Landscape (Western Hemisphere)

PAGE IN PROGRESS

For STILLS and VIDEO, click on “View Gallery” above.

VIDEO viewing suggestions: view on largest monitor available, in darkest room possible, with sound at highest comfortable volume.

For RELATED MATERIALS, click on links in left column.

Radio Interview by Andil Gosine, 2010

“Lorraine O’Grady’s Natures: A Conversation about ‘The Clearing’.” Thirty-minute radio program, narrated and hosted by Andil Gosine, with music by Nneka, produced by Omme-Salma Rahemtullah for NCRA, Canada. Conversation explores issues of sex, nature and love in O’Grady’s work.

National Campus and Community Radio Association

This half-hour show, extracted by Gosine from their longer video interview, made just before production began on Landscape (Western Hemisphre), focuses on O’Grady’s diptych “The Clearing” and explores issues of sex, nature and love in her work via a mix of the intellectual and the intimate.

****

RADIO TRANSCRIPT ( . . . )

(Opening music, “Uncomfortable Truth,” by Nneka”)

Gosine: ( . . . ) Another of O’Grady’s beautiful works will re-emerge this fall at Beyond/In Western New York, an international exhibit taking place at various galleries across Buffalo from September 24 to the end of 2010. The now 75 year-old artist’s featured contribution will be “The Clearing,” a large black and white photographic diptych that she completed in 1990. The left panel presented a naked couple—a black woman and a white man in passionate embrace, floating in the sky, hovering above the trees. On the ground below, a young boy and girl are pictured running after a ball as it rolls towards a pile of the adults’ discarded clothing. A handgun is flung amongst the assortment of clothes. In the right panel, set in the same landscape, the male figure is clothed in chain mail, and a skull replaces his face. He is leaning over the black woman’s naked, numb body and fondles her breast. Her face is turned away, her arms stiff at her sides, her eyes fixed on the sky above. ( . . . )

O’Grady: The Clearing has had a very interesting history, and. . . When I first showed it, at the INTAR show, which was the show that I made it for, that was a space that I controlled totally, this was MY show and this was all my work on the walls, and it occupied its place within that show which I have since come to call BodyGround, but it had many more elements than just BodyGround, so I didn’t really think of it as that controversial, you know, I just thought, it’s a wonderful piece and I like it, and it looks good on the wall, and it works well with these other pieces.

But the images created quite a stir. At some gallery spaces, curators often refused to show both panels of the piece.

I was invited to be in a show, a group show that was at, actually at David Zwirner, when he was still in Soho, and it was still an up-and-coming gallery, not the big blue-chip powerhouse that it is now, and a young woman from WAC was curating a show there. And it was about sex. . I can’t remember quite the name of the show now. . . . I didn’t realize it, but the hidden agenda of the show was to express in visual art this moment of sexual exuberance on the part particularly of white women. OK, this was the moment when white women were like really exploring and dynamically reinventing themselves sexually. . . . the curator asked me to give her a piece, and the only piece that I had that was remotely sexually explicit was this piece. So I gave her the diptych. But when I went to the show only the LEFT side of the diptych was present. Because this show was about, you know, sexuality as an uncomplicated, positive blessing. Not sexuality as a complicated life issue or even sexuality as an issue far more complicated for women of color than for white women, none of the modulations of sexuality were to be present in the show. And I said [laughs] what have you done, you’ve put my piece up and it’s not my piece. That was when I first began to realize that the two parts of The Clearing might be a bit much for a certain audience.

The Clearing proved to be “too much” for a whole lot of people.

The Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art (SECCA) was doing a show, not about sexuality, but about black women, and I offered The Clearing. SECCA is in Winston Salem. North Carolina, and the curator was a very nice guy but he was from the South, and when he saw the piece. . . it just threw him. And he said, “That’s not what sexuality is, or at least that’s not what it’s supposed to be.” But well, that’s what it is.

Even after O’Grady was invited to a take up a prestigious Fellowship to Harvard, she still encountered censorship of the work there, including discussion of it.

I put this piece in the show with three other artists who were Fellows, and I looked anxiously for the Radcliffe Quarterly’s review and discussion of the show. . . and everybody else’s piece was discussed, and everybody else’s piece was shown — except mine! Hmmm, well something’s wrong here, right. I got so upset and people sort of were surprised that I got so upset and so some. . . it went to the Harvard Magazine and an editor there said, Oh, what’s going on? and came over and talked to me, and I showed him and talked about the piece. He became very interested in it and wanted to write about it. And then when he proposed writing about it to his editor. . . he was the Managing Editor, I think, or the Assistant Editor, and he proposed writing about it to the Editor-in-Chief. . . and the Editor-in-Chief just said, “No.” And the only answer was, “We only have so much capital (goodwill), and I don’t intend to use any of it for this piece.” So it never got shown, I mean it was shown, but it never got discussed at Harvard, in any way.

O’Grady, it seemed, was airing thoughts that were not supposed to be spoken.

I don’t think most people want to think about the compromising, difficult parts of sexuality even among normally married couples, you know. But they certainly don’t want to hear about that difficulty in interracial relationships, or certainly they don’t want to have the historical nature of this relationship exposed en plein air.

The Clearing, O’Grady says, draws upon very common practices—but one that many people still feel very uncomfortable about acknowledging.

It’s very very very difficult for people to be living in the kind of intimacy that obtained on the Southern plantation without desire going in totally unexpected or unpredictable ways. I mean, how could you live day after day, year after year with a certain person and not eventually see him as a person, or not eventually at least see them as a sexual object. I’m not speaking, you know, about going down to relieve your tubes in the slave quarters, but I’m talking about just what the white woman was exposed to, which would be men. . . serving men, coachmen, men as whatever. . . Obviously there had to be some parallel relationship and in fact there was. But I didn’t realize this until I was teaching in Washington and there was a man who was teaching in the same high school [Eastern High School]. . . I taught there for about six months and I befriended a man, a wonderful man, [Colston] Stewart, and he came from Lynchburg, Virginia. One day he said something to me about the three different school systems in Virginia. . . this was the 60s (actually1964-65) and I said, What are you talking about? And he said, Yeah, there were three different school systems where. . . where I was growing up in Lynchburg ( . . . ) There was a school system for the whites. There was a school system for the blacks. And there was a school system for the free issues. And I said, “free issues? What are the free issues?” And he said, “They’re the children of the white women. Because,” he said, “the law in Virginia said that all children issuing. . . all children of white women issue free from the womb.” So if you had a child issuing free from the womb which was not white, then something had to be done with them. I don’t think anybody just murdered them, you know, they were free and they were being raised by white mothers, but they were segregated. And so there were whole towns in Virginia that became populated by free issues. . . . That was like a visible sign that was going on for decades, even centuries, that this desire not only existed but was acted on and ultimately couldn’t be policed totally.

After The Clearing’s debut presentation, O’Grady retitled the diptych in subsequent shows, in an effort to draw attention to the specific historical events she was drawing upon.

There is so much unacknowledged in the history of the colonization of the western hemisphere. The reason that I later subtitled The Clearing¬ as Cortez and La Malinche, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, as well as N.,you know, N period, meaning any Name and Me, is because actually the Western Hemisphere was founded in this relationship. La Malinche was an Aztec princess, but not really a very. . . a minor princess and somehow she learned Spanish, and as a result Cortez was able to conquer Mexico and the southern part of the peninsula with her help. Her name La Malinche kind of embodies the word traitor because she’s been considered the traitor of the Western Hemisphere, although now she is being recuperated by Mexican feminists as you might imagine. But this relationship, which in their case ultimately led to several children and so on, was there before the slaves came to the United States, before ENGLAND came to the United States, so it was foundational.

We think of this kind of relationship as unique but it was emblematic really of the relationships that were occurring throughout the South, for example, and were unacknowledged as part of what was actually making America “America.” So 500 years of history, yes, going all the way back to Cortez, but coming up through, 200 years later, Sally Hemings, and 200 years after that, Me, this is an absolute, continuous relationship that’s never discussed ( . . . ) and that’s why I made the piece. The piece was an attempt to start a discussion.

O’Grady especially hoped that “The Clearing” would trigger a discussion of the social aspects of sexual relationships.

Of course, the sexual relationship may always already be. . . (laughs) I hate that phrase, you know “always already”. . . imbricated in the social. ( . . . ) when we’re actually involved in the sexual act, we’re not thinking socially, we’re not feeling socially. We’re feeling totally individually. But then we’re called to account. Once the orgasm is finished, then we’re called to account and things, life, get much more complicated. ( . . . )

ArtFCity, 2016

Emily Colucci, “Black Is and Black Ain’t in Pace Gallery’s ‘Blackness in Abstraction’.” ARTFCITY.com. August 18, 2016.

Emily Colucci’s review of “Blackness in Abstraction” highlights O’Grady’s full-wall video “Landscape (Western Hemisphere)” as one of the exhibit’s most successful pieces both for its embrace of multiple meanings of blackness and for its abstract evocation of landscape sounds and textures.

****

“Black is and black ain’t.” Walking through Pace Gallery’s current exhibition Blackness in Abstraction, I began to think about that title line from Marlon Riggs’s final film—taken from the prologue of Ralph Ellison’s novel Invisible Man. Even more than the pervasive “Black is beautiful,” this curiously ambiguous phrase hints at the multitude of meanings, voices, and questions surrounding blackness in the exhibition.

Curated by Adrienne Edwards, the Walker Art Center’s visual arts curator at large, Blackness in Abstraction brings together a multigenerational group of artists who work with the color black. The show also gathers artists of varying races and ethnicities. This leads to a rich juxtaposition between abstract stalwarts like Sol LeWitt, Ad Reinhardt, Robert Rauschenberg, and Robert Irwin with black artists like Rashid Johnson, Wangechi Mutu, Terry Adkins and Carrie Mae Seems who are too often contextualized in relation to their racial identities. In contrast to shows like Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art, Blackness in Abstraction argues that identity can be a chapter but it isn’t the whole story. The show depicts what would happen if we looked beyond an artist’s own blackness to, instead, investigate their use of blackness.

Blackness in Abstraction presents a staggering variety of approaches to blackness with sixty multidisciplinary artworks—even more counting the numerous multiples. The show takes up the entirety of Pace Gallery, further expanding its exhibition space with several temporary walls. Fred Sandback’s multi-stranded minimalist yarn sculpture stretches tautly from floor to ceiling, Glenn Ligon’s photographic appropriation of James Baldwin texts fades to black when high on the wall, and Fred Wilson’s iconic, symbol-laden flag series hangs vertically in the corners. Adam Pendleton’s coded sculptural arrangement “Untitled (code poem Los Angeles)” even provides the gallery staff with some extra anxiety due to its precarious proximity to Pace’s entrance and clumsy visitors’ steps.

( . . . )

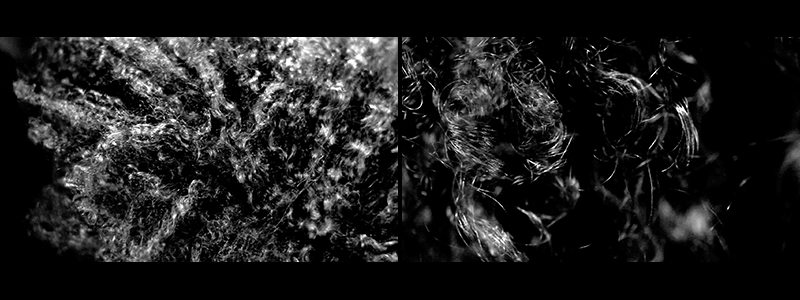

The multiplicity in McQueen’s photographs mirrors the complexity that runs through the most successful works in the show, which embrace the multiple meanings of blackness. Take, for example, Lorraine O’Grady’s video “Landscape (Western Hemisphere).” Entering a separate video gallery, the viewer hears sounds of chirping birds, insects and other surrounding environmental noise. The visuals immediately appear like a wave of flowing grass blown by the wind. Rather than a landscape, O’Grady’s video animates the landscape of the flowing curls in her natural hair.

Here Edwards’ curatorial strength comes to the fore. The video is clearly a powerful embrace of natural hair as a symbol of black femininity and beauty. But it can also be understood in the abstracted context of the rippled textures of Koji Enokura’s minimalistic painting on cotton that slides down a wall outside O’Grady’s video gallery. By combining these artworks, Edwards seems to be demanding more from viewers, art historians and curators. If we look beyond blackness as an either/or category in art—as either “identity” or “color”—what new understandings will we discover?

Adrienne Edwards, 2016

Adrienne Edwards, Blackness in Abstraction, “Lorraine O’Grady,” pp. 173-176. Pace, New York, 2016.

Adrienne Edwards’ essay on Landscape (Western Hemisphere), written for her “Blackness in Abstraction” exhibit curated for Pace Gallery, is an intellectually brilliant and poetically sensitive reading of the array of meanings residing in the video and the most complex statement on this piece to date.

****

LORRAINE O’GRADY has taken an archaeological, archival, and historicist approach to mine the past precisely by pursuing its and her own hauntings, transgressions, and becomings. This is especially evident in Landscape (Western Hemisphere), a 2010–11 eighteen-minute, single-channel video in which O’Grady transforms her hair into a moving abstract landscape. As each wavy strand sways, crinkles, and rustles to the wind, a faint collage of sound from the North American hemisphere’s rural and urban landscape is audible.

The term landscape has multiple nuanced and interrelated meanings: as a noun it can imply an art genre (as in landscape painting) or a topography (as in an expansive vista); and as a verb it connotes cultivation, disciplining, and contouring of the ground. In O’Grady’s video, all three definitions are interpolated. A foundational concern in her work is hybridity and the myriad ways in which it is a particularly distinguishing characteristic of the Western hemisphere. O’Grady’s hair testifies to the history of racial mixing and the historical, cultural, and social connotations associated with it. She addresses the implications of this history on social and economic status, the impermanence of racial boundaries, and the infelicity of racial authenticity. For O’Grady, hybridity:

is essential to understanding what is happening here. People’s reluctance to acknowledge it is part of the problem….The argument for embracing the “other” is more realistic than what is usually argued for, which is an idealistic and almost romantic maintenance of difference. But I don’t mean interracial sex literally. I’m really advocating for the kind of miscegenated thinking that’s needed to deal with what we’ve already created here.

Through her hair (indeed in all of her work), O’Grady puts forth a “metaphoric system” that is neither foundational, nor symbolic, nor definitive but rather resonates liminally in the fissure of hybridity and its productive capacity. In the interstices of O’Grady’s hair, we locate the remains of enslavement, the resilience and persistence of the specters—it is a testament of survival. We also find the pathways to transgressive resistance embedded in the heights, depths, and expanse of the waves of her hair. The waves are “the break” in which the hauntings of this past persist and the what-is-to-become mutually reside. This future becomes through transgressions, both a holding of the line and a crossing of it to some other plane by some other means.

Hyperallergic on O’Grady, 2015

Heather Kapplow, “A Walk Through the World of Lorraine O’Grady.” hyperallergic.com, December 31, 2015.

Heather Kapplow’s exceptional review of Where Margins Become Centers, O’Grady’s 2015 solo show, curated by James Voorhies at Harvard’s Carpenter Center for he Visual Arts (CCVA), replicates in ita writing both the organization of the exhibit and O’Grady’s creative process in developing a line of exposition through various art works over time.

****

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — When visiting an art exhibit, there’s a temptation to start at the entryway and work your way through it following the path established by the curator.

In the case of Lorraine O’Grady’s Where Margins Become Centers, at Harvard’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts (CCVA), resist the tyranny of convention and signage and enter via the back door.

Start with as little interpretation as possible. Sit in the dark on a bench for an entire 18 minutes, if you can spare them, and watch item #10 (of 10) on the exhibition checklist available in the catalogue downstairs and at the guard’s station at the main entrance to the gallery. In fact, open the publication, point to item #10 on the checklist, and ask the guard to direct you towards the back door to the piece to avoid being drawn in the intended way.

Lorraine O’Grady, “Landscape (Western Hemisphere)” (still, 2010/2011), single-channel video for projection, 18 min (image courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York) “Landscape (Western Hemisphere)” (2010/2011) consists of close-up footage of O’Grady’s hair and scalp paired with what seem to be a few varieties of ambient sound. It’s the climax of the show, but also the best way to prime yourself to absorb the rest of the show’s content as completely as possible.

If you move through things the way you’re supposed to, you’ll get caught up in the mathematics of identity, in the rights and wrongs of the art world, and in the aesthetics of documentation as art; “Landscape” will end up serving as a catharsis for all of the complexity and tension raised.

Avoid the catharsis.

Zoom in instead on the DNA of the matter. Meditate on all that gets coiled and released in the alwaysin-motion entanglements of our genes and history. Let the elusive, destabilizing scale of “Landscape”empty your mind. Let it hypnotize you, and then walk into the light of the main gallery, wherequestions begin to get asked more explicitly.

This is not a quiz, but consider these thoughts as you move through the inner gallery space: Can sexual intercourse encompass many contradictory experiences at the same time? What is the implication of a place becoming inextricably intertwined — grafted — with a body? When you lose your sister, can that loss be a conduit into a larger sense of what it means to be be “related” to people?

Use the exhibition guide and the following works to answer these questions:

In each of these pieces, which line the periphery of the gallery’s inner room, surrealism and juxtaposition are used to create spell-like parallels between the personal and the global, the past and the present — in the process problematizing distinctions between assumed binaries. For O’Grady, nothing is black and white. And yet everything is black and white.

At the center of the room, you’ll find two vitrines. They contain some of the copious documentation that O’Grady has created and archived relating to her most well-known work, a persona and performance intervention practice known as “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire.”

Decked out in a beauty-pageant style sash and crown, and a fabulous dress made of white gloves, O’Grady as Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (“Miss Black Middle Class”) appeared uninvited at a few choice art openings and other events in the early 1980s. These events were promoted as radically contemporary, but were in truth as racially segregated as they would have been 30 years prior.

Mlle Bourgeoise Noire’s most famous appearance was at the opening of the (then brand new) New Museum’s 1981 Persona show, where she appeared with an entourage and paparazzi and whipped herself while shouting poetry inciting black artists to take bigger risks. That’s the short version of the story. See the vitrines and the gorgeous custom (CCVA-made) table in the outer gallery for the full details (including tallied cost of materials) of this intervention, plus some frank correspondence between O’Grady, New Museum staff, and members of the press that followed.

By the time you exit the inner room, passing “Sisters I” — an unexplained pairing of a personal photograph with a chunk of ancient history — you should be thoroughly confused about what happened when and where. With your mind full of a stew that’s half rage and half wonder — wrought by the combination of more abstract, image-based work and the cold, hard archival material — you can move to the main gallery space and access the contextualization you were supposed to get on your way in.

Boston-bred O’Grady’s biography explains a few things about the four decades of work represented here, most usefully siting her experience as a biracial woman in a particular moment in time and space. Curator James Voorhies spells out the rest: “Her work challenges what is unwittingly agreed upon on a society-wide scale in a march towards dismantling accepted constructs.” Though the approach she takes to rattling the cages of these constructs (race, gender, class, the complex power structures of institutions) has shifted over time, her rallying cry against complacency is, as Voorhies observes, “no less topical today” than it was in the 1980s.

Finally, for some ambiguous closure, take a trip down the passageway that you followed to get into “Landscape (Western Hemisphere)” the back way. Here find several quasi-stately portraits of Michael Jackson and Charles Baudelaire, bookending an impossible sociocultural divide in a way that makes it seem a possible one. The placement of this dual-portrait series, The First and the Last of the Modernists (2010), makes it a great exit point.

Before you leave, turn to look at the windows across from the series and you’ll catch yourself among the reflections of these two men (and the gaps between them), overlaid on the surrounding institution. It seems fitting to be reminded of exactly where you stand — within a complex of nested, refracted, sometimes oblique reflections, and encased in an institution to boot — before you step back out into the larger world, where what O’Grady’s work challenges in the art world continues to need challenging as well.

Lorraine O’Grady: Where Margins Become Centers continues at the Carpenter Center for the

Visual Arts (Harvard University, 24 Quincy Street, Cambridge, MA) through January 10, 2016.

New York Times, 2012

Holland Cotter, “Lorraine O’Grady: ‘New Worlds.’” New York Times, Art in Review, p. C27, May 18, 2012.

Cotter’s impressionistic review captures the experience of watching the video, which seems always on the verge of providing resolution and catharsis but never does.

****

Video is alive and well represented at Alexander Gray Associates. A solo show by Coco Fusco at the gallery last month revolved around a meditative video about politics and the passing of time in contemporary Cuba. Lorraine O’Grady’s current solo show also has a video centerpiece, this one about the persona-as-political embodied in the artist herself.

In a career going back more than three decades, Ms. O’Grady has frequently called on her ethnic background — she was born to Jamaican parents in Boston — as a subject, and she does so again here, with deep ambivalence in two back-and-white photomontages. In one of them, a hybrid tree – half palm, half New England fir – protrudes like a freakish growth from the back of a prone dark-skinned body. In a diptych-format picture, an Edenic racially mixed coupling is matched with the figure of Death dancing.

The 18-minute-long video called “Landscape (Western Hemisphere),” made last year, is abstract by comparison. It’s a sustained image of what looks like a dense cluster of trees or bushes swept by a constant wind, set to a soundtrack that alternates urban noises and forest sounds. The restlessly moving foliage, which always seems about to reveal something beyond itself but never does, is a close-up of the artist’s gray hair blown by fans.

Hair as a marker of race and gender has done heavy duty in art over the last 20 years. Ms. O’Grady, now in her 70s, adds age to the symbolic mix, and keeps the turbulence constant. The result is the visual equivalent of a disturbing thought that won’t leave the mind alone.

Artforum.com, 2012

Lumi Tan, “Lorraine O’Grady.“ ALEXANDER GRAY ASSOCIATES. Critics’ Picks, artforum.com, May 9, 2012.

This Artforum “Critics’ Pick” review summarizes the ways in which both aspects of the New Worlds installation, the video and the photomontages, explore the same thematic material.

****

The centerpiece of Lorraine O’Grady’s exhibition “New Worlds” is Landscape (Western Hemisphere), 2011, a video that leads the viewer to initially believe its nineteen minutes of black-and-white footage depict something akin to a thicket upswept by the wind. An ambient sound track features birdcalls and cicada songs, but it hints at a more developed land through the distant rumble of train tracks. In actuality, what we see is O’Grady’s own hair in extreme close-up, shaking and swaying between two fans. The intentionally misleading title is an extension of O’Grady’s long-standing examination of cultural identity, specifically the colonized female body. This beautiful, straightforward video instantly conjures Western culture’s numerous presumptions about women of color: the exoticness of natural hair, a bodily connection to the land, and the expectations of performance from such bodies.

Two photomontages from O’Grady’s earlier “Body/Ground” series further this comparison; The Fir-Palm, 1991/2012, literally connects a hybrid tree to the small of a black woman’s back. More obliquely, the diptych Body/Ground (The Clearing: or Cortez and La Malinche. Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, N. and Me), 1991/2012, depicts on the left a white man and a black woman in a loving embrace floating among the clouds, and on the right a theatrical death, seemingly by the man’s own hand. O’Grady’s inclusion of herself in this lineup of history’s most notorious interracial couples demonstrates that even at present, she believes we remain beholden to the racist consequences of the New World.

Andil Gosine on New Worlds (L-WH), 2012

Andil Gosine, “Lorraine O’Grady’s NEW WORLDS.” Unpublished.

Though still unpublished at the time of the 2012 “New Worlds” show, this incisive essay by Gosine, a York University (Toronto) professor who’d written earlier on hybridity in O’Grady’s work, has since been published in the brochure for O’Grady’s solo show at Harvard University’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts (“When Margins Become Centers,” 2015), and, accompanied by Spanish translation, in the catalogue for her survey show at the Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo, Seville, Spain (“Lorraine O’Grady: Initial Reognition,” 2016). Gosine’s essay is the most complex and complete discussion of the interconnections between the video and the photomontages in the New Worlds installation to date..

****

Gently trembling quivers of hair provide a perfectly pitched and suitably gorgeous meditation on a conversation Lorraine O’Grady started twenty years ago. The artist’s conundrum then, as now, was herself and us. As she wrote on the wall of the 1991 New York exhibit in which the images first appeared: What should we do? What is there time for? What should we do with the mess of desires, identities and culture that mixing, both forced and free, has unleashed in the Americas since colonial encounter?

Her reply in that first solo show at the INTAR Hispanic American Arts Centre opened with two works from her series Body Is The Ground of My Experience (BodyGround): the delicate Fir-Palm, a black-and-white photomontage featuring a hybrid New England fir and Caribbean palm growing from a black woman’s torso, and The Clearing, a photomontage diptych showing conflicting scenes of interracial sex played out in black-and-white against the backdrop of a forest clearing. Twenty years later, for her 2012 solo show New Worlds at Alexander Gray Associates, the two are paired with her newest work, Landscape, Western Hemisphere, a mesmerizing eighteen-minute black and white wall-sized video projection that features those compelling soft and sharp movements of her hair.

The appropriately titled New Worlds is O’Grady’s tome on five hundred years of history. It offers further evidence of the artist’s prescience. A complex, subversive thinker, once overlooked, she has always made work that demands committed attention–no easy feat in any situation but especially difficult in an earlier, racially segregated art world that could not find place for her. The Fir-Palm establishes a context for one strand of a lifelong interrogation that has consumed her practice, revealing the tensions surrounding the artist’s identity and her production of body and desire as foundational for the development of the Western Hemisphere. Its botanic concoction embodies O’Grady’s heritage as the child of Caribbean immigrants who left Jamaica for Boston at the dawn of the twentieth century. The image is at once an assertive claim about her own hybridity and, through the clouds hovering in its background, an acknowledgment of its precarious condition. The Fir-Palm puts to picture Homi Bhabha’s “Third Space”; through O’Grady, Gayatri Spivak’s subaltern speaks.

If The Fir-Palm signposts hybridity, The Clearing is its visceral elaboration. In it, O’Grady’s arguments are teased out, beginning with the diptych’s subtitle: “or Cortez and La Malinche, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, N. and Me.” The imbrications of identity and culture with nature and sexuality are demonstrated in the scenes’ activities. In the left panel, a black woman and white man appear elevated in clouds, their expressions matching the ecstasy of their sexual engagement. Below, children are playing in the clearing, as a pile of the couple’s discarded clothes topped by a gun lies, carelessly, on the ground. There are no children in the image on the right. The black woman’s stiff corpse stretches out on the ground, while the white man, now wearing a skull as his head and robed in a chainmail vest, hangs over her.

( . . . ) The black-white union represented in the image is both dream and nightmare, neither a choice between them nor one ending with death, but a site of continuous tension. The sexual desires underpinning this engagement are fuelled through and through by colonial fantasies of “race.” Yet they also potentially facilitate the destabilization of the structuring essentialism that underpins colonial acts of violence. The personal experiences that drive O’Grady’s imagination and the production of The Clearing serve as testimony to the complicated experience of the colonial subject—to its simultaneous experience of violence with desire, of pain and punishment with dreaming and longing—and of the impossibility of resolution. The Clearing insists on a complicated reading of cultural hybridity, one that claims neither celebration or denunciation, but rather appreciates its simultaneous and inseparable brutalities and pleasures. The images comprising the diptych are not an ’either/or’ proposal but a ’both/and’ description of what is left in the aftermath of colonial encounter.

The Clearing is especially concerned with the interracial pairing it puts to picture, of the black woman and white man. In “Olympia’s Maid,” O’Grady theorized that the relationship between the white male and black female broke the “faith” between the white male and white female. It marked, she says, “the end of courtly love,” represented in The Clearing by the man’s chainmail shirt. The three relationships named in the sub-title situate this sexual pairing as central to the development of the Western Hemisphere. None are simply innocent representations of romantic love, nor are they simply condemnable in the terms of political morality.

Significantly, after the charged imagery of The Clearing, O’Grady returned to the poignant, more tender aesthetics of Fir-Palm for her first single-channel video Landscape, Western Hemisphere (2010). The idea of her hair as a landscape came about instantaneously. “I cannot tell you the thought process that arrived at my hair as a landscape,” she says. But once it did, her hair worked as an objective correlative to the trees in The Clearing. “I began to see that I identified with all parts of The Clearing,” she says. “I identified with the couple, I identified with the children, I felt that my hair was the result of the action that took place in The Clearing. This action,” she concluded, “which, for all that it may have happened elsewhere in the world, has to be identified determinatively with the Western hemisphere.” While interracial sex happened elsewhere, “only in the Western hemisphere was it this foundational, ultimately synthesizing action,” O’Grady says. “It couldn’t resonate in the same way elsewhere. It wouldn’t be foundational, it wouldn’t be symbolic, definitive. My hair,” she adds, “as a metaphoric system, could really only have existed here. It was symbolic of all the physiological, mental, and cultural hybridizations that were going on.” The title of the piece followed. “You know, I didn’t realize until I began to think about what to call the video that in The Clearing’s subtitle, Cortes and La Malinche were Latin America, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings were North America, and N. and Me, that was the Antilles. So I had unconsciously put all of it together, The Clearing was North, South and in-between.”

With Landscape, Western Hemisphere, O’Grady brings us into a necessary but permanently unstable resolution. “My attitude about hybridity,” she says, “is that it is essential to understanding what is happening here. People’s reluctance to acknowledge it is part of the problem… The argument for embracing the other is more realistic than what is usually argued for, which is an idealistic and almost romantic maintenance of difference. But I don’t mean interracial sex literally. I’m really advocating for the kind of miscegenated thinking that’s needed to deal with what we’ve already created here.”

What should we do? O’Grady’s is not an easy response. That it foregrounds the messy details and contradictions in negotiating colonial inheritances, is in fact part of her answer. The artist’s imperative to defy and disrupt hegemonic practices is essential to her work, but this is no anarchistic enterprise, oppositional for the sake of it. Rather, O’Grady’s work underlines the complex history of colonization, its contemporary persistence and the genuine difficulties for securing justice in the face of it. In her groundbreaking study of black female representation “Olympia’s Maid,” O’Grady wrote: “But, I tell myself, this cannot be the end. First we must acknowledge the complexity, and then we must surrender to it.”

Beyond/In Western New York, 2010

Alternating Currents: Beyond/In Western New York Biennial.

Carolyn Tennant, “Lorraine O’Grady.” Wall Text for O’Grady’s Buffalo Biennial installation at the Anderson Gallery, University at Buffalo, 2010

Tennant’s wall text connects two complementary pieces, O’Grady’s 1991 photomontage diptych The Clearing, and her later video Landscape (Western Hemisphere), 2010, via the concept of the bridge, referencing both the musical term and a frequently quoted phrase from O’Grady’s writing.

****

“Wherever I stand, I find I have to build a bridge to some other place.” Lorraine O’Grady

By presenting a video installation newly created for Beyond/In Western New York with a twenty-year-old photomontage diptych, Lorraine O’Grady creates a bridge for herself and for viewers, not simply to link two works but as a strategy that (re)engages with each work’s concepts. In music, the bridge serves as a section in the score that, in contrast with the chorus and the verse, prepares the listener for the approaching climax. Her new video Landscape (Western Hemisphere) responds to The Clearing (1991), a work that has not been recuperated by scholars and curators as have many of O’Grady’s other radical works, so as to encourage reconsideration of the earlier work. The new video emerged from a recent dialog with York University Associate Professor Andil Gosine, in which the artist spoke of her artistic intentions for The Clearing and described the work’s original reception, one of silencing and censure. The surrealistic photomontage depicts what filmmaker John Waters calls “the last taboo”: black and white sexual unions which O’Grady depicts as both born from desire and in service to power.

Landscape (Western Hemisphere) presents The Body as a landscape, harmoniously addressing many of the conceptual themes of the original diptych, later re-titled by the artist as The Clearing: or Cortez and La Malinche, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, N. and Me. When the two works are presented together, a new space is created—one where intertextuality and intersubjectivity can coexist. Just as the distinct panels of the diptych both function in contrast yet are seen together, the video and the diptych forge a “space between,” allowing the viewer greater access to the silenced work. O’Grady takes us to the bridge.