Body Is the Ground of My Experience

BodyGround, shorthand for Body Is the Ground of My Experience, refers to the photomontages produced by O’Grady for her first one-person exhibit, at INTAR Gallery, NYC, Jan 21–Feb 22, 1991. The phrase doesn’t name a series — the works were unrelated — but rather the concern shaping O’Grady’s writing, thinking, and art-making at the time. The photomontages reprised several ideas from Rivers, First Draft in still form. Her move from performance to the wall had financial, personal, and theoretical motives. The work was growing both more direct and more complex and needed repeated viewings.

During her absence from the art world, O’Grady had become concerned about postmodernism’s over-simplifications which she felt re-located subjectivity away from the body to history in a way conveniently serving those in power. For while the body undoubtedly received history’s effects and was shaped by them, it was also, in an excess, the location of resistance. To make the point, her new photomontages — made the old-fashioned way just before Photoshop — eschewed both her earlier work’s layered beauty and postmodern photography’s dry formalism. Instead, they employed a psychological literalness reminiscent of Surrealism. In the Gaze and Dream quadriptychs, the bodies schematically enact both subjectivity’s stunting by history and latent resistance to it. And a group of three images, including The Strange Taxi and The Fir-Palm, employ a black body as a literal ground on which history acts but is unexpectedly modified.

O’Grady had not anticipated the intensely negative response, especially from white male viewers, to The Clearing, a diptych showing black and white bodies in what director John Waters calls “the last taboo.” One white male Harvard professor told her it was difficult to look at because it showed “how erotic domination is.” During this period, O’Grady experienced more success, especially with female audiences, via writings such as “Olympia’s Maid” and the articles in Artforum.

BodyGround Image Descriptions, 2010

“Body Is the Ground of My Experience” Image Descriptions. Unpublished artist statement, 2010.

© Lorraine O’Grady, 2010

Written to answer FAQs about the works without prescribing viewers’ responses. The photomontages were not based in Surrealist or Dada randomness. To make arguments and not just images or dreams, rational sources were twisted so unfamiliar subjective material of the “other” might enter.

****

“Body Is the Ground of My Experience”

black-and-white photomontages, varied sizes, 1991

DIPTYCHS:

THE CLEARING: OR, CORTEZ AND LA MALINCHE, THOMAS JEFFERSON AND SALLY HEMINGS, N. AND ME.

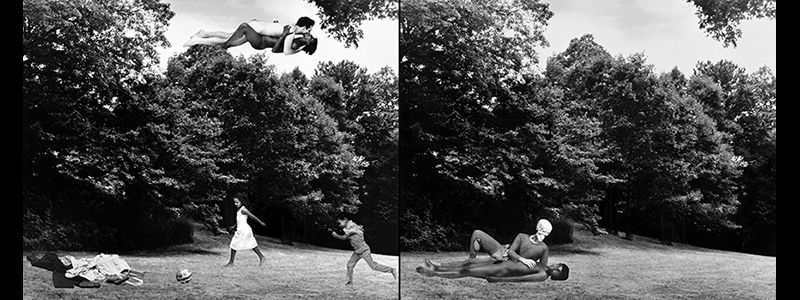

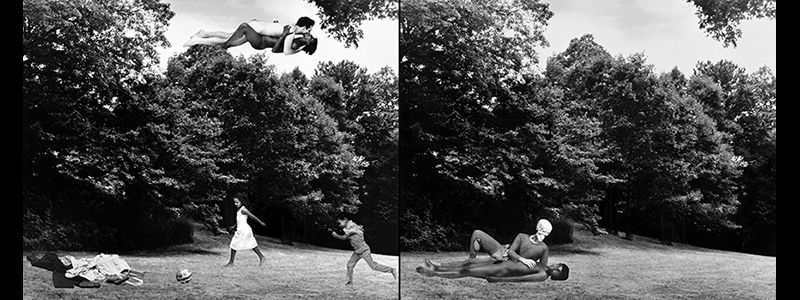

The diptych presents the both/and extremes of ecstasy and exploitation of this troubled and still under-theorized historic relationship. In the left panel, a naked couple deliriously “floats on air” above the trees while in the clearing below two mixed-race children play near a forgotten pile of clothing where a gun rests, threatening the scene. In the right panel, the skull-headed male figure proprietarily grasps the passive female’s breast. He wears tattered chain mail as if to argue that this foundational relationship of the Western Hemisphere, and its attendant duplicities, were the death of medieval “courtly love.”

DRACULA AND THE ARTIST. Left Panel: DREAMING DRACULA.

Right Panel: DRACULA VANQUISHED BY ART.

The image in the left panel, “Dreaming Dracula,” shows a black woman with broken, unkempt hair, dressed in a loose white shift. Her attention is focused on the flight of broken-toothed combs descending toward her on a shaft of light. To the right, in the panel “Dracula Vanquished by Art,” the same woman sits at a small wood table writing on a pad. Though there is a desk lamp, the illumination seems to come from the table itself, and her hair, still broken but now more “intentional,” is haloed by its light. The flight of combs lies spent in a corner of the room.

COLLAPSED DIPTYCHS:

THE FIR-PALM

The foliage of a New England fir tree grows from a tropical palm trunk that in turn springs from an African woman’s navel. Before becoming a photomontage, this botanical conceit for the artist’s cultural background was originally a prop in the 1982 performance Rivers, First Draft.

THE STRANGE TAXI: FROM AFRICA TO JAMAICA TO BOSTON IN 200 YEARS

The artist’s mother Lena (second from left) and her maternal and paternal aunts have been montaged from photos dating from 1915-25, the great period of West Indian migration to the United States. They are sprouting from a New England mansion of the type they had to work in as ladies’ maids when they first arrived. The mansion-on-wheels rolls down the African woman’s back.

LILITH SENDS OUT THE DESTROYERS

Destroyer-class warships spray out from the African woman’s

crotch, but some return to wound the woman herself. Lilith, the African model for BodyGround, coincidentally shared the name of Adam’s first wife who, having been created at the same time and from the same clay as Adam, felt herself his equal. Lilith refused to submit to Adam, instead left Eden and was replaced by Eve. She then gave birth to 100 babies a day by countless lovers of her choice, causing trouble in the world.

GAZE and DREAM

Models from the arts were elements of an idealized portrait of reality and potential.

In GAZE they were asked, for the outer figure, to express a combination of anger and contempt—the kind of look they might have if they thought someone were stupid, but couldn’t say so; and for the inner figure, quiet pleasure, as if a secret thought had made them smile to themselves.

Those in DREAM were asked to pretend, for the outer, that they were having a light and amusing dream; and for the inner, to imagine themselves submerged in deep spiritual trance.

GAZE info: Gaze 1 was a sculptor and performance artist; Gaze 2, a jazz band leader; Gaze 3, a choreographer; and Gaze 4, a classical music composer.

DREAM info: Dream 1 was an art historian; Dream 2, a painter and installation artist; Dream 3, a costume conservator; and Dream 4, a sculptor.

Radio Interview by Andil Gosine, 2010

“Lorraine O’Grady’s Natures: A Conversation about ‘The Clearing’.” Thirty-minute radio program, narrated and hosted by Andil Gosine, with music by Nneka, produced by Omme-Salma Rahemtullah for NCRA, Canada. Conversation explores issues of sex, nature and love in O’Grady’s work.

National Campus and Community Radio Association

This half-hour show, extracted by Gosine from their longer video interview, made just before production began on Landscape (Western Hemisphre), focuses on O’Grady’s diptych “The Clearing” and explores issues of sex, nature and love in her work via a mix of the intellectual and the intimate.

****

RADIO TRANSCRIPT ( . . . )

(Opening music, “Uncomfortable Truth,” by Nneka”)

Gosine: ( . . . ) Another of O’Grady’s beautiful works will re-emerge this fall at Beyond/In Western New York, an international exhibit taking place at various galleries across Buffalo from September 24 to the end of 2010. The now 75 year-old artist’s featured contribution will be “The Clearing,” a large black and white photographic diptych that she completed in 1990. The left panel presented a naked couple—a black woman and a white man in passionate embrace, floating in the sky, hovering above the trees. On the ground below, a young boy and girl are pictured running after a ball as it rolls towards a pile of the adults’ discarded clothing. A handgun is flung amongst the assortment of clothes. In the right panel, set in the same landscape, the male figure is clothed in chain mail, and a skull replaces his face. He is leaning over the black woman’s naked, numb body and fondles her breast. Her face is turned away, her arms stiff at her sides, her eyes fixed on the sky above. ( . . . )

O’Grady: The Clearing has had a very interesting history, and. . . When I first showed it, at the INTAR show, which was the show that I made it for, that was a space that I controlled totally, this was MY show and this was all my work on the walls, and it occupied its place within that show which I have since come to call BodyGround, but it had many more elements than just BodyGround, so I didn’t really think of it as that controversial, you know, I just thought, it’s a wonderful piece and I like it, and it looks good on the wall, and it works well with these other pieces.

But the images created quite a stir. At some gallery spaces, curators often refused to show both panels of the piece.

I was invited to be in a show, a group show that was at, actually at David Zwirner, when he was still in Soho, and it was still an up-and-coming gallery, not the big blue-chip powerhouse that it is now, and a young woman from WAC was curating a show there. And it was about sex. . I can’t remember quite the name of the show now. . . . I didn’t realize it, but the hidden agenda of the show was to express in visual art this moment of sexual exuberance on the part particularly of white women. OK, this was the moment when white women were like really exploring and dynamically reinventing themselves sexually. . . . the curator asked me to give her a piece, and the only piece that I had that was remotely sexually explicit was this piece. So I gave her the diptych. But when I went to the show only the LEFT side of the diptych was present. Because this show was about, you know, sexuality as an uncomplicated, positive blessing. Not sexuality as a complicated life issue or even sexuality as an issue far more complicated for women of color than for white women, none of the modulations of sexuality were to be present in the show. And I said [laughs] what have you done, you’ve put my piece up and it’s not my piece. That was when I first began to realize that the two parts of The Clearing might be a bit much for a certain audience.

The Clearing proved to be “too much” for a whole lot of people.

The Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art (SECCA) was doing a show, not about sexuality, but about black women, and I offered The Clearing. SECCA is in Winston Salem. North Carolina, and the curator was a very nice guy but he was from the South, and when he saw the piece. . . it just threw him. And he said, “That’s not what sexuality is, or at least that’s not what it’s supposed to be.” But well, that’s what it is.

Even after O’Grady was invited to a take up a prestigious Fellowship to Harvard, she still encountered censorship of the work there, including discussion of it.

I put this piece in the show with three other artists who were Fellows, and I looked anxiously for the Radcliffe Quarterly’s review and discussion of the show. . . and everybody else’s piece was discussed, and everybody else’s piece was shown — except mine! Hmmm, well something’s wrong here, right. I got so upset and people sort of were surprised that I got so upset and so some. . . it went to the Harvard Magazine and an editor there said, Oh, what’s going on? and came over and talked to me, and I showed him and talked about the piece. He became very interested in it and wanted to write about it. And then when he proposed writing about it to his editor. . . he was the Managing Editor, I think, or the Assistant Editor, and he proposed writing about it to the Editor-in-Chief. . . and the Editor-in-Chief just said, “No.” And the only answer was, “We only have so much capital (goodwill), and I don’t intend to use any of it for this piece.” So it never got shown, I mean it was shown, but it never got discussed at Harvard, in any way.

O’Grady, it seemed, was airing thoughts that were not supposed to be spoken.

I don’t think most people want to think about the compromising, difficult parts of sexuality even among normally married couples, you know. But they certainly don’t want to hear about that difficulty in interracial relationships, or certainly they don’t want to have the historical nature of this relationship exposed en plein air.

The Clearing, O’Grady says, draws upon very common practices—but one that many people still feel very uncomfortable about acknowledging.

It’s very very very difficult for people to be living in the kind of intimacy that obtained on the Southern plantation without desire going in totally unexpected or unpredictable ways. I mean, how could you live day after day, year after year with a certain person and not eventually see him as a person, or not eventually at least see them as a sexual object. I’m not speaking, you know, about going down to relieve your tubes in the slave quarters, but I’m talking about just what the white woman was exposed to, which would be men. . . serving men, coachmen, men as whatever. . . Obviously there had to be some parallel relationship and in fact there was. But I didn’t realize this until I was teaching in Washington and there was a man who was teaching in the same high school [Eastern High School]. . . I taught there for about six months and I befriended a man, a wonderful man, [Colston] Stewart, and he came from Lynchburg, Virginia. One day he said something to me about the three different school systems in Virginia. . . this was the 60s (actually1964-65) and I said, What are you talking about? And he said, Yeah, there were three different school systems where. . . where I was growing up in Lynchburg ( . . . ) There was a school system for the whites. There was a school system for the blacks. And there was a school system for the free issues. And I said, “free issues? What are the free issues?” And he said, “They’re the children of the white women. Because,” he said, “the law in Virginia said that all children issuing. . . all children of white women issue free from the womb.” So if you had a child issuing free from the womb which was not white, then something had to be done with them. I don’t think anybody just murdered them, you know, they were free and they were being raised by white mothers, but they were segregated. And so there were whole towns in Virginia that became populated by free issues. . . . That was like a visible sign that was going on for decades, even centuries, that this desire not only existed but was acted on and ultimately couldn’t be policed totally.

After The Clearing’s debut presentation, O’Grady retitled the diptych in subsequent shows, in an effort to draw attention to the specific historical events she was drawing upon.

There is so much unacknowledged in the history of the colonization of the western hemisphere. The reason that I later subtitled The Clearing¬ as Cortez and La Malinche, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, as well as N., you know, N period, meaning any Name, and Me, is because actually the Western Hemisphere was founded in this relationship. La Malinche was an Aztec princess, but not really a very. . . a minor princess and somehow she learned Spanish, and as a result Cortez was able to conquer Mexico and the southern part of the peninsula with her help. Her name La Malinche kind of embodies the word traitor because she’s been considered the traitor of the Western Hemisphere, although now she is being recuperated by Mexican feminists as you might imagine. But this relationship, which in their case ultimately led to several children and so on, was there before the slaves came to the United States, before ENGLAND came to the United States, so it was foundational.

We think of this kind of relationship as unique but it was emblematic really of the relationships that were occurring throughout the South, for example, and were unacknowledged as part of what was actually making America “America.” So 500 years of history, yes, going all the way back to Cortez, but coming up through, 200 years later, Sally Hemings, and 200 years after that, Me, this is an absolute, continuous relationship that’s never discussed ( . . . ) and that’s why I made the piece. The piece was an attempt to start a discussion.

O’Grady especially hoped that “The Clearing” would trigger a discussion of the social aspects of sexual relationships.

Of course, the sexual relationship may always already be. . . (laughs) I hate that phrase, you know “always already”. . . imbricated in the social. ( . . . ) when we’re actually involved in the sexual act, we’re not thinking socially, we’re not feeling socially. We’re feeling totally individually. But then we’re called to account. Once the orgasm is finished, then we’re called to account and things, life, get much more complicated. ( . . . )

Interview by Laura Cottingham (BG), 1995

“Lorraine O’Grady: Artist and Art Critic.” Interview by Laura Cottingham, in Artist and Influence 1996, vol. XV, pp. 205-218. Nov 5, 1995.

© Hatch-Billops Collection, Inc. 1996

In-depth interview conducted for the excellent Artist and Influence series produced by Camille Billops and James Hatch for their archive of African American visual and theatre arts.

****

This is my good friend Laura Cottingham. We’ve been having conversations like this for some time now.

( . . . )

For me your recent work, like the “Miscegenated Family Album” as well as “The Clearing,” deals directly with heterosexual relationships, which means black and white, especially between the black woman and the white man. Could you talk about that and how that subject and content comes to you and how you feel it’s perceived?

I don’t know if it’s been because of my own personal experience, because of the times in which I grew up, always finding myself the only black woman surrounded by a sea of white people and thus almost of necessity dating white men, but I have always understood racism not in economic terms, but in sexual terms. I don’t think racism could have the kind of intensity it has if it were simply, as the Marxists say, “an economic problem.” It is certainly an economic problem, precisely because it is a psychological problem, but the psychological precedes and makes the economic exploitation possible. Interracial sex, and the fear surrounding it, seems to me to be at the nexus of the country’s social forces. Within the various permutations, of course, the black male/white female is the most symbolically potent. It represents the fear of the loss of power; it is a negative symbol, if you will, embodying the very structure of white fear. The white male/black female (or the female of color all over the world) on the other hand, is a positive symbol, an expression of what the power is FOR, rather than a reaction to the potential loss of power. And since it is the expression of power, I feel that is nearer the crux of the situation. If you can examine that, bring it to light and make it objectively viewable, then you can perhaps create an interesting discussion. I’m not sure that you can change the world, but at some level I believe in the psychoanalytic theory which states that problems can be made manageable through the handling of images and words. The more familiar an image becomes, the more it can be discussed, and perhaps then the more it can be psychologically manipulated in a social context.

You have said before that you consider that particular context to be the most controversial in the images that you have produced so far. Do you still feel that?

I read an interview in Artforum with John Waters, who said, “Black and white is the last taboo, although nobody talks about it.” I think that in fact it is. And although the white male/black female is more underground as a taboo than the black male/white female, its very hidden quality makes it the most difficult to come to grips with. All I know is that I have been having some real difficulty in getting people to focus on the imagery. A few months ago when I showed “The Clearing” at the Bunting Institute at Harvard, it made people uncomfortable. One white male professor of history confessed that he found it very difficult to look at. When I asked him why, he said because it talked about how erotic domination is.

For those not familiar with your work, could you please give a description of the content of that work?

“The Clearing” is a diptych that I did for my INTAR show in 1991. On the left side, a white male and a black female nude are making love in the trees. The couple is very obviously happy. Below them on the ground you see a pile of discarded clothing and two mixed-race children running after a ball. On the pile of clothing is a gun silently threatening the scene. On the right side it’s the same background, the same clearing of trees, only now the black woman is lying on the ground looking off into the distance with a very bored expression; the white male is now dressed in tattered chain mail, and his head has been replaced by a skull. His attitude is clearly proprietary, as he absentmindedly grasps her breast. I put him in chain mail because I felt that this relationship, and the duplicities it implied for white women, was the death of courtly love.

Something that seemed to bother people was that I changed the title in order to make it more explicit. In 1991 it was called simply “The Clearing,” but now it is “The Clearing, or Cortez and La Malinche, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, N. and Me.” So the piece has been historicized in that way. And it isn’t a “before/after” piece; it’s a “both/and” piece. This couple is on the wall in the simultaneous extremes of ecstasy and exploitation. I think the piece is saying something interesting and complex about relationships. Not just about this particular relationship, but about all sexual relationships.

What do I think about the subject matter? The subject matter of miscegenation and interracial sex? I certainly don’t think it is an evil in itself or at all. But to the degree it is still a symbol of the “other’s” exploitation culturally, sexually, and in every way, I think it’s what we’ve got to come to grips with worldwide before we can move on. Every time I think that the subject matter is old-fashioned, I get brought up short by how contemporary it is ( . . . )

Olympia’s Maid, 1992, 1994

“Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity.”

Opening section published as illustrated essay in Afterimage, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 14-15, Summer 1992.

Final “Postscript” section added and full essay published in Frueh, Langer, Raven, New Feminist Criticism: Art/Identity/Action, pp. 152-170, HarperCollins, 1994.

© Lorraine O’Grady, 1992, 1994

This first-ever article of cultural criticism on the black female body was to prove germinal and continues to be widely referenced in scholarly and other works. It has been frequently anthologized, most recently in Amelia Jones, ed., The Feminism and Visual Cultural Reader, pp 208-220. Routledge, 2010.

****

The female body in the West is not a unitary sign. Rather, like a coin, it has an obverse and a reverse: on the one side, it is white; on the other, non-white or, prototypically, black. The two bodies cannot be separated, nor can one body be understood in isolation from the other in the West’s metaphoric construction of “woman.” White is what woman is; not-white (and the stereotypes not-white gathers in) is what she had better not be. Even in an allegedly postmodern era, the not-white woman as well as the not-white man are symbolically and even theoretically excluded from sexual difference. Their function continues to be, by their chiaroscuro, to cast the difference of white men and white women into sharper relief.

A kaleidoscope of not-white females, Asian, Native American, Latina, and African, have played distinct parts in the West’s theater of sexual hierarchy. But it is the African female who, by virtue of color and feature and the extreme metaphors of enslavement, is at the outermost reaches of “otherness.” Thus she subsumes all the roles of the not-white body.

The smiling, bare-breasted African maid, pictured so often in Victorian travel books and National Geographic magazine, got something more than a change of climate and scenery when she came here.

Sylvia Arden Boone, in her book Radiance from the Waters (1986), on the physical and metaphysical aspects of Mende feminine beauty, says of contemporary Mende: “Mende girls go topless in the village and farmhouse. Even in urban areas, girls are bare-breasted in the house: schoolgirls take off their dresses when they come home, and boarding students are most comfortable around the dormitories wearing only a wrapped skirt.”

What happened to the girl who was abducted from her village, then shipped here in chains? What happened to her descendents? Male-fantasy images on rap videos to the contrary, as a swimmer, in communal showers at public pools around the country, I have witnessed black girls and women of all classes showering and shampooing with their bathing suits on, while beside them their white sisters stand unabashedly stripped. Perhaps the progeny of that African maiden feel they must still protect themselves from the centuries-long assault that characterizes them, in the words of the New York Times ad placed by a group of African American women to protest the Clarence Thomas–Anita Hill hearings, as “immoral, insatiable, perverse; the initiators in all sexual contacts—abusive or otherwise.”

Perhaps they have internalized and are cooperating with the West’s construction of not-white women as not-to-be-seen. How could they/we not be affected by that lingering structure of invisibility, enacted in the myriad codicils of daily life and still enforced by the images of both popular and high culture? How not get the message of what Judith Wilson calls “the legions of black servants who loom in the shadows of European and European-American aristocratic portraiture,” of whom Laura, the professional model that Edouard Manet used for Olympia’s maid, is in an odd way only the most famous example? Forget “tonal contrast.” We know what she is meant for: she is Jezebel and Mammy, prostitute and female eunuch, the two-in-one. When we’re through with her inexhaustibly comforting breast, we can use her ceaselessly open cunt. And best of all, she is not a real person, only a robotic servant who is not permitted to make us feel guilty, to accuse us as does the slave in Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987). After she escapes from the room where she was imprisoned by a father and son, that outraged woman says: “You couldn’t think up what them two done to me.” Olympia’s maid, like all the other “peripheral Negroes,” is a robot conveniently made to disappear into the background drapery.

To repeat: castrata and whore, not madonna and whore. Laura’s place is outside what can be conceived of as woman. She is the chaos that must be excised, and it is her excision that stabilizes the West’s construct of the female body, for the “femininity” of the white female body is ensured by assigning the not-white to a chaos safely removed from sight. Thus only the white body remains as the object of a voyeuristic, fetishizing male gaze. The not-white body has been made opaque by a blank stare, misperceived in the nether regions of TV.

It comes as no surprise, then, that the imagery of white female artists, including that of the feminist avant-garde, should surround the not-white female body with its own brand of erasure. Much work has been done by black feminist cultural critics (Hazel Carby and bell hooks come immediately to mind) that examines two successive white women’s movements, built on the successes of two black revolutions, which clearly shows white women’s inability to surrender white skin privilege even to form basic alliances. But more than politics is at stake. A major structure o psychic definition would appear threatened were white women to acknowledge and embrace the sexuality of their not-white “others.” How else explain the treatment by that women’s movement icon, Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party (1973-78) of Sojourner Truth, the lone black guest at the table? When thirty-six of thirty-nine places are set with versions of Chicago’s famous “vagina” and recognizable slits have been given to such sex bombs as Queen Elizabeth I, Emily Dickinson, and Susan B. Anthony, what is one to think when Truth, the mother of four, receives the only plate inscribed with a face? Certainly Hortense Spillers is justified in stating that “the excision of the genitalia here is a symbolic castration. By effacing the genitals, Chicago not only abrogates the disturbing sexuality of her subject, but also hopes to suggest that her sexual being did not exist to be denied in the first place.”

And yet Michele Wallace is right to say, even as she laments further instances of the disempowerment of not-white women in her essay on Privilege (1990), Yvonne Rainer’s latest film, that the left-feminist avant-garde, “in foregrounding a political discourse on art and culture,” has fostered a climate that makes it “hypothetically possible to publicly review and interrogate that very history of exclusion and racism.”

What alternative is there really—in creating a world sensitive to difference, a world where margins can become centers—to a cooperative effort between white women and women and men of color? But cooperation is predicated on sensitivity to differences among ourselves. As Nancy Hartsock has said, “We need to dissolve the false ‘we’ into its true multiplicity.” We must be willing to hear each other and to call each other by our “true-true name.”

To name ourselves rather than be named we must first see ourselves. For some of us this will not be easy. So long unmirrored in our true selves, we may have forgotten how we look. Nevertheless, we can’t theorize in a void, we must have evidence. And we—I speak only for black women here—have barely begun to articulate our life experience. The heroic recuperative effort by our fiction and nonfiction writers sometimes feel stuck at the moment before the Emancipation Proclamation. It is slow and it is painful. For at the end of every path we take, we find a body that is always already colonized. A body that has been raped, maimed, murdered—that is what we must give a healthy present ( … )

The Presence that Signals an Absence, 1993

“On being the presence that signals an absence,” Essay in unpublished, photocopied catalogue for Coming to Power: 25 Years of Sexually X-plicit Art by Women. Curated by Ellen Cantor. Presented by David Zwirner Gallery and Simon Watson/The Contemporary, New York, NY, 1993.

© Lorraine O’Grady, 1993

O’Grady’s catalogue essay examined the nature of her inclusion in the 1993 Coming to Power show and responses to the exhibited diptych The Clearing, created two years previously.

****

“I don’t like it,” he says. “That’s not the way sex is supposed to be.”

He points at “Love in Black and White,” the right panel of a photo-diptych I call The Clearing.

But it is, I think. And it has been, often, for 500 years. I follow his finger and look at the white chevalier in tattered chainmail with a skull instead of a head. The knight’s hand proprietarily grasps the breast of an almost jet-black nude woman whose eyes look out beyond the frame and reflect centuries of knowing blankness and boredom.

“It doesn’t feel like that to me,” he says. This southern white curator is not going to take my diptych for his show. But his presence in my studio is proof of how far he and we have come.

Then he asks, “Are the two panels Before and After?”

He catches me off-guard, and my response is oddly diffident. Now I look at “Green Love,” the left panel, the one he’s said he likes. A nude white male and black female are floating on air, coupling ecstatically above the trees. Below them, on the grass, two mixed-raced children are playing tag while a gun, camouflaged on the lover’s discarded clothes, silently threatens the scene.

“No,” I say. “They’re Both/And.”

The curator gazes at me with an uncomprehending expression. Uncertainty is making me feel stupid. I know that when he leaves I will be able to construct an explanation. This is what I get for wanting images to take me someplace I cannot arrive with words. And yet the wordsmith in me wants to be defeated.

( . . . ) When I am asked to be on a College Art Association panel on the nude, I accept. It scarcely bothers me that it will be another of those “fly in the buttermilk” situations. I am hoping that, in some way I can’t yet foresee, my presence, my divergence from the panel’s premises, will not just add to, but alter the debate’s basic nature.

Another sign. I ask other artists and critics if they know of black women with bodies of work on the nude (I need more slides for my talk) and am taken aback. The only name I come up with is that of my friend Sandra Payne. Now I have to research in earnest.

As I work on “Olympia’s Maid,” my paper for the panel, I learn that during the two centuries of black fine art dating back to before 1960, the nude, Western art’s favored category, was avoided even by male black artists, with Eldzier Cortor’s Sea Island series of the 1940s a rule-proving exception. Since then, there have been individual pieces and a few series, but no oeuvres; and female black artists are vastly underrepresented ( . . . )

In the ’90s, I think, surely things have changed. When I learn that a young white woman artist named Ellen Cantor is curating a show called Coming to Power: 25 Years of Sexually X-plicit Art by Women, I want to know if her research will have results different from mine. ”

There isn’t much fine art, but there is video and film, most of it by younger black lesbians,” she says and adds more issues to my list of answer-questions. ( . . . )

I have not learned anything to make me stop being concerned and curious about the status of the black female body. It seems as beleaguered today as it has ever been. After a recent remark in Women’s Wear Daily that haute couture shows had begun to look like 125th Street, the black woman has almost disappeared from the fashion runway. And on rap videos, the few girl rappers are still heavily outnumbered by the girls shaking their booties, who are abused equally by the gangsta lyrics and the camera.

I have been writing this [catalogue essay] before Coming to Power opens. My diptych The Clearing is down at the gallery, the only piece by a black fine artist, and I am nervous. How will it work, I wonder? It is hardly a “representative” piece: its oblique historic references are simply to one way sex can be. But I am hoping the show’s context will stretch the definitions of nudity and sex in more than one direction, nudge them past the way sex is supposed to be.

At the opening, only “Green Love,” the left panel with the nude white male and black female coupling above the trees, is on the wall. The right panel, “Love in Black and White,” the one with the white male in tatty chainmail and the black female looking bored as her breast is grabbed, is returned to me. There just wasn’t room for it with so many pieces in the show, Cantor explains. At least she doesn’t say, “That’s not the way sex is supposed to be.”

The New Inquiry, 2016

Aria Dean, “Closing the Loop.” thenewinquiry.com, March 1, 2016.

Dean’s feature essay, contrasting white “selfie” feminism’s understanding of the body to that of contemporary

****

. . . . Intuitively, the selfie still feels valuable, but the compounded male, white, and colonialist gazes that work so hard to blur Black women and femmes into oblivion have too much force behind them to leave me with enough agency both to politicize a topless mirror selfie and to believe in that politicization one-hundred percent. Since it has been made abundantly clear, of late, that photo or video documentation proves very little and changes even less, simply documenting the Black female body falls short. Maybe a selfie comes close to proving that you exist – that you are at least firmly situated in time and space — but it proves nothing else conclusive about you: this is to say that, self-documentation of Black life still seems unable to contend with the “mass of images” produced by anti-blackness’s aggressive and distributed media campaign.

Merely presenting an image of a Black woman, no matter how affirmative and positive that image is intended to be, might still serve to reproduce an imbalance in agency. Last year’s abuses of Nicki Minaj’s wax figurine at Madame Tussaud’s are a charming offline reminder of this. Sure, we can all join in celebrating Nicki, but let us not forget that she is a body, she is flesh, and she is yours to possess. Or as Rozsa Farkas noted in “Whose Bodies 2,” “there are hierarchies that are afforded to certain (female) bodies, degrees of agency in one’s self-representation.” Her words call to mind a statement from early Black feminist

activist Anna Cooper: “the white woman [can] at least plead her own emancipation.” The black woman, on the other hand, has largely been expected to bear the multiple scars of racism and misogyny — misogynoir — in silence. And among these scars is an objectification that surpasses the image of the body, treading over it and into the realm of sheer, unprotected flesh.

THE Internet already flattens subjectivities into networks of branded associations and metadata. Mental and social operations are concretized and subjects are made objects in a platform-based social world. In this schema, it is perhaps inadvisable for those of us whose subjectivities have not yet been recognized on a large scale to objectify ourselves further using the tools vetted by those who perpetuate our oppression to begin with — even in efforts toward documenting one’s life with the hope of subverting external expectations.And anyway, on the Internet, this subversion is hardly revolutionary work. In fact, the algorithm thanks you for your contribution.

I don’t intend to advocate for a politic of anti-representation or a fundamental refusal of the image. However, being of the mind that to be Black in particular is to be at once surveilled and in the shadows, hypervisible and invisible, an either/or theory of representation seems unhelpful. So long as the feminist politic with the most traction enjoys this uncomplicated relationship to visibility, it will only sink further into aestheticization and depoliticization. As long as its framework is derived primarily from its racist, classist, capitalist “lean-in” equality-core (#freethenipple) predecessor, we – specifically Black women, but also perhaps all of us here whose bodies and selves are failed by a second-wave capitalist, classist, racist, cissexist, ableist feminism — do ourselves a disservice by considering it in the least bit viable.

Rather, we must devise a new politic of looking and being looked at. At the risk of sounding instrumentalizing, something like the Du Boisian double consciousness that has characterized Black life for centuries has wriggled its way into the minds of all subjects and now every single networked human being now exists under this condition of “looking at oneself through the eyes of others” or living, watching, being watched, watching yourself watch others. What could be a workable theory of auto-expression that takes into account the temporally, spatially, experientially flattened act of looking and being looked at? We are each the constant voyeuristic subject and object, both surveilled and surveyor. Devising a theory, politic, praxis (or whatever) that finds its center in the experiences of the Black femme and female body — perhaps historically the blurriest situation one can imagine for a body — might lead us to a theory, politic, praxis (or whatever) that speaks more accurately to the increasingly alienated experiences of all users – in particular those whose gender expressions fall outside of white cis-masculinity. Or as O’Grady writes, “if the female body in the West is obverse and reverse, it will not be seen in its integrity—neither side will know itself—until the not-white body has mirrored herself fully.”

DURING the process of writing this I came across images from Adrian Piper’s Food for the Spirit.The photographs document a ‘private performance’ where Piper fasted and read Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason in her NYC loft for an extended period. I tried and tried to make this work the centerpiece of this writing. It felt forced; I generally hate a cheeky art historical retrieval to begin with. However, Piper’s work still leaves me with a deep feeling of its value and its presence is instructive in this attempt toward understanding things a little better. . . .

Andil Gosine On New Worlds (BG), 2012

Andil Gosine, “Lorraine O’Grady’s NEW WORLDS.” Unpublished 1500-word article.

Though still unpublished at the time of the 2012 “New Worlds” show, this incisive essay by Gosine, a York University (Toronto) professor who’d written earlier on hybridity in O’Grady’s work, has since been published in the brochure for O’Grady’s solo show at Harvard University’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts (“When Margins Become Centers,” 2015), and, accompanied by Spanish translation, in the catalogue for her survey show at the Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo, Seville, Spain (“Lorraine O’Grady: Initial Reognition,” 2016). Gosine’s essay is the most complex and complete discussion of the interconnections between the video and the photomontages in the New Worlds installation to date..

****

Gently trembling quivers of hair provide a perfectly pitched and suitably gorgeous meditation on a conversation Lorraine O’Grady started twenty years ago. The artist’s conundrum then, as now, was herself and us. As she wrote on the wall of the 1991 New York exhibit in which the images first appeared: What should we do? What is there time for? What should we do with the mess of desires, identities and culture that mixing, both forced and free, has unleashed in the Americas since colonial encounter?

Her reply in that first solo show at the INTAR Hispanic American Arts Centre opened with two works from her series Body Is The Ground of My Experience (BodyGround): the delicate Fir-Palm, a black-and-white photomontage featuring a hybrid New England fir and Caribbean palm growing from a black woman’s torso, and The Clearing, a photomontage diptych showing conflicting scenes of interracial sex played out in black-and-white against the backdrop of a forest clearing. Twenty years later, for her 2012 solo show New Worlds at Alexander Gray Associates, the two are paired with her newest work, Landscape, Western Hemisphere, a mesmerizing eighteen-minute black and white wall-sized video projection that features those compelling soft and sharp movements of her hair.

The appropriately titled New Worlds is O’Grady’s tome on five hundred years of history. It offers further evidence of the artist’s prescience. A complex, subversive thinker, once overlooked, she has always made work that demands committed attention–no easy feat in any situation but especially difficult in an earlier, racially segregated art world that could not find place for her. The Fir-Palm establishes a context for one strand of a lifelong interrogation that has consumed her practice, revealing the tensions surrounding the artist’s identity and her production of body and desire as foundational for the development of the Western Hemisphere. Its botanic concoction embodies O’Grady’s heritage as the child of Caribbean immigrants who left Jamaica for Boston at the dawn of the twentieth century. The image is at once an assertive claim about her own hybridity and, through the clouds hovering in its background, an acknowledgment of its precarious condition. The Fir-Palm puts to picture Homi Bhabha’s “Third Space”; through O’Grady, Gayatri Spivak’s subaltern speaks.

If The Fir-Palm signposts hybridity, The Clearing is its visceral elaboration. In it, O’Grady’s arguments are teased out, beginning with the diptych’s subtitle: “or Cortez and La Malinche, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, N. and Me.” The imbrications of identity and culture with nature and sexuality are demonstrated in the scenes’ activities. In the left panel, a black woman and white man appear elevated in clouds, their expressions matching the ecstasy of their sexual engagement. Below, children are playing in the clearing, as a pile of the couple’s discarded clothes topped by a gun lies, carelessly, on the ground. There are no children in the image on the right. The black woman’s stiff corpse stretches out on the ground, while the white man, now wearing a skull as his head and robed in a chainmail vest, hangs over her.

( . . . ) The black-white union represented in the image is both dream and nightmare, neither a choice between them nor one ending with death, but a site of continuous tension. The sexual desires underpinning this engagement are fuelled through and through by colonial fantasies of “race.” Yet they also potentially facilitate the destabilization of the structuring essentialism that underpins colonial acts of violence. The personal experiences that drive O’Grady’s imagination and the production of The Clearing serve as testimony to the complicated experience of the colonial subject—to its simultaneous experience of violence with desire, of pain and punishment with dreaming and longing—and of the impossibility of resolution. The Clearing insists on a complicated reading of cultural hybridity, one that claims neither celebration or denunciation, but rather appreciates its simultaneous and inseparable brutalities and pleasures. The images comprising the diptych are not an ’either/or’ proposal but a ’both/and’ description of what is left in the aftermath of colonial encounter.

The Clearing is especially concerned with the interracial pairing it puts to picture, of the black woman and white man. In “Olympia’s Maid,” O’Grady theorized that the relationship between the white male and black female broke the “faith” between the white male and white female. It marked, she says, “the end of courtly love,” represented in The Clearing by the man’s chainmail shirt. The three relationships named in the sub-title situate this sexual pairing as central to the development of the Western Hemisphere. None are simply innocent representations of romantic love, nor are they simply condemnable in the terms of political morality. ( . . . )

Bennett Simpson (BG), 2012

Bennett Simpson, editor, Blues for Smoke, pp 13-14, 166-169 and pp 23-25, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and Delmonico Books/Prestel, Munich, London, New York, 2012.

In a catalogue with the improvisational quality of the music, the final section of Blues for Smoke curator Simpson’s essay “This Air” is titled “The Clearing,” from a piece by O’Grady of that name in the exhibit, and discusses how the piece echoes the show’s themes.

****

The Clearing

In her collaged photo-diptych Body Ground (The Clearing: Or Cortez and La Malinche, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemmings, N. and Me) (1991/2012), Lorraine O’Grady insists upon, rather than running from, the profound racial and sexual collisions that have shaped America from its origins. An allegory of miscegenation spanning multiple eras—from the colonial past to the contemporary present—the work depicts a trio of mixed-race couples set amidst a primeval forest clearing. On the right, a white male skeleton clad in conquistador chain mail appears to grope the naked breast of a black female figure, whose listless face turns toward the viewer. In the panel to the left, two children chase a ball toward a pile of discarded clothes (barely concealing a gun), their youth perhaps representing the early nation of Jefferson and Hemmings, while hovering in the sky overhead a white man and a black woman embrace in what appears to be reciprocal copulation. Taken together, the couples reflect the deep intermingling of pain, pleasure, abuse, and desire that gave birth to and continues to inform the peculiar hybridity of the New World. O’Grady’s metaphors of complexity and “clearing” are not mutually exclusive, but dependent, the latter, really, an avowal of recognition, truth-telling, and vision that might cut through or open up the various tangles of prejudice that keep something like “America” in denial about its mixed identity. As the artist states:

My attitude about hybridity is that it is essential to understanding what is happening here. People’s reluctance to acknowledge it is part of the problem… The argument for embracing the Other is more realistic than what is usually argued for, which is an idealistic and almost romantic maintenance of difference. But I don’t mean interracial sex literally. I’m really advocating for the kind of miscegenated thinking that’s needed to deal with what we’ve already created here.4

“Blues for Smoke” is likewise motivated by some basic desire to create space—to find a clearing—so that the complexity of “what we’ve already created,” our lived experience of culture and identity, might come into sharper relief. On one level, this desire can be sensed in the multiplicity of artists and artworks collected in the exhibition: in the presence of white artists placed in relation to black cultural contexts, in a framing of the blues to include questions of sexual and gender identity, and in the juxtaposition of historical tendencies that would seem “not to fit” with each other. ( . . . )

Artnet (BG), 2012

Emily Nathan, Lorraine O’Grady: New Worlds.” ArtNet.com, NYC Gallery Shows, THE NEW YORK LIST, Apr 27, 2012.

Analysis of New Worlds focusing on how the works’ resistance of “easy classification” and their straddling of “artificial divides of genre and type” serve to replicate O’Grady’s thoughts on the contemporary world, one “shaped and inflected by miscegenation.”

****

For her second show at Alexander Gray Associates, the legendary feminist performance artist and photographer Lorraine O’Grady (b. 1934), who trained in economics and worked for years as a rock journalist, focuses on the idea of the hybrid – cultural, theoretical, biological. Taken together, the three works included in the show, a 19-minute film and two photomontages from the artist’s iconic “Body Language” [sic] series, initiated in 1991 and re-formatted this year, seem to insist that our contemporary world is shaped and inflected by miscegenation far more powerfully than we might like to acknowledge.

To that end, each work straddles artificial divides of genre and type and resists easy categorization. In The Fir Palm, a literally hybridized tree – part Caribbean palm, part New England fir – emerges from a smooth black ground against a could-roiled sky. The photomontage looks like a landscape, until you detect the sinuous, sensual curves of a black female torso where you thought you saw only earth. In the photo-diptych The Clearing, whose composition is inspired by Manet’s Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe, an interracial couple makes love outside in one panel, elevated above the ground by ecstasy, and lies together awkwardly in the other, the female vacant and resigned, the male aggressive, masked by a skull and draped in chain-mail. Both scenes seem to give some account of colonial history, and each is equally dubious. ( . . . )

Beyond/In Western New York, 2010

Carolyn Tennant, Beyond/In Western New York: Alternating Currents “Lorraine O’Grady.” Wall Text for O’Grady’s Buffalo Biennial installation at the Anderson Gallery, University at Buffalo, 2010.

Tennant’s wall text connects two complementary pieces, O’Grady’s 1991 photomontage diptych The Clearing, and her later video Landscape (Western Hemisphere), 2010, via the concept of the bridge, referencing both the musical term and a frequently quoted phrase from O’Grady’s writing.

****

“Wherever I stand, I find I have to build a bridge to some other place.” Lorraine O’Grady

By presenting a video installation newly created for Beyond/In Western New York with a twenty-year-old photomontage diptych, Lorraine O’Grady creates a bridge for herself and for viewers, not simply to link two works but as a strategy that (re)engages with each work’s concepts. In music, the bridge serves as a section in the score that, in contrast with the chorus and the verse, prepares the listener for the approaching climax. Her new video Landscape (Western Hemisphere) responds to The Clearing (1991), a work that has not been recuperated by scholars and curators as have many of O’Grady’s other radical works, so as to encourage reconsideration of the earlier work. The new video emerged from a recent dialog with York University Associate Professor Andil Gosine, in which the artist spoke of her artistic intentions for The Clearing and described the work’s original reception, one of silencing and censure. The surrealistic photomontage depicts what filmmaker John Waters calls “the last taboo”: black and white sexual unions which O’Grady depicts as both born from desire and in service to power.

Landscape (Western Hemisphere) presents The Body as a landscape, harmoniously addressing many of the conceptual themes of the original diptych, later re-titled by the artist as The Clearing: or Cortez and La Malinche, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, N. and Me. When the two works are presented together, a new space is created—one where intertextuality and intersubjectivity can coexist. Just as the distinct panels of the diptych both function in contrast yet are seen together, the video and the diptych forge a “space between,” allowing the viewer greater access to the silenced work. O’Grady takes us to the bridge.

Buffalo Biennial, 2010

Carolyn Tennant, “Lorraine O’Grady.” Beyond/In Western New York: Alternating Currents, pp. 114-115, Buffalo Fine Arts Academy, 2010.

Catalogue essay for Beyond/In Western New York, the Buffalo biennial, on O’Grady’s two-part exhibit: her photomontage diptych The Clearing: or Cortez and La Malinche, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, N. and Me, 1991, and a new video made to complement it: Landscape (Western Hemisphere), 2010.

****

LORRAINE O’GRADY

American, b. 1934 / Lives and works in New York, NY

Not long after her diptych The Clearing, 1991, appeared as part of her first solo exhibition, Lorraine O’Grady expanded the work’s title as a way to explicate its meaning. Unlike other work featured in BodyGround, an installation of photomontages, this piece encountered a particularly negative reaction. In this investigation of interracial relationships, the artist uses the visual language of Surrealism to represent the white male/black female union. With its concurrent display of eroticism and domination, the work exposed enduring cultural anxieties. Most disturbing, however, was the resistance of some audiences to engage with the work at all. There was no debate about the work’s aesthetic or conceptual basis; instead, those who might participate in such a dialogue ignored it completely, censoring what proved too provocative. Dismissing the diptych was an attempt to silence it, but when O’Grady renamed The Clearing, she began a process of recuperation. Expanding the title to The Clearing: or Cortez and La Malinche, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, N. and Me, the artist reveals her place in a larger historic trajectory: as both an African Caribbean American with an inherited bicultural background, and as an active participant in interracial relationships.

The Clearing… demonstrates how the diptych, as a formal device and a conceptual tool, serves a strategic function in O’Grady’s work. The left panel presents a naked couple in an ecstatic embrace, floating in the sky, hovering above the trees; on the ground below, a young boy and girl—the offspring of this union—run after a ball as it rolls towards a pile of the adults’ discarded clothing, amongst which a handgun is seen. The right panel portrays a man and a woman on the ground in the same landscape, however, their bodies are arranged in a sinister pose. Clothed in chain mail, a skull replacing his face, the white man leans dominantly over the black woman’s naked body and fondles her breast. Her face is turned away, her arms stiff at her sides, her eyes fixed on the sky above. Rather than an attempt to negotiate different points of view, O’Grady uses the diptych to contain opposing forces. Once the “either/or” fallacy is revealed, the artist can reframe binary oppositions as “both/and.” In this way, O’Grady’s work dismantles Western dualism and those false dichotomies that sustain systems of power.

Two decades later, O’Grady continues an ongoing process of recuperation. Even as a bicultural President sits in the White House, The Clearing… remains radical, perhaps, the artist suggests, because the work has not been “de-fanged.” “Silencing is a process that needs to be constantly reinforced, but un-silencing also needs to be reinforced.” Her latest efforts involve the introduction of a new panel, a time-based video installation that she now considers part of the diptych. Like the expanded title, the video provides yet another way to reclaim subjectivity. Working with one of her most striking characteristics, her curly mane, as a metaphor, O’Grady opens the work up to new contemporary meanings; for those with multi-ethnic backgrounds, hair has provided evidence of one’s background long before its use in DNA testing. By including a sound collage composed from a dialogue about the work and her experiences as an artist, as a woman, and as a multi-ethnic artist, O’Grady, quite literally, gives it voice and breaks a decades-old silence.

Since her earliest interventions, O’Grady’s art has served as institutional critique. “The black female’s body needs less to be rescued from the masculine ‘gaze’ than to be sprung from a historic script surrounding her with signification while at the same time, and not paradoxically, it erases her completely,” she wrote in a postscript to her widely anthologized article “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity.” Visualizing what once was only recognized through its absence, she reminds audiences that invisibility and silencing is not simply an art-historical problem, but a continuing crisis in contemporary art.

Kymberly N. Pinder, 2000

Kymberly N. Pinder, “Biraciality and Nationhood in Lorraine O’Grady’s ‘The Clearing: or Cortez and La Malinche, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, N. and Me.” Paper for the “La Malinche as Metaphor” panel of the College Art Association Conference, 2000.

An article on work by artists responding to racial hybridity that features a discussion of O’Grady’s diptych, The Clearing. Published in Third Text: Critical Perspectives on Art and Culture 53, Winter 2000-01.

****

For when we swallow Tiger Woods, the yellow-black-red-white man, we swallow something much more significant than Jordan or Charles Barkley. We swallow hope in the American experiment, in the pell-mell jumbling of genes. We swallow the belief that the face of the future is not necessarily a bitter or bewildered face, that it might even, one day, be something like Tiger Wood’s face: handsome and smiling and ready to kick all comers’ asses.

The hope in ‘the yellow-black-red-white man’, reflected in the Tigermania that swept the US in the mid-1990s, is indicative of the racial crossroads at which the US, as a nation, finds itself at the close of the twentieth century. . . . Where are we as a nation regarding race when Woods can consider himself ‘Cablinasian’ while some southern states are still officially ending their ‘one-drop’ rules and [taking] laws against mixed marriages off the books? How can we address the concerns of those who see Affirmative Action as all but dead?

Some contemporary artists in the US have been struggling with these issues during the 1980s and 1990s. Lorraine O’Grady is one of them. She originally titled her photomontage diptych The Clearing in 1991, however, later, she lengthened the title to The Clearing: or Cortez and La Malinche, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, N and Me to clarify the historical and personal relevance of the work. The left half of the piece presents the relationship between the black woman and white man as loving while the right as malevolent. The skeletal face of the man and the gun in the pile of clothing provide elements of violence and death. Yet O’Grady says, ‘it isn’t a “before/after” piece; it’s a “both/and” piece. This couple is on the wall in the simultaneous extremes of ecstasy and exploitation.’ The complex relationship between exploitation and defiance for such ‘women of color’ as La Malinche and Sally Hemings has become a trope of American hybridity and assimilation.

. . . .

[Figures] such as Malinche and Pocahontas have also gained political significance as they are seen to offer hopeful moments of cross-cultural co-operation in our racially divided pasts. For example, the 1995 Disney film about the latter presents the saga as a love story in which Pocahontas risks her own life to save that of John Smith. This narrative, based upon Smith’s account and revised for a young audience, excludes Matoaka’s (Pocahontas’s real name) later kidnapping an forced conversion. Many applauded Disney’s politically correct inclusion of Native American history into its repertoire, however, the effects of the distortion of ‘Distory’ on our children’s understanding of national history and race relations are questionable. The scale of this type of nationalistic desire for harmony, past and present, through these icons, is summed up in the words of Woods’s father, Earl:

Tiger will do more than any other man in history to change the course of humanity. . . Because he’s qualified through his ethnicity to accomplish miracles. He’s a bridge between East and West. There is no limit because he has the guidance. . . He is the Chosen One. He’ll have the power to impact nations. Not people. Nations.

O’Grady’s photomontage parallels the relationships of La Malinche and Sally Hemings. La Malinche’s facility at languages made her translator for the Spanish conqueror Hernan Cortez; then she gave birth to a racial bridge, their son, the original mestizo. La Malinche’s other name was La Lengua, the language, and the transformation from ’race traitor’, La Malinche is a slur in some Mexican dialects, to the status of the great communicator an reconciler, as she has been recently reclaimed, namely by feminists, is a leitmotif in the biographies of such historical figures. No matter her intentions, La Lengua brought together Europeans and Indians; Hemings united, inside and outside of herself, Africans and Europeans; and Woods, the ‘yellow-red-black-white man’ brings together all of the ‘primary races’ in one body. As his mother Tida says, ‘Tiger has Thai, African, Chinese, American Indian and European blood; he can hold everyone together; he is the Universal Child.’( … )

Michele Wallace, 1994

Michele Wallace, “Black Female Spectatorship and the Dilemma of Tokenism.” Generations: Academic Feminists in Dialogue, pp 88-101, University of Minnesota Press, 1997.

An article in dialogue with O’Grady’s “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity.” In Generations: Academic Feminists in Dialogue, Devoney Looser and E. Ann Kaplan, eds. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 1997. pp 88-101.

****

( . . . ) In this regard, I would like to pose a further question: what if the black female subject is constructed much like the white female subject? Or what if the similarities between the psychoanalytic construction of the black female subject and that of the white female subject are greater than the dissimilarities? Moreover, if you accept the thesis that psychoanalytic film criticism proposes of a closed Eurocentric circuit in Hollywood cinema in which a white male-dominated “gaze” is on one end an the white female “image” is on the other end, what happens to the so-called black female subject? Does she even exist? And if she does, how does she come into existence?

Helpful to me in thinking about the problems suggested here has been the writing of black female conceptual artist and theorist Lorraine O’Grady in “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity” and in her unpublished “Postscript,” and the writing of black feminist art historian Judith Wilson in “Getting Down to Get Over: Romare Bearden’s Use of Pornography and the Problem of the Black Female Body in Afro-U.S. Art.” In looking at the status of the black female nude in art history, which is handled very differently from the white female nude, O’Grady insists that the only constant in Euro-American theoretical analysis has been “the black body’s location at the extreme,” whereas Wilson remarks on how black fine artists have also avoided the black female nude because of its negative associations, perhaps with the sexual exploitation of slavery.

O’Grady, who says her goal is to “deal with what Gayatri Spivak has called the ‘winning back of the position of the questioning subject’” is thus prompted to suggest that “the black female’s body needed less to be rescued from the masculine gaze than it had to be sprung from an historic script surrounding her with signification while at the same time, and not paradoxically, erasing her completely.” While I think that O’Grady is onto something here when she suggests that the issue for black women is one of establishing subjectivity, I haven’t always been able to see the notion of a black female subject as separate from the notion of a white female subject. Would this mean, after all, that there were Asian, Indian, and African female subjects as well? Is subjectivity really divided by race, nationality, ethnicity? I don’t think so. I’m not saying that subjectivity isn’t divided. I think it probably is divided in some manner, but I’m not sure that it can therefore be viewed as historically and materially specific, and that it divides easily by ethnicity, nationality, or any other constructed or natural rubric. Certainly, “spectatorship” as it is constructed by the dominant discourse does not.

On the other hand, things like class allegiances and identity, sexuality, and experience seem to make a profound difference in how the female subject is constituted visually and how those images circulate. Even more significant here is O’Grady’s suggestion that the status of the white female “image,” or the objectification of the white female body, is part of the circuit of subjectivity for women. In other words, although the white male “gaze” (or the gaze of the dominant culture) objectifies and, therefore, dehumanizes the white woman, in fact, that objectification also implicitly verifies the crucial role white women play in the process of or circuit of spectatorship. In other words, the process of objectification also inadvertently humanizes as well a built-in advantage that is then denied to women of color in general, but to the despised (or desired) black woman in particular.

So the problem of white female subjectivity is one of reversing the terms somehow, or reversing the connection or the hierarchy between male and female, whereas in the case of the black female body, or the body of the other, the connection is to a third, much less explored level in the hierarchy, the sphere of the abject, which includes, as Sander Gilman and Michel Foucault have pointed out, the pathological.

As such, reversal is no cure and cannot take place. Black female subjectivity remains unimaginable in the realm of the symbolic. O’Grady’s approach as an artist seems to be to attempt to upgrade the status of the black female nude, or at least to get us to think about how and why the black female nude is devalued. Can you imagine Louise Beavers in a sexy dress in Imitation of Life? And yet Bessie Smith played just such a role in Saint Louis Blues, not to mention in life.

Lately, I have been working on my mother Faith Ringgold’s series of story quilts. The French Collection, in which she illustrates the adventures of a protagonist named Willa Marie, born in 1903, who goes to Paris to become an artist and who alternates working as an artist’s model with her own painting (true of many female artists). In the process, the subsequent images toy with this circuit of subjectivity that O’Grady proposes as so crucial, for Willa Marie is configures as both subject and object by the text and the images.

In a multicultural context, the response of many is to historicize the question of subjectivity (which I believe is crucial as well) and, in the process, dispense with the synchronic explanations of psychoanalytic complexity and abstraction. But, then, how do we account for the play of the unconscious in black cultural production and in the everyday lives of black people? The play of the unconscious roughly refers to the highly ambivalent relation of plans to practice, and stated intentions to unconscious motivations, in African American cultural and social life.

I ask the question about the unconscious precisely because of the problem of interpreting the sexual and gender politics of recent mainstream black cinema. Clearly, the construction of spectatorship in Malcolm X cannot be wholly explained by relying on empirical data. We can guess that the construction of gender and sexuality in Spike Lee’s Malcolm X has more to do with Lee’s own issues around gender as well as cinematic traditions in the specularization of women’s bodies, and black women’s bodies, in Hollywood cinema than it has to do with Malcolm X’s life ( . . . )

Meanwhile, Daughters of the Dust, a film by independent black filmmaker Julie Dash, attempts to provide a corrective to the boyz. The film deliberately sets out to tackle the problem of upgrading the black female image and gets bogged down in excessive visuality. Yet again, something crucial has to be occurring on the level of “the hypothetical point of address of the film as a discourse.” After all, if it makes no difference how a film deploys its black bodies, why have they been so relentlessly excluded in the past? ( … )

Calvin Reid, 1993

Calvin Reid, “A West Indian Yankee in Queen Nefertiti’s Court,” New Observations #97: COLOR, pp, 5-9, September/October, 1993.

Article in New Observations #97: COLOR. September/October 1993, pp. 5-9. Special issue, edited by Adrian Piper.

****

( . . . ) After 1988 [O’Grady’s] interests have shifted [from performance] to creating fixed images within the gallery space. She has spoken of her performances as a heightened form of writing, a form that enables her to combine the linear narrative of the story with the ability to simultaneously present successive layers of fact and symbol. “Performance is the way I write most effectively,” she said in an unpublished interview with Tony Whitfield in 1983, “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire is actually a didactic essay written in space, while the form of Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline approximates that of a book — a family photo album, interlaced with personal reminiscence and ritual.”

The new work, photomontages dating from 1990, was displayed in 1991 at New York City’s INTAR Gallery. Despite her careful documentation of [the earlier] performances she has expressed some dismay at the transience aligned to physical performance — the inability of her audiences to savor, contemplate and engage the issues in a work that is suddenly here and just as quickly gone. These photo works represent another effort to “write” in an unconventional mode and the manipulation of composition and culturally charged imagery used to spur an interpretive response informed by O’Grady’s pervasive sense of cause, effect and social dilemma.

Once again O’Grady uses the pictorial works to inspect her own life while dissecting that around her. In these works, using a model and photographer for technical applications, O’Grady’s interest focuses often on the Black female body, highlighting its general absence from the contemporary visual discourse and arranging it in compositions of striking visuality, relocating her critical vantage point from real acts in real space to a postmodernist location as a creator and manipulator of images capable of mass projection.

In the 1991 work, The Fir Palm, a tellingly fictional “hybrid” stalk of vegetation — palm tree trunk topped with the bristled branches of the Northern Fir tree — appears to spring from the landscape of a close-up crop of the model’s loamy black body. Planted exactly in the navel, this absurd combination of geographical and arboreal opposites extends upwards towards a sky streaked with clouds. O’Grady’s West Indian background, symbolized by the trunk of an island palm tree, is visually married to an equally dear geographically resonant emblem of Yankee New England. Strangely captivating and mildly comic, the image manages to evoke the sublime contradictions that contribute to the artist’s sense of identity as well as what she sees as her cultural legacy as a Black artist and intellectual. Her refreshingly unconventional symbolism unites the apparently contradictory elements of her life and development. She presents her life — middle-class Black female and an intellectual to boot — as representative of a new wing to the African-American cultural diaspora; as a bonafide extension of traditional representations of Black culture as a southern American phenomena or as an urban extension of that tradition. Her work opens black tradition to a broad range of Black experience, chipping away at the tendency of Black folks as well as White folks to narrow Black experience.

In Lilith Sends Out the Destroyers, a kaleidoscopic stream of warships spouts upward and outward from the pubic area of another close-in profile shot of the Black female body. This image, rife with connotations of destructive progeny and latent female power, contrasts with other works chronicling interracial sexuality, death and domination, once again as strikingly enigmatic as they are culturally interrogative.

In The Clearing, 1991, (the work is composed of two individually titled and framed panels), she presents the perennially startling image of interracial lovemaking within a visual discourse on the nature of sexual relationships between Black women and White men. The effect of this work is a complex parade of imagery calculated in its attempt to visualize the female contemplation of interracial coupling; its precedents, its contradictions and to some extent its inevitability. In the panel on the left, subtitled Green Love, hovering in the sky above a lush park setting, a white man settles between the legs of his Black mate in an image of sexual partner and tenderness; while below, in a clearing, children play, running around a forgotten pile of clothing. The panel on the right, Love in Black and White, presents a White man covered in medieval chain mail, seducing a Black woman. A death’s head obscures the man’s features while his hand rests on the naked, impassive woman beneath. The image captures an image of white men, sheathed in social armor; protected and preying on a relationship of unequal power with the inherent potential for blatant sexual exploitation.

In Gaze 1,2,3,4, a series of portraits present two images of the four individuals pictured, two Black men and women, their torsos bare. A smaller image of each model, whose expressions are responses to cues from the artist, is placed over (or seemingly within) a larger image of the same individual. This simple but effective image presents two faces to the world; the inner and outer view, the physical and the metaphysical. The works attempt to locate the existential core of their subjects, stripped of defenses, presumptions and psychic bric-a-brac. The models stare directly at the viewer, locking their photographically portrayed sensibilities into the viewer’s.

Judith Wilson, 1992

Judith Wilson, “A Postmortem On Postmodernism?” Unpublished slide lecture for a panel of The American Photography Institute, New York University, NY. 1992.

Wilson’s lecture discusses black artists’, including O’Grady’s, ambivalence toward and ambiguous status within postmodernist discourse. Delivered just prior to O’Grady’s publication of “Olympia’s Maid,” her lecture tellingly inflects Thomas Feucht-Haviar’s later discussion of the O’Grady essay’s treatment of subjectivity as a critical category needed to oppose regimes of knowledge acquisition and production based in compromised forms of power relations.

****

Postmodernism has been especially problematic for artists of color, at the same time that it has gained them greater visibility than ever before. A few examples:

(SLIDE 1L, images and titles in slide list at end) Adrian Piper is one of the artists whom I have long considered a pioneer African-American post-modernist. Yet, Piper, a philosophy professor deeply enamoured of Kantian metaphysics, firmly rejects postmodernism’s anti-rationalist philosophical premises.

(SLIDE 1R) Similarly, but for quite different reasons, Carrie Mae Weems has taken me to task for characterizing her work as “postmodern.” To Weems, such labels smack of Eurocentrism. (SLIDE 2L) With Lorna Simpson, we have yet another wrinkle–an African-American photographer whose work gained immediate acceptance as “postmodern” by mainstream critics and curators, while the race and gender-specificity of her images, though frequently praised, went largely unexamined–except by critics of color, such as Kellie Jones, Yasmin Ramirez and Coco Fusco.

To the extent that postmodernism has been a privileged discourse within the artworld for the past decade or so, these artists’ ambivalence toward and their ambiguous status with respect to that discourse can be seen as the simple consequence of a long history of denial, insult and exclusion. In the tendency of someone like Piper to reject a theoretical program that celebrates difference and radically critiques the interface of political and cultural power, I am reminded of the self-defeating rigidity and caution that the legal scholar Patricia J. Williams has described in The Alchemy of Race and Rights. Contrasting her own behavior with that of a white colleague, Williams writes:

“Peter . . . appeared to be extremely self-conscious of his power potential . . . as white or male or lawyer authority figure. He therefore seemed to go to some lengths to overcome the wall that image might impose. The logical ways of establishing some measure of trust between strangers were an avoidance of power and a preference for informal processes generally.

On the other hand, I was raised to be acutely conscious of the likelihood that no matter what degree of professional I am, people will greet and dismiss my black femaleness as unreliable, untrustworthy, hostile, angry, powerless, irrational, and probably destitute. On the other hand, I was raised to be acutely conscious of the likelihood that no matter what degree of professional I am, people will greet and dismiss my black femaleness as unreliable, untrustworthy, hostile, angry, powerless, irrational, and probably destitute.”