Cutting Out CONYT

In 1977, I was 43. After teaching Futurist, Dada, and Surrealist Literature for several semesters, I experienced a familiar female health crisis. There was a lump in my breast that required a biopsy. In my hospital bag, I packed two books by Andre Breton, the leading Surrealist, for distraction: his novel “Nadja” and “Surrealist Manifestos” with automatic writings made by taking dictation from the unconscious and newspaper poems created by cutting and throwing random headlines.

Perhaps it was the fear that had concentrated my mind. But when the biopsy turned out negative and I was home writing a thank you note to my doctor, I suddenly understood what had been bothering me about the Dadas and Surrealists, and what I would have to do.

In the 1910’s, draft dodgers from Northern and Central Europe fled to Switzerland to avoid the craziness of World War I—no one understood why it was being fought and yet it killed more people proportionally than World War II. Young artists gathered in the clubs of Zurich and Basel to protest. Feeling themselves victims of their 19th Century educations and their 19th Century parents who had sworn to them that Europe’s civilization was based on rationalism, they proposed instead a sur-reality (an above-reality) that, by surrendering to the random, would show the true irrationality of European culture.

As a black person born and living in North America at a time when we still learned about ourselves from white media, I felt honesty required that I would have to take the cuttings for my newspaper poems from The New York Times, a paper I had been reading most of my life. But as a black woman, I could not afford to submit to the random, I would have to control the random. Unlike the young Dadas and Surrealists, I had been aware of the basic irrationality of Euro-American culture from my earliest childhood. To make the public language private as a way of discovering what I truly thought and felt, I would have to cut consciously and poetically. My goal was to propose a sous-reality (an under-reality) that would be flexible enough to contain and increase comprehension of their world and mine.

Ambitious as I was, though, it wasn’t enough to make the public private. I wanted to achieve strong poems, to create a counter-confessional poetry that would confess from the outside in, paralleling the poetry that confessed from the inside out as in the work of Ann Sexton and Sylvia Plath and other writers of the time.

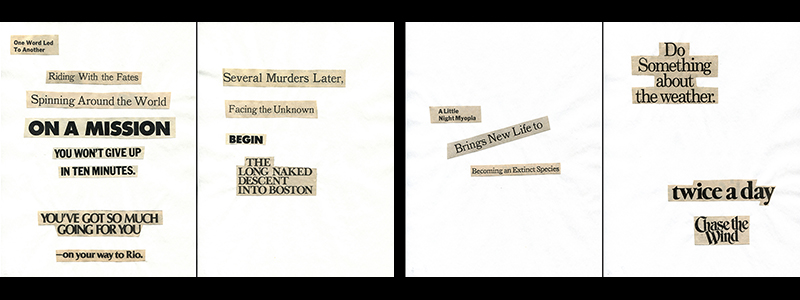

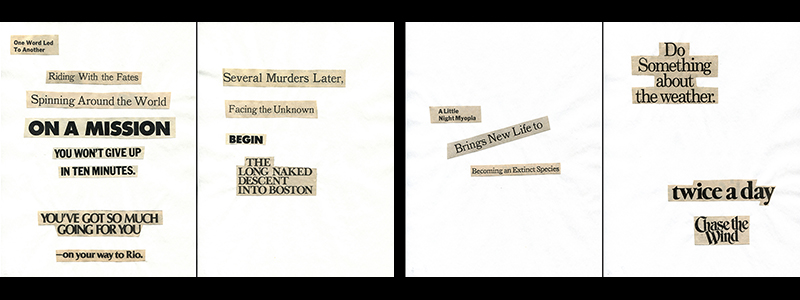

Cutting Out the New York Times (CONYT), 1977, was a group of 26 newspaper poems made in the last 26 weeks of 1977, averaging 10 panels/pages each. I’d succeeded in making public language private and had produced an accurate representation of who I mostly was during those weeks—a woman in early middle age, fearful of the loss of something she’d always counted on, the power of sexual attraction.

One evening after swimming the usual 47-minute mile in Manhattan Plaza’s olympic pool, I was walking my old Raleigh 3-speed toward the highway to begin the 15-mile ride up to 125th Street, then down to the Battery and back, when a nice-looking middle-aged black worker sitting on a stoop called out to me: “Oh, Mama, you’ve got a whole lot of life left in you yet! A whole lot!” I knew he’d meant it appreciatively, but for me it felt like the end of the world. I turned my bike away from the highway, rode home and went straight to bed.

Still, it wasn’t enough just to have made the public language private. I’d also wanted to make strong counter-confessional poetry. But when I read the poems I knew that I had failed. They were too distended and too trapped in elaborate composition rules for cutting and arrangement. I put them in an archival box and forgot about them for 30 years.

When I first put up my website in 2008, I didn’t include CONYT. I added it later, and then only 5 of the 26 poems that I thought worked “well enough,” and let it go at that.

It wasn’t until 2017, CONYT’s 40th anniversary year, when by fortuitous coincidence the German printer Rene Schmitt said he’d like to do a project with me, that I thought, “If not now, when?” After all, I had 40 years of life and career experience as a critically recognized visual artist to bring to the task. ( … )

For ARTFORUM INTERVIEW

November 19, 2018 • Lorraine O’Grady on creating a counter-confessional poetry, see:

http://www.artforum.com/interviews/lorraine-o-8217-grady-on-creating-a-counter-confessional-poetry-77735