Cutting Out the New York Times

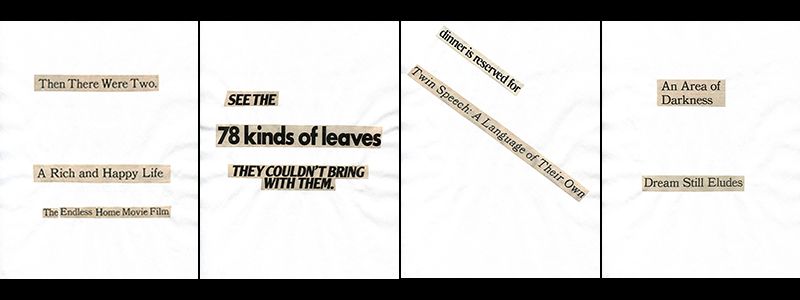

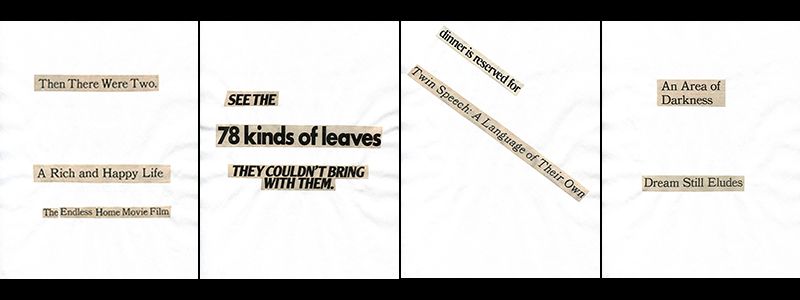

Cutting Out The New York Times is a series of 26 “cut-out” or “found” newspaper poems made by O’Grady on successive Sundays, from June 5 to November 20, 1977. They were first exhibited to the public at Daniel Reich Temp. at the Chelsea Hotel, in March 2006 at the urging of curator Nick Mauss. The slideshow here contains four of the poems in their entirety.

After graduating from college in the late 50s with a major in economics, O’Grady worked for five years as a young intelligence officer for the Departments of Labor and State, first on African and then on Latin American affairs. During that period, she was forced to read 10 national and international newspapers a day and — in the lead up to the Cuban Missile Crisis — three complete daily transcripts in Spanish of Cuban radio stations, as well as the endless overnight classified reports from agents in the field. It was a time, she’s written, when language “collapsed” for her, “melted into a gelatinous pool.” She soon quit her job as an intelligence analyst and began a roundabout journey into art.

1977 found her at SVA in New York, where her course in “Futurist, Dada and Surrealist Literature” attracted such students as John Sex, né John McLaughlin, Keith Haring, Kembra Pfahler, Luis Stand, and others. Cutting Out The New York Times was done in a moment of combined psychological and physical trauma (she’d just had a biopsy on her right breast which proved negative) and was accidentally begun while browsing the Sunday Times to make a thank-you collage for her doctor. She’d involuntarily wondered: what if, unlike Tzara and Breton’s random newspaper poems, she forced randomness back to meaning, rescued a personal sensibility from the public language that had swamped it, might she not get — rather than Plath and Sexton’s confessional poetry which made the private public — a “counter-confessional” poetry that could make the public private again? But with the rescue act accomplished, she forgot about the cutouts until Nick Mauss’s studio visit 30 years later.

This Will Have Been: My 1980’s (CONYT), 2012

“This Will Have Been: My 1980s.” Art Journal 71, no. 2 (Summer 2012): 6-17.

© Lorraine O’Grady, 2012

Based on her lecture in conjunction with the exhibit This Will Have Been: Art, Love and Politics in the 1980s, the article puts several early works in historical context and explains O’Grady’s reverse trajectory from “post-black” to “black.”

****

( . . . ) The newspaper poems of the young Dadas and Surrealists [during World War I] were a self-conscious surrender to the random in order to expose it, to bring the irrationality out from where it lay hidden and create a sur-realité, an “above” reality they could benefit from. My newspaper poems were almost the opposite of that. My last job with the government had been at the Department of State, in the Bureau of Intelligence Research (INR), the American Republics branch. It was during the Cuban crisis of the Kennedy years, and I had to read five to ten newspapers a day and plow through transcripts of three different Cuban radio stations. At a certain point in the day, you could watch language melt away. More than a dozen years later, in 1977, in my own little crisis, I started cutting headlines out of the Sunday New York Times. I would smoosh the cut scraps around on the floor until a poem appeared. My newspaper poems were more of a sous-realité, an “under” reality. They were an effort to construct out of that random public language a private self, to rescue a kind of rational madness from the irrational Western culture I felt inundated by, in order to keep sane.

In 1977, I was still post-black, and the poems were all about universal stuff, the meaning of life and art and all that. I did a poem a week for twenty-six weeks, and they averaged about ten pages each. But in 1979 I had an epiphanic experience at 80 Langton Street, an alternative space in San Francisco. I’d gone to see Eleanor Antin, whose 100 Boots I adored. I had no idea what to expect. As it turned out, she was doing a performance of Eleanora Antinova, her black ballerina character who had danced with Diaghilev in Paris after World War I. I liked the concept, it made me think of my mother Lena, of what might have happened had she emigrated from Jamaica to Paris as an eighteen-year-old instead of to Boston at exactly that time. But my mother was tall and willowy, the black ballerina type. And neither this short, plump white woman in blackface nor her out-of-kilter vision of the black character’s experience could compute for me. That was the moment I decided I had to speak for myself.

In 1980 I volunteered at Just Above Midtown, the black avant-garde gallery founded by Linda Goode Bryant that had lost its space on Fifty-seventh Street and now had to create a new space in Tribeca. ( . . . )

Re Cutting Out the New York Times, 1977 [2006]

“Re: Cutting Out the New York Times, 1977 [2006]” Unpublished artist statement.

© Lorraine O’Grady, 2006

At curator Nick Mauss’s request, O’Grady first exhibited five of the 26 cut-outs that she’d done on successive Sundays, from June 5 to November 20, 1977, in a group show nearly 30 years later — Between the Lines, in March 2006 at Daniel Reich Temporary (The Chelsea Hotel). She wrote this binder statement about her original work method and state of mind.

****

At the time, two things had happened simultaneously: I began to think that psychoanalysis might not be a bad idea; and I had to have a biopsy on my right breast. I took some books by André Breton to the hospital to help take my mind off it. Nadja and the Manifestos may have got mixed up with coming out of the general anaesthetic.

When the biopsy proved negative, I wanted to make a thank-you collage for my doctor. I thought it would feature the cult statue of Diana of Ephesus, the “many-breasted Artemis Ephesia.” But I needed some text. . . . As I was flipping through the Sunday Times, I saw a headline on the sports page about Julius Erving that said “The Doctor Is Operating Again.” It seemed too good to waste on the collage, so I made a poem instead. But since I’d been flirting with the doctor, the poem turned into an imaginary love letter for an imaginary affair.

Then I began to wonder, what if. . . instead of Breton’s random assemblages. . . I did cutouts and consciously shaped them? What would I discover about the culture and about myself? (In the place I was then, questions like “Who am I?” didn’t seem so academic). And, if I reversed the process of the confessional poets everyone still read at the time. . . like Plath and Sexton who’d made the unbearably private public. . . if I pushed the cutouts further, could I get a “counter-confessional” poetry that made the public private again?

To find myself in the language of the news didn’t strike me as odd. In my first job after college, I’d been an intelligence analyst, at the Department of Labor and then the Department of State. After five years of reading 10 newspapers a day in different languages, plus mountains of agents’ classified reports and unedited transcripts of Cuban radio, language had melted into a gelatinous pool. It had collapsed for me. That’s when I’d quit.

For six months in 1977, I made a poem a week from the Sunday Times. Cutting out the National Inquirer would not have interested me. This wasn’t about condescending to the culture, it was about taking back from it. It was just raw material. I think the process may have worked. When he read the cutouts, my ex-husband said it had been like leafing through the Times and coming across a photo of me accidentally. I never bought the Sunday Times again.

Alexander Gray Associates, 2015

Alexander Gray Associates, Lorraine O’Grady, May 28–June 27, 2015. Exhibition catalogue. Contains: Rivers, First Draft and Cutting Out the New York Times images, descriptions and analyses. Plus Lorraine O’Grady, “Rivers and Just Above Midtown,” pp 1-3. and “Production Credits, Rivers, First Draft,” p. 11. Published by Alexander Gray Associates. NY. ISBN: 978-0-9861794-2-6.

Fully illustrated, with analyses and descriptions of the 1977 “Cutting Out the New York Times” collaged poems and the 1982 “Rivers, First Draft” performance in Central Park (including production and music credits). Also contains bio and a new text by O’Grady celebrating premiere of RFD as a wall installation.

****

Cutting Out the New York Times was created over twenty-six consecutive Sundays during the summer of 1977, resulting in twenty-six text-based images assembled from headlines and advertising tag-lines. In a private and performative gesture, O’Grady explains, “I would smoosh the cut scraps around on the floor until a poem appeared.” At that time, O’Grady was teaching the course “Futurist, Dada and Surrealist Literature” at the School of Visual Arts in New York, while simultane- ously exploring alternative avenues of creative fulfillment and expression. Her interest lay in challenging the Dadaists’ and Surrealists’ embrace of the random and irrational as oppositional attitudes to rational Western society. O’Grady wel- comed the random in order to expose and force meaning back into it, making instead “an effort to construct out of that random public language a private-self, to rescue a kind of rational madness from the irrational Western culture I felt inun- dated by.”

The resulting work—digital color-prints of the original text—became a vital and transitional piece for O’Grady. She connects the piece to her personal history when she worked as an intelligence officer for the Departments of Labor and State in the years leading up to the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. Her job entailed reading ten newspapers a day, unedited transcripts of Cuban radio, and classified agent field reports. By the end, O’Grady states, “Language had melted into a gelatinous pool. It had collapsed for me.” Through Cutting Out The New York Times she investi- gated the potential of visual art through a linguistic mode. She viewed the creation of the poems as an aesthetic exercise, exploring a means of visual and performa- tive expression beyond the purely linguistic. Relating the poems to Concrete Poetry, O’Grady creates their visuality through the linear and syncopating place- ment of the cut-outs. The juxtapositions of size and style between the typefaces add to the collages’ visual rhythm. These poems present a highly personal narra- tive that touches on themes such as love, family, womanhood, hybridity, race, and self, subjects that would unfold in O’Grady’s subsequent performances and art- works.

Art Agenda, 2015

Alan Gilbert, “Lorraine O’Grady”, Alexander Gray Associates, NY, Art Agenda, June 30, 2015.

The editor of the College Art Association’s caa.reviews, through a close formal description of “Cutting Out the New York Times,” mimicked by that of the “Rivers, First Draft” wall installation, points to how their form provides an associative logic needed to make sense of the individuation process unfolding on the wall.

****

In the “Dada Manifesto on Feeble Love and Brittle Love” from 1920, Tristan Tzara famously provided instructions on how to write a Dada poem: get a news- paper and some scissors, snip out individual words and put them in a bag, shake it and then withdraw slivers of text, write down the words in the exact order in which they appear, and—voilà!—poem. Yet even more provocative than the method is Tzara’s claim that, “The poem will resemble you.” Similarly, although William Burroughs utilized the cut-up technique to undermine authorial intention and the way in which information serves as a means of control, the writings he produced in this manner continued to bear the impression of his obsessions: the police, queer sex, death.

Over the course of 26 Sundays in 1977, Lorraine O’Grady took scissors to the New York Times to create a series of text-based works recently on display at Alexander Gray Associates. If Tzara was convinced that his aleatory approach to writing a poem would nevertheless reflect the author, what does this involve for O’Grady, a crucial yet still somewhat overlooked artist of Caribbean descent who produced an important body of work in the late 1970s and early 1980s, including “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire” (1980–83), a set of performances/activist interventions for which she donned a dress made of white gloves and, most famously, crashed the opening of a New Museum show (“Persona,” 1981) in order to draw attention to the absence of nonwhite artists?

O’Grady’s exhibition at Alexander Gray was another iteration of the archival presentations of her work that have occurred at a number of different venues over the past decade or so. Cutting Out The New York Times (1977/2015) consists of 5—out of the original 26—series of newsprint-on-paper works that have been scanned, output on roughly letter-size adhesive paper, and affixed directly to the gallery’s walls with anywhere between 6 and 13 sheets per work, with 4 oriented horizontally and one installed vertically. O’Grady clipped phrases from the New York Times and scattered them on the floor, combining randomness with agency (. . . .)

Nick Mauss in Artforum (CONYT), 2009

Nick Mauss, “The Poem Will Resemble You: The Art of Lorraine O’Grady”. Artforum Magazine, vol. XLVII, no. 9, pp. 184-189, May 2009.

Mauss’s article for Artforum is, with Wilson’s INTAR catalogue essay, one of the most extended and authoritative pieces on O’Grady’s oeuvre to date. It was one-half of a two-article feature that also included O’Grady’s artist portfolio for The Black and White Show.

****

( . . . ) Even though [Mlle Bourgeoise Noire] appeared to have emerged out of nowhere, it has a long but decidedly not art-historical genesis.

O’Grady’s peripatetic biography and uncommonly varied occupations leading up to her artistic debut included studying economics and Spanish literature at Wellesley and a stint at the Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa, jobs at the US Bureau of Labor Statistics and the State Department in Washington, an attempt at writing a novel, a successful career as a rock critic for the Village Voice and Rolling Stone, and extended teaching at New York’s School of Visual Arts on subjects ranging from Dada to Catullus. But it was at the end of a hospital stay in 1977 that O’Grady began shifting from conventional aspirations as a writer to constructing poems that make spacious, looping fields of words out of phrases clipped from the Sunday New York Times. Headlines and ad copy glued in spare, dynamic arrangements on blank sheets of paper look less like ransom notes than like Mallarmé’s experimental typography. “At the time, two things had happened simultaneously,” she recalls. “I began to think that psychoanalysis might not be a bad idea; and I had to have a biopsy on my right breast. I took some books by André Breton to the hospital to help take my mind off it. Nadja and the Manifestos may have got mixed up with coming out of the general anesthetic.”

Transforming Faces

THE WOMAN AS ARTIST

COSMETIC LIB FOR MEN

Years Ago it Was a LANDSCAPE OF THE BODY

An Escorted Tour

Around Chicago

Birthplace of the Skyscraper

“The poem will resemble you,” Tristan Tzara warns in his step-by-step instructions for creating a Dada poem. But unlike similar experiments in making the familiar strange, O’Grady’s poems make the familiar deeply personal, refusing the generation of accidental meaning and the thrill of nonsense that are the prerogative and legacy of the white male avant-garde. These poems know that to mean something is difficult enough. Though the disunity of the poems’ parts is camouflaged by the congenial tone of the newspaper from which they are cut, the cloak of language quivers against what it is being made to say. Turning the technique in on itself, O’Grady finds herself everywhere and re-collects herself in a process meant to generate randomness. Predating by three years Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, these poems crystallize an aesthetic that demands critique be both concussive and elegant.

The modern artist,

finding himself with

no shared

foundation, has

begun to build on

Reckless Storytelling

STAR WORDS

and

The Deluxe Almost-Everything-Included

WORK OF ART

This could be The Permanent Rebellion

that lasts a lifetime.

Calling a Halt

To the Universe

BECAUSE LIFE DOESN’T WAIT

THE SAVAGE IS LOOSE

where we are

“Calling a Halt To the Universe”—this is what O’Grady did as Mlle Bourgeoise Noire. . . .

The New York Times, 2006

Holland Cotter, “Between the Lines”. Art in Review, New York Times, March 24, 2006.

A of three simultaneous shows presented by the Daniel Reich Gallery, NYC, which singles out O’Grady for special mention in the third.

Hernan Bas: Dandies, Pansies & Prudes Daniel Reich Gallery, Chelsea 537A West 23rd Street Through April 8

Christian Holstad: Leather Beach Daniel Reich Temporary Space 200 East 43rd Street, Manhattan Through May 1

‘Between the Lines’ Daniel Reich Gallery Temporary Space at the Chelsea Hotel 222 West 23rd Street, Room 103 (second floor), Chelsea Through April 8

Daniel Reich’s gallery was like no other when it opened in his Chelsea studio apartment in 2003. The work he showed there — small, finely wrought, but scrappy and pack-ratty — seemed ideally suited to the space. For that reason, when he moved to a standard white box on West 23rd Street, nothing quite seemed to jell for a while. But now the growing pains are over, and Mr. Reich has landed on his feet with one of the most interesting programs of any gallery in town.

More accurately, he has landed on several feet, as he is operating out of three spaces, two of them temporary. In his permanent gallery on West 23rd Street, he has new paintings by the Miami-based Hernan Bas, pictures of willowy young men filtered through screens of swipey, streaky acrylic and gouache. Some people find Mr. Bas’s work slight and derivative; I do not. To me, his paintings are elements in a larger, continuous conceptual-performance piece about being gay in 21st-century America. He understands that “gay” is a larger and more interesting category than “artist,” and one still embattled and historically underexplored. I value whatever he brings to that history.

I feel exactly the same about another Reich artist, Christian Holstad. His current show, “Leather Beach,” installed in a former delicatessen on the corner of East 43rd Street and Third Avenue, is a zanily brilliant meditation on the urban leather culture that achieved critical mass in the pre-AIDS 1970’s before fading from view. To some observers, its diminishment indicates a mainstreaming of gay self-perception. But Mr. Holstad complicates and resists such a possibility with an array of hand-stitched faux-leather gear that incorporates pompons, chains, human hair and glitter, and bonds Tim of Finland to the Cockettes. By diving deep into queer history, Mr. Holstad helps initiate a new history. In his art, “gay” gets its groove back.

Finally, at Mr. Reich’s third space, a suite at the Chelsea Hotel, the artist Nick Mauss has assembled an excellent group show. It includes Ken Okiishi’s shrewd homages to David Wojnarowicz and a beautiful drawing by the too-little-seen Daniel McDonald. There is a bright newcomer in Kianja Strobert, and two European artists — Tariq Alvi and Paulina Olowska — ripe for New York solos. The plum presence, though, is Lorraine O’Grady, one of the most interesting American conceptual artists around. And it makes total sense that she would fall within the unpredictably spinning Reich compass.