters” reappeared on the screen, O’Grady approached the projected faces and struck their mouths with an adze as the tape proclaimed, “Hail, Osiris! I have opened your mouth for you. I have opened your two eyes for you.” If, as O’Grady recounts, many members of the audience perceived the juxtaposition of her own middle-class family with ancient-Egyptian royalty as arrogant, their verdict missed the greater provocation of her conceptual linking. In an interview with Linda Montano, O’Grady states, “Putting a picture of Nefertiti beside my sister was a political action.” Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline enacted legitimate pain in a complicated work of mourning, triangulating between the present and two irretrievable pasts. ( . . . )

Judith Wilson (N/DE), 1991

Judith Wilson, Lorraine O’Grady—Critical Interventions, INTAR Gallery, New York, 1991.

( . . . ) Further Adventures: From the Nile Valley to 125th Street. . . and Back Again. . .

Four months later, when O’Grady performed next at JAM, she unveiled a work completely unlike the one in which she had made her debut. Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline was a departure in almost every conceivable way. Where the tone of Mlle Bourgeoise Noire had been caustically satirical, the new piece was elegiac. Where the first work had lampooned Black aesthetics in the 1980s by linking them with social conventions of the 1950s, the new work lamented the tragic fates of an ancient Egyptian queen and a modern African-American “princess.” Where the earlier piece had smudged the line between life and art by utilizing “real” space/time and inviting a degree of audience participation, the new performance operated in the symbolic arena and mythic time of ritual, and re-established conventional boundaries between the artist/performer and her spectators.

But even more than Mlle Bourgeoise Noire — with its Caribbean beauty contest (a reference to O’Grady’s West Indian ancestry) and its send-up of Black bourgeois proprieties —, the current piece contained autobiographical elements. Devonia Evangeline was the artist’s elder sister, a woman whose fairy tale life came to a shockingly sudden end at age 38. The performance consisted of images of the artist’s late sibling and other family members, which were projected alongside images of the Egyptian queen who had died at age 37 and members of her family, while O’Grady’s taped voice delivered an elliptical account of both women’s lives. Finally, stationed in front of the giant heads of Nefertiti and Devonia Evangeline that were being beamed on the wall, O’Grady enacted a ritual prescribed by the Egyptian Book of the Dead. “Hail, Osiris! I have opened your mouth for you, I have opened your two eyes for you\,” the artist chanted. With these words, she donned a mantle even denser with symbolism than Mlle Bourgeoise Noire’s white-glove-laden cape.

On the one hand, while the ritual she invoked was meant to insure the deceased’s immortality, her rendition underscored the futility of such gestures. On the other, by drawing the viewer’s attention to the uncanny parallels between the facial features and poses of O’Grady’s relatives and ancient Egyptian royalty, the artist simultaneously drove several controversial points home. Ancient Egypt’s African heritage, Black America’s multi-racial ancestry, and the existence of a pre-Cosby era African-American aristocracy were all visibly evidenced by the juxtaposed photographic imagery. Thus, while she failed to restore her lost sister to sight and breath, O’Grady succeeded in giving voice to the stifled history of a great civilization, and opening our eyes to a seldom seen aspect of a people, as well as a virtually unknown social class.

A further component of Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline and an especially crucial one was its frank exposure of the highly volatile and visceral attachments between femaie relatives — sisters, mothers and daughters. In some ways, the work can be seen as the artist’s attempt to resolve conflicts left suspended in the wake of her sister’s sudden death. But insofar as Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline blends female autobiography with ceremony and history, it can be seen as a step in the direction of her next major theme — what she has called “Black female self-reclamation.”

( . . . )

LIVE performance 5, 1980/81

Patricia Jones, “‘Dialogues’: Just Above Midtown Gallery (October),” LIVE: performance 5, Performing Arts Journal, Inc., pp. 33-35, New York, 1981.

Patricia S. Jones discusses a downtown gallery performance series at Just Above Midtown, NYC, Oct 1980 in a late 70s-early 80s annual journal. Article makes special note of O’Grady’s first performance of Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline.

****

Although JAM/Downtown, a Tribeca alternative arts center, attempted to bring together the diverse and divergent groups that make up the “downtown” just-out-of-the-mainstream part of the art world, few of the participants made use of the theme — “Dialogues.” The performances presented were for the most part “monologues” with passive audience participation.

The lack of communication was most apparent on the program that featured a poet, Native-American dancers/storytellers, a fiber artist and a visual artist. The evening began with great promise. At the door, funny sunglasses were sold for about a dollar and once they were on the faces of the purchasers, the audience looked like a campy photograph of people waiting to see a 3-D movie. After a long wait, the program began with Roberto Ortiz-Melendez. He sat down in the large white space and read a catalogue of wrongs without a whiff of originality of thought.

“Echoes of the Past and Present,” performed by Marie Antoinette Rodgers and Jane Lind, concerned stories of suffering and death as well as affirmations of Native American culture and eminence. Despite the powerful themes, the piece seemed insincere and ill-conceived. ( . . . )

Halloween brought out a large and curious crowd of costumed fun seekers as well as friends and fans of the performers. The mood was festive but the pieces were mostly serious, a couple very melancholy. John Malpede — who has the face of a Wendell Corey-type B-movie actor — performed “Too Much Pressure” [see photo]. His deadpan delivery, choice of music, and arch storytelling did center on the dialogue theme. Mostly, his response was to speak of the futility of communication by centering on the manifestations of those afflicted with “hebephrenic schizophrenia”; i.e., laughing when it is most inappropriate. The laughter arises because “the hebephrenic regards the very fact of communication ludicrous and ridiculous.” As Malpede stalked in front of an overstuffed easy chair, he gave three versions of a terrifying story of patriarchal manipulation. His piece, despite its brevity, questioned not only the value of communication but the necessity of the family, of ambition, philosophy and art.

Lorraine O’Grady’s “Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline” followed. Nefertiti means “the beautiful one has come”; Devonia Evangeline was O’Grady’s sister [see photo]. That phrase resonated throughout her piece which connected two women of African descent separated by history, geography, and circumstance. Despite its slow pacing, it filled the space visually and aurally; the slides and the taped narration fused the lives of two women — who both died at 38 under tragic circumstances — through stories about weddings, sibling rivalries, childbirths, breakdowns, deaths. What one learned about Evangeline was that she was loved to death; Nefertiti was hated to death. And yet their deaths were so similar in tone that, in the final analysis, they died because they wanted to change their status as women, as members of the family.

The piece became most evocative when O’Grady stood before the large slide and attempted to resurrect her sister by performing a ritual found in the Egyptian Book of the Dead, but to no purpose. The ultimate passivity of the dead seemed galling to the righteous determination of the living. Then slides show the daughters of the women — the beautiful ones! Like Ishmael Reed in his novels Mumbo Jumbo and Yellow Back Radio Brokedown, O’Grady uses Egyptian motifs to enhance and explicate the imaginative lives of Afro-Americans.

Unfortunately, Annie Hamburger’s piece followed this one. Too long, too slow, ill-conceived. Hamburger is no slouch as a performer. She had a great presence and her props were interesting, but one never knew just why she was mouthing the words she was saying and moving about. expressive gestures were not enough, particularly after Malpede and O’Grady.

The final performance was Stuart Sherman’s spectacle, “The Erotic.” Here was a kind of Groucho Marx whiz kid whipping out objects with the agility of a Sufi master. The juxtapositions of objects often took on a surreal and unnerving sensibility. At other times, they seemed ludicrous. Sherman was affable throughout, keeping up the patter of tiny objects and engaging the audience. The piece seemed meditative in an odd way and tangential to the theme. For me it was anything but erotic. The objects were too smooth, too diffident, too cerebral to give a sense of passion or its consequence. On this evening of Halloween a more festive ending would have certainly been more appropriate. But then Sherman did give the audience a smile before he packed his table and stalked out into the night.